Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

10 Exciting Developments Fusing Food And Real Estate

10 Exciting Developments Fusing Food And Real Estate

A new report, Cultivating Development, shows how culinary innovation and foodie culture can help build community

BY PATRICK SISSON NOV 29, 2016, 2:15PM EST

There’s no question that attitudes towards food and healthy living have evolved over the last few decades. Cuisine and food culture have undergone dramatic shifts, from the proliferation of celebrity chefs to ever-more sophisticated palettes; since 1994, the number of farmers markets in the country have increased fivefold. It only makes sense that developers, always on the lookout for the next standout residential and commercial development, would start factoring these trends into their new projects.

In a new report, Cultivating Development, the Urban Land Institute examines how the real estate industry has begun to embrace culinary sophistication and foodie culture, positioning shared gardens and upscale food halls as must-have amenities and retail anchors. These additions not only fuel commerce and community, but can lead to more sustainable, equitable development that legitimately improves the health of residents. Here are 10 of the projects highlighted in the report, from healthy residential developments to indoor farming centers, that both help the bottom line and add value to the community.

Refresh Project (New Orleans, Louisiana)

Turning a food desert into an oasis, this community development project located between the Treme and Mid-City neighborhoods goes beyond adding a healthy grocery option to assembling the resources for healthier lifestyles. Spearheaded by the local group Broad Community Connections, this developmet replaced a vacant supermarket with a Whole Foods Market and a variety of healthy nonprofits, such as the Tulane University Goldring Center for Culinary Medicine, a first-of-its-kind program that teaches healthy eating and cooking in a clinical setting, the ReFresh Community Farm, and Liberty’s Kitchen, an on-site food service and life skills training center. The project didn’t just encourage better eating habits, but offered more holistic health and wellness assistance as well as career opportunities.

Arbor House (Bronx, New York)

This new housing development seeks to provide not just affordable housing, but a healthy diet, to a community that’s been disproportionately affected by diabetes and heart disease. A 10,000-square-foot hydroponic rooftop farm atop the 124-unit property will grow fruits, vegetables, and herbs, which will then be sold in a neighborhood lacking a surfeit of healthy options.

The Pinehills (Plymouth, Massachusetts)

This new village center models itself after more a traditional layout and design, meaning extensive open space (only 30 percent of the land is developed) and a large two-acre village green as a centerpiece. The retail area, anchored by The Market, the state’s first “healthy market,” is linked to nearby homes via a network of walking paths.

Mariposa (Denver, Colorado)

Built by the city housing authority, this 800-unit mixed-income development utilizes clever design and an array of public programming to encourage healthy living, including a weekly farmer’s market, the on-site Osage Cafe, and a community bike-share program.

Mercado La Paloma (Los Angeles, California)

Established nearly 15 years ago, this former garment factory-turned-food industry incubator has been a celebrated success, earning plaudits from the U.S. Congress. Nearly 200 locals, from social service workers and artists to immigrant entrepreneurs, are employed at this complex, which helps provide startup capital, a health center, as well as conference rooms and performance spaces. An in-house initiative to provide nutrition information, La Salud Tiene Sabor, has spread to local restaurants and markets.

Summers Corner (Summerville, South Carolina)

A “community in a garden” near Charleston, this planned development includes a bike trail system, demonstration gardens, and an outdoor market. The main garden houses the Clemson University master gardener program, which gives residents the opportunity to sharped their skills in the company of experts. Produce from the garden are also used at the nearby Corner House cafe.

Aerofarms (Newark, New Jersey)

This recently opened indoor farm, set inside a former steel mill, will eventually grow two million pounds of produce annually, and serve as an anchor for the RBH Group’s Makers Village project, a three-acre sustainable production district set to activate the local job market.

Eco Modern Flats (Fayetteville, Arkansas)

Using healthy lifestyles as a selling point, a local developer turned these blocks of ‘60s-era apartments into greener, more sustainable homes, featuring a landscape redesigned to include native plants, rainwater harvesting, and rooftop gardens. Parking was also moved to help create a massive communal garden, one of many community features that helps build relationships among tenants.

Aria Denver (Denver, Colorado)

Set to open in 2018, this infill community on the site of a former convent will knit together 450 homes and a variety of gardening and health amenities, including a pay-what-you-can farm stand, a permaculture pocket gardens, a 1.25-acre production garden, shared kitchens, as well as access to healthy cooking classes. The developers believe “giving up” land for these amenities ends up raising the value of the project as a whole, both making it more attractive and bringing in more community partners.

Rancho Mission Viejo (Orange County, California)

A massive series of planned developments intertwined with farms and ranches, this residential and retail project offers a more sustainable and community-oriented model for homebuilding. The first village, Sendero, includes two communal farms amid 941 homes, and when finished, the entire development will include schools, parks, clubhouses, and other recreational facilities. .

Rising Need For Nursery, Indoor And Vertical Farming

There will be a new vertical agriculture revolution, because right now we use up a third of the usable land of the world to produce food, which is very inefficient. Instead we will grow food in a computerized vertical factory building (which is a more efficient use of real estate) controlled by artificial intelligence, which recycles all of the nutrients so there’s no environmental impact at all

Rising Need For Nursery, Indoor And Vertical Farming

by Frank Tobe

November 28, 2016

To meet rising food demands from a growing global population, over 250 million acres of arable land will be needed – about 20% more land than all of Brazil. Alternatively, agricultural production will need to be more productive and more sustainable using our present acreage. Meeting future needs requires investment in alternative practices such as urban and vertical farming as well as existing indoor and covered methods.

Ray Kurzweil, futurist, inventor and Google’s Director of Engineering, said in an interview in The Times in 2013:

There will be a new vertical agriculture revolution, because right now we use up a third of the usable land of the world to produce food, which is very inefficient. Instead we will grow food in a computerized vertical factory building (which is a more efficient use of real estate) controlled by artificial intelligence, which recycles all of the nutrients so there’s no environmental impact at all.

Fully automated regional vertical farms for leafy greens and other commodity crops has long been a vision of the future. Capital costs and other vagaries have prevented such development to date, but lower costs for technology and automation plus higher costs for labor, land and other resources, are making Kurzweil’s predictions come true. There are dozens of vertical farms around the world today with more being built.

Spread, a Japanese factory farmer with a large facility near Kyoto that serves the two metropolitan areas of Kyoto and Osaka, is nearing completion of a fully automated 52,000 sq ft facility where 98% of water will be recycled and seeding, watering, applying fertilizer and harvesting will all be automated. No earth; just shelves on top of shelves from floor to ceiling. They predict 30,000 heads of lettuce can be harvested and delivered daily throughout the year.

Propelling this indoor and vertical farming movement are three influential trends. The Boston Consulting Group, in 2015, produced a study entitled “Crop Farming 2030, the Reinvention of the Sector,” and cited (1) the steady global movement toward precision farming, (2) the availability of economical automation and robotics, and (3) the growing labor shortage as the drivers of the movement.

Vertical farming:

Food grown year round in buildings near urban centers provides many advantages: being close to the point of consumption reduces both distribution costs and spoilage. Outdoor farming is vulnerable to pests and disease, which in turn means intensive use of pesticides and herbicides causing problems with runoff as well as food safety. Vertical farms protect crops from weather and pests and reduce or eliminate the use of pesticides and herbicides. Hydroponic and aeroponic water methods save massive amounts of water compared to outdoor farming. Consequently, as these farms become more prevalent, they could provide a major new role for the ag industry to produce a wide range of commercial crops with major savings in space and water use. In the case of Spread, cited above, they are able to grow lettuce indoors using less than 1% of the water that California Central Valley growers use to grow the same product!

Agriculture accounts for around 70% of water used in the world today according to the OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development). As population and climate change progress, food needs will grow, and more efficient use of water in ag must happen as well. Vertical farms reduce water usage through recirculating hydroponics, evaporative cooling, control of in- and out-airflow, and other methods. Urban Crops, a Belgian factory farmer and technology provider uses this chart to show the benefits of vertical factory farms versus other methods:

Greenhouse and wholesale nurseries

Greenhouse technology is ideal to protect plants from adverse climatic conditions, insects and disease and to nurse, propagate and grow plants to usable and/or harvestable size. Greenhouses can be framed or inflated structures covered with glass or transparent or translucent material. Greenhouse yields are often 10-15% greater that outdoor yields, consistency and quality tend to be greater, and the growing season is longer.

Similar to vertical farms, greenhouses have high upfront costs and operating expenses, and crop selection must not require pollination. Whether plants are grown in the field or indoors, nurseries transplant, graft, or germinate plants to create seedlings for resale. Their processes are quite complex on two levels: (1) the technical aspects of growing plants which require management of the environment, plant nutrition, propagation, transplanting, irrigation, and pest and disease control, and (2) the business aspects of managing production, labor, customers, distribution and other activities associated with a business. Many nurseries use automation and some level of robotics. Harvest Automation and their mobile robots rearranging potted plants and Urbinati and Visser and their robotic transplanting devices are all examples of the levels of automation utilized in nursery operations.

Commercial and emerging providers:

- AeroFarms – A NJ indoor farmer that is marketing their technology to other prospective vertical farmers. AeroFarms grows a wide variety of leafy greens without sun or soil in a fully-controlled indoor environment using a system of aeroponic misting of the roots for faster harvest cycles, predictable results, food safety and less environmental impact.

- Aris – is a Dutch engineering and systems provider. Many of their projects are integrated with vision and robotics that identify, grade, sort and analyze everything from orchids to chickens, from potted plants to seedlings. Using their systems, nursery clients can then grade and robotically cut branches which can then be potted.

- ALCI Visionics & Robotics – A French integrator of vision and robotics technologies for meat and fish slicing and packaging and for nurseries and growers for potting plants and seed germination, analysis and classification for corn, rice and wheat.

- Conic Systems – a Spanish provider of greenhouse equipment including robotic and software-controlled grafting, seeding and planting systems.

- Demtec – A long established Belgium-based maker of a wide range of horticultural machinery including potting machines, seeders, planters and transplanters. Many of these processes have integrated industrial and mobile robots into their systems. Demtec robotics also play a big part in flat and shelf handling, packaging, palletization, and shipping.

- Egatec A/S – a Danish integrator of end-of-line packaging, boxing and palletizing systems for the ag and food processing industries.

- Harvest Automation – a Boston-area mobile robotics provider with nursery applications for spacing, a task that involves bending over, picking up one or two containers often weighing up to 22 pounds each, walking a few steps and then bending over again to place them in a predefined pattern. The company recently divested a warehousing variation on their mobile robot to better focus on ag industry applications.

- Helper Robotech – a Korean manufacturer of robotic grafting, smart seeding and other smart devices. They also make a wide range of nursery products to nurture seedlings to maturity.

- HETO Agrotechnics – a Dutch manufacturer of horticulture machines including robotic potting systems and pick and place systems for potted plants.

- Hortiplan – a Belgian integrator, reseller and provider of nursery equipment, supplies and mobile gully systems – which move in an automated way from the planting side to the harvesting station. Hortiplan also designs and sells lighting, irrigation and handling systems.

- Irmato Jentjens – An established Dutch builder of systems for automating food handling and packaging. Irmato also makes the Rombomatic, a robotic cutting system for nurseries that examines, assesses, cuts, powders and inserts cuttings into pots and other mediums. Jentjens is a funding partner in a variety of sensing and manipulation projects under the EU’s Clever Robots for Crops program. These include a sweet-pepper harvesting robot, an apple harvesting robot, precision and canopy-optimized spraying robots and other AI-based ag systems.

- Iron Ox – A Silicon Valley startup presently in stealth mode but hiring with a plan to provide a fully robotic, fully controlled environment for ag in a greenhouse growing leafy greens (lettuce, basil and bok choy) using natural light but mobile bots to move plants through each stage of development to harvesting, packaging and palletizing.

- ISO Group – a Netherlands-based supplier of automation solutions for nurseries. They adapt industrial robot technology for horticulture uses such as grafting, planting, vision inspection and replanting.

- Logiqs BV – a Dutch manufacturer of internal transport and logistics systems for greenhouses for growers of cut flowers, tree nurseries, flower bulbs, potted plants and vegetables. Their new modular GreenCube vertical cultivation system uses trays sensors and vertical transporters, also with sensors, for movement between layers and movement to and from the various stages of nursery growing operations.

- CMW Horticulture – a UK integrator and reseller of a whole range of greenhouse and nursery automation products including Logiqs mobility and handling systems

- Mirai Group – A Japanese farmer that, in 2009, became a member and leader of the Japanese government public-private consortium to develop low-cost plant factories. Today Mirai provides R&D and design-build services to grow leafy plants for farmers interested in vertical farming similar to what Spread is doing. Mirai is also producing and wholesaling leafy vegetables from a large plant factory located near Chiba, Japan.

- Photon Systems Instruments – An established Czech Republic provider of ag instruments including high throughput conveyor and robotic nursery phenotyping systems.

- Priva Group – a Dutch engineering, design and systems integrator for greenhouse nurseries. Recent projects include developing a leaf-removing robot for tomato plants. The lowest leaves of tomato plants are regularly removed to promote ripening (this process is called de-leafing).

- QUBIT Phenomics – a Canadian provider of conventional and robotic plant screening systems for nurseries and growers. The company’s PlantScreen™ Field Phenotyping System allows growers an automated non-invasive measurement of photosynthesis, leaf biochemical status, water status and canopy temperature. Greenhouses are the primary marketplace but the company hopes to break into field operations as well. Many major biotech companies and universities have partnered with Qubit in the study of plant responses to various stresses.

- Spread – A Japanese lettuce grower, is constructing the world’s largest plant factory near Osaka and Kyoto. The new factory, scheduled for mid-2017, will be as robotically automated as possible. Spread’s existing facility, from which they are learning what tasks can be automated, produces 21,000 heads of lettuce per day using LED lighting, controlled air conditioning and recirculating water. Spread is planning to construct and operate 20 new factories in the next 5 yearsin addition to selling the technology for others to build their own plant factories.

- Urban Crops – A Belgium startup pioneering the distribution of robotized vertical farming and plant factories. The company offers two types of products, one fits into a 40’ container and can be fully automated or not, and another is custom built for larger spaces. Currently the company has made a small number of sales and has partnered with companies such as Belgocatering, a Belguim based catering company, and a UAE group of investors.

- Urbinati – an Italian manufacturer of nursery technology including automated, and in some cases robotic, seeding, pot filling, transplanting, handling and irrigation devices. They also sell backroom processing robots such as palletizers.

- Transplant Systems – a NZ integrator and reseller of nursery machinery and robots from Urbinati and others.

- Visser – a Dutch provider of horticulture automation systems and complete production lines for large and small nurseries and greenhouses including a robot seeder, transplanter and packing and palletizing robots.

Agricultural Robotics: 160+ profiles

Working together with Tractica, a Colorado research firm, my team and I compiled a list of over 200 global businesses and agencies involved in developing robotic solutions for the ag industry. From that list, I was able to interview and profile over 160 companies and 16 research labs as follows:

- Academic and research labs (16)

- Backroom and post processing (5)

- Dairy and milking (10)

- Drones, analytics and data service providers (26)

- Farm equipment manufacturers (23)

- Harvesting, weeding and thinning robots (21)

- Hobby farming (2)

- Indoor and vertical farming (23)

- Integrator, distributor and reseller (20)

- Self-driving vehicles (15)

- UAS/UAV vendors (15)

This research report will be published in the next few weeks and will contain the whole list, the profiles, and the conclusions drawn from the research, interviews and analyses. The report will be $4,200 for a Basic License (1-5 users) or $6,300 for an Enterprise License.

Note: the link to the report is to the previous report with the same title and will be updated with new information just as soon as the new report is published.

Frank Tobe is the owner and publisher of The Robot Report, and is also a panel member for Robohub's Robotics by Invitation series...read more

agriculture roboticsrobohub focus on agricultural roboticsTractica

Glorious Green Office In Tokyo A Showpiece For Urban Agriculture

The Pasona Group’s blooming headquarters doubles as a promotional tool for farming

Glorious Green Office In Tokyo A Showpiece For Urban Agriculture

The Pasona Group’s blooming headquarters doubles as a promotional tool for farming

BY PATRICK SISSON NOV 28, 2016, 11:23AM EST

Tokyo’s streetscape typically leans towards the modern and mechanized, crowded with bright signs, busy neon lights, and new office towers. But a few blocks from the city’s main train station, the nine-story office of a progressive human resources firm presents a more pastoral addition.

The headquarters of the Pasona Group, one of the country’s largest staffing and talent agencies, literally blooms, a garden in the sky that provides Tokyo with a striking display of foliage. More than 100 types of roses grow on the building’s “green curtain” exterior during the late springtime, and in autumn months, vines growing on the trellised facade display fall colors. And that’s just the outside. The ground floor entrance, lined by citrus plants such as limes and kumquats, leads to a lobby with a functioning rice paddy and urban farm.

“We’re trying to broadcast what you can do in a metropolitan environment,” says Yukie Yoneyama, who works for the company’s urban farm division, which began seeding and planting the midcentury office building in 2010.

Pasona’s investment in a greener office isn’t just about creating a better environment for the company’s more than 1,500 Tokyo employees, though the plant-filled tower does create a less-stressful workplace and cut the building’s annual carbon emissions by 7-8 tons. The living office is part of a larger strategy by the self-described “social solutions company” to help catalyze rural economies and live up to its mission to provide jobs where they’re needed. It’s a physical manifestation of Pasona’s philosophy.

Company founder Yasuyuki Nambu started the staffing agency in 1976 to help provide jobs to mothers looking to re-enter the workplace. As the company grew over the last few decades, Nambu’s social justice focus has expanded to embrace numerous issues in Japan via an array of subsidiaries (Pasona Heartful, for instance, provides jobs for the disabled).

Over the last few decades, the combination of an aging population, a long-term recession, and unemployment has hit the Japanese farming sector hard. Nambu’s proposed solution to the crisis is to “make farming cool again,” investing in ornate projects like the urban farm, which seeks to re-connect city dwellers with agriculture, and funding community-focused businesses in rural areas.

The Pasona HQ certainly offers a sleek, camera-ready model of urban agriculture. With 43,000 square feet of space dedicated to growing more than 200 kinds of crops, nearly every corner of the Kono Designs-created office features some spin on urban agriculture. One of the conference rooms features overhead trellises holding ripe, red tomatoes, while apples and blueberries grow on the grass-covered rooftop. The indoor rice paddy, built from scrap wood and harvested multiple times a years, anchors an employee lobby, which hosts regular concerts during lunch hour. A floor of open meeting spaces includes hydroponic growing systems for herbs—small containers for sprouting seeds are hidden inside benches—offering aromatherapy between appointments. Rows of lettuce plants, raised in a “vegetable factory” along with other produce, help provide more than 10,000 meals a year in the employee cafeteria.

“One of the biggest benefits growing indoors is that we don’t need to worry about seasons,” says Yoneyama, while pointing out the special lighting and watering systems that run throughout the building. “Under normal conditions, lettuce takes 60 days from seed to harvest. We can grow it here in about 45 days.”

In a country where produce prices can by sky-high, Yoneyama says the aim of the company’s agriculture program isn’t to cut costs—rather difficult, when factoring in the cost of indoor lighting—but to spur development. Regional development has been a high priority for many companies, and Nambu believes spurring entreprenurial opportunities is the solution.

“The agricultural industry was hit by all these forces at the same time, so the question is, how do you help the agriculture and tourism industries they depend on?” she says.

In effect, Pasona’s green office is a commercial for regional development, turning normally staid downtown commercial space as a promotional tool. The rice strains planted in the lobby all come from areas hit hard by the 2011 tsunami. The company also supports a farm on Awaji Island, in south-central Hyogo Prefecture, that helps train future farmers and promote local agriculture (products such as dressings and sauces are sold in the company’s lobby).

Long-term, the company plans to continue supporting and promoting small-scale, regional farms and companies, and offer its expertise on urban farming to interested companies or architects. With a renewed focus on corporate social responsibility and healthier workspaces, Pasona fields inquiries from around the world.

“This is something that can really take off and provide a lot of benefits,” says Yoneyama. “We want to look outward.”

Green Acres Are Flourishing On Campus Rooftops Across The Country

Sustainability-minded green roof projects are appearing from Montreal’s Concordia to the University of Saskatchewan

Green Acres Are Flourishing On Campus Rooftops Across The Country

Sustainability-minded green roof projects are appearing from Montreal’s Concordia to the University of Saskatchewan

Leanne Delap

November 28, 2016

Rooftop gardens are having a moment at Canada’s universities. The eco-benefits of green roofs cycling storm water away from the sewage system, combined with the health and social benefits of growing fresh food for consumption right on campus, make the concept a win-win.

Ryerson has been ahead of the urban farming curve. About 10 years ago, says Mark Gorgolewski, a professor in the department of architectural science, CarrotCity.org was formed. “A group of architecture students were interested in food issues,” he says, “and wanted to do thesis projects that addressed the relevance of architectural design to urban food growth, preparation and enjoyment.”

From this student work flourished a website database, a book, a symposium and a travelling exhibition. By 2011, the group was involved in early efforts at growing food in various underutilized spaces around campus. In 2013, production was centralized on (and elevated to) the 10,000-sq.-foot Ryerson Urban Farm atop the George Vari Engineering and Computing Centre. The rooftop had been built as a green space, and from its opening in 2003, when it was known as the Andrew and Valerie Pringle Environmental Green Roof, it has been planted with day lilies and some 80 varieties of local weeds.

All those weeds created “rich, organic life” in the soil, says Arlene Throness, the Urban Farm manager, which they sheet-mulched and deepened for food production.

The Urban Farm now operates on a five-year crop rotation; there are 30 different crops and hundreds of cultivars. Members from the student body, staff and surrounding community all tend to the space and take home a basket of food a week as return on investment. Some produce is sold on campus at a farmers’ market; some is sold to campus kitchens. The yield, says Throness, is some 8,000 lb. a year.

The architecture connection still stands, though Urban Farm also crosses over into other faculties at the school, including nutrition, as well as environmental sciences.

The green is spreading: At OCADU there is a greenhouse that operates with no electricity and can produce lettuce in the dead of winter. Trent, the University of Toronto and Concordia all have greenhouse gardens in the sky.

And at the University of Saskatchewan, an opportunity arose on top of the phytotron (a research greenhouse). The condensers were moved, leaving a bare expanse visible from an open walkway.

“Aha,” said Grant Wood, a professor of urban agriculture, who worked with the university’s office of sustainability to come up with “the rooftop.” After getting the engineering students to check on load-bearing weights, and “a lot of paperwork,” says Wood, pallets and recycled containers were moved onto the roof. The team started with 500 sq. feet of planting, for a yield of about a thousand pounds of produce this past year; the goal is to double that next year.

The garden is being used as a teaching space for both university classes in various disciplines and agricultural camps for school kids over the summer. Crops are sold to campus food services, which advertise the fresh bounty the way restaurants point to local suppliers on their menus.

“We grow the veggies, sell them to culinary services,” says Woods. “They feed students and staff and then put the waste into a dehydrator that goes back into compost. It all takes place in less than a mile. We are working in food feet: sustainability at its ultimate.”

The Future of The Future Farmers of America

With more than 650,000 members, FFA is teaching a new generation dedicated to feeding the world’s growing population.

The Future of The Future Farmers of America

With more than 650,000 members, FFA is teaching a new generation dedicated to feeding the world’s growing population.

Nov 28, 2016

Sarah Baird is a writer and editor based in New Orleans.

As long as I can remember, I’ve coveted a jacket.

Nothing that you’d find on any runway in Milan, though, or draped over the shoulders of a peacocking Kardashian. Instead, from the time I was a preteen, the piece of outerwear that has made my Kentucky-raised heart skip a beat is the signature jacket of the Future Farmers of America.

Equal parts structured and supple, rugged and genteel, the midnight blue showpiece always seemed to encapsulate what I cherished about growing up in a farming community—though I was never particularly adept at fixing tractors or birthing calves.

For years I pined after one, even tinkering with the idea of taking enough floriculture classes to maybe, just maybe, pass off getting my name looped in perfect cursive onto a jacket of my own.

But that level of scheming just never felt right. See, FFA jackets aren’t just handed out willy-nilly: They have to be earned. An FFA jacket carries with it a level of agricultural know-how and more important, pride in the work accomplished by American farmers day in and day out. The jacket, and what it means to wear one, cannot be bought.

Or so I thought.

Last year, while wandering around an antiques store in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, I poked my head around a corner to find a couple of French tourists cooing over a style of coat that was, well, quite familiar. As the girl slid her arm into one of my beloved blue-corduroy sleeves, my eyes bulged. There was no way she’d ever been within shouting distance of a shovel.

Evidently an FFA jacket can be bought—to the tune of $500.

“Oh God, she can’t wear that!” I screamed inside my head, resisting the urge to flip over a table covered with art deco ashtrays, Incredible Hulk style. Despite my own indignant nostalgia, I was struck by a difficult question: Is farming alive and well in America?

Farmland is rapidly losing out to urban sprawl, and the debate over genetically modified crops (and the sprawl of big ag) has grown more contentious than ever. Our nation’s farmers are graying, with few protégés following in their wake. This is even before we get to the financial hurdles upstart farmers face, hurdles that mount each year, with little sign of slowing.

So what do the Future Farmers of America look like today? Who are the teenagers in Indiana or Arkansas wearing the jackets I love so dearly, and what are they worried about? What kind of future do they see for themselves?

George Strait soundtrack prepped, I hit the road to find out.

•••

Nine billion.

That’s the number you’ll encounter over and over, repeated like a mantra, when talking with FFA members. It is the molten core of what drives FFA today, the organizational touchstone that motivates and centers the masses.

It’s estimated that the earth’s population will hit 9 billion by 2050. In most conversations, this fact is followed without fail by the quasi-rhetorical question: How are we going to feed all of those humans?

The statistic is so deeply engrained in the FFA psyche that it’s almost alarming not to hear a member rattle it off during conversation. Some people utter it with race-against-the-clock anxiety. For others—mostly students—the number “9 billion” is spelled out in a word bubble above their heads, the zeros floating away like an airplane contrail. It’s a quantity almost too big to fathom.

The solution to the problem, too, seems to always appear just out of reach.

“I believe in the future of agriculture, with a faith born not of words but of deeds…in the promise of better days through better ways,” the FFA creed begins. What that future looks like now, though, is perhaps more complex than ever.

Since its founding in 1928, FFA has seen tens of millions of students flow through its ranks, and over the decades, has become a primary example of both a youth organization with influence (it does a good deal of lobbying) and phenomenal staying power.

Larry Case, who served as national FFA advisor between 1984 and 2010, believes that two turning points significantly altered the makeup and spurred the growth of the organization.

The first was when membership was opened up to women. “They opened up membership to girls in 1969, and thank goodness they did that,” he said. Today about half of all FFA members are female, including all but one member of the 2015–16 national leadership team. What’s more, at almost every FFA school I visited, women were some of the most vocal supporters of agricultural education.

The second critical juncture came in the late 1980s, when Case and his team began pushing teachers to expand and diversify the FFA curriculum—adding a focus on agri-science and biotechnology—to attract students who weren’t from traditional farming backgrounds.

“This broadened curriculum is the main thing that I believe attracts a larger base of students,” Case said.

The approach worked better than anyone could’ve imagined. Over the past 10 years, FFA numbers have ballooned to almost 650,000 members ages 12 to 21 nationwide. There are now 7,859 chapters in all 50 states, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands, and FFA students earn $4 billion annually through their hands-on work experience.

The shift led to another stat that, like “9 billion,” regularly works its way into conversation with FFA members: 210, which is the number of career pathways FFA supports. Many would-be future farmers see the old standby ag careers—rancher, commodity crop grower, family-farm inheritor—as less desirable, or realistic, choices.

“A huge misconception is that if you're in FFA, you're going to graduate and go be a farmer,” said 2015–16 National FFA Secretary Nick Baker. “While that is certainly an extraordinarily admirable profession, there’s also agricultural mechanics, agricultural technology, genetic engineering, and the veterinary field. I mean, the list of job options really goes on and on.”

FFA has also gobbled up the remnants of what used to be called vocational education; welding, carpentry, electrical work, and mechanics all fall under the FFA banner, more or less, not to mention futuristic-sounding gigs like flavor technologist and biosecurity monitor.

From an organizational perspective, this hand-over-fist growth means ensuring fund-raising efforts are kept at an equal clip.

FFA is a nonprofit and looks not only to alumni and individual givers as a means of monetary support but to corporations such as John Deere and Monsanto. (Although FFA received a federal charter in 1950, it receives no federal funding.) A cursory glance at the money trail shows that it’s pretty much impossible to divorce FFA from big ag and big pharma. For starters, Monsanto and Zoetis (the billion-dollar animal pharmaceutical company) both donate upwards—way upwards—of a million dollars a year in both general giving and individual scholarships.

And the ties go beyond financial support. In 2014, Brett Begemann, the president of Monsanto, was the keynote speaker at the National FFA Convention. When FFA decided to move and expand its national office in 1998, the land for the new building was given to them by Dow Chemical. The headquarters are smack-dab behind a shopping center built on what is assuredly former farmland.

Overall, corporate giving makes up 94 percent of FFA’s annual budget.

•••

David Tucker is what most people would believe to be the dictionary definition of an FFA student, the kind of kid for whom wearing the blue-and-gold jacket is nothing short of a birthright.

A towheaded, good-natured 16-year-old with a small stature and a lopsided smile, Tucker is a sixth-generation cattle farmer and president of the FFA chapter at Locust Trace AgriScience Center in Lexington, Kentucky. He has always known cattle farming would be his future.

“I learned to count using calves that was just born,” Tucker said, laughing and toying with his faded ball cap bearing the logo of a local stockyard. “’Two cows plus two cows equals four cows.’ That’s how I counted. It took them forever to teach me I didn’t need to say cows after the number.”

Located next to a penitentiary on the outskirts of town, Locust Trace is a five-year-old, 82-acre public vocational high school, complete with two barns, state-of-the-art greenhouses, a food science kitchen, a veterinary lab, and six-and-a-half acres devoted solely to gardening. At the school of 315 kids—most of whom split their days between here and their regular schools—it’s not hard to notice how Locust Trace weaves sustainability into all facets of its campus. The school prides itself on net-zero energy consumption, using industrial-size fans as a main source of cooling throughout its building as well as photovoltaic solar panels. It collects rainwater for irrigation and even has fashioned an underground cistern to hold the collected rainwater in case of drought.

When I arrived, principal Ann Stewart DeMott, a fifth-generation farmer, was shooing away a couple of barn cats that live in her office. (Bella and Spirit serve as “therapy felines” for kids with anxiety.) The school is full of students from all different backgrounds, she told me, most of whom have little—if any—farming experience. No matter: They get the hang of things quickly. In an era when kids are helicopter-parented ad nauseam, these ag students are retooling antique tractors by hand and mucking out stalls for school credit by the time their first semester is up.

“My dad works for Toyota, and my mom is a teacher. I hadn’t been closer than 40 feet to a horse before I came here,” said Dion Compton, 17, as we walked past the campus stables. Dion, one of several African American students at Locust Trace, has a twang that makes it seem like he’s been around farms forever. “I mean, I’d been to SeaWorld and knew I liked animals, but didn’t think that’s something I could do.” Now, when he graduates, he’ll be attending an equine technical school to make horses his career.

There’s a lot of pride to go around at Locust Trace, especially when it comes to hands-on experience. A visit to the veterinary lab found students in scrubs, learning all about how to properly measure an animal’s weight, height, and body temperature. A couple years ago, students took the bones from a recently deceased horse and reconstructed them for use as a learning tool. They nicknamed the skeletal horse Persephone. No one is squeamish.

In the equine barn, Amanda Berry—a student with a frizzy shock of dishwater blond hair—talked to me about how expensive it is to take care of farm animals, all while a horse named Taco rattled his feed bucket behind her. Will Bischoff hoisted a baby goat on his chest as he explained how a new Harry Potter–themed game he has created for the school has helped him to learn leadership skills. When we made it to the livestock barn, Tucker trotted out an orphaned calf named Sassy, showing her off like a pro.

The challenges that farmers will face in the future are never far from the minds of students at Locust Trace, especially when it comes to loss of local farmland. “The towns are growing into the farmland around here, and that’s a big issue,” Tucker said. “Also, a lot of these kids have no clue where their food comes from. They think it just magically appears at Kroger. We will have to teach them that it comes straight from the field, where we’ve had to take care of it and raise it. It’s had a life”—he paused reverently—“so it can help keep us healthy and keep us fed.”

•••

A pinprick of a destination nestled in the heart of Kentucky’s former tobacco country, Robertson County feels about as anticorporate as a place can be.

Meet the farmers working to solve the problems of tomorrow, today.

We’re fortunate here. We have a really supportive community and a supportive administration for our ag program,” said Frank Gifford, the FFA advisor. In the next room over, his first-year students were in the middle of a canning lab, chopping up and cooking down tomatoes to make salsa from scratch.

Despite its size, Robertson County is perhaps the most quietly entrepreneurial chapter I visited. Among a range of projects—from selling bobwhite quail to making vinyl signage—the FFA chapter started beekeeping two years ago and during the last harvest, bottled and sold 200 pounds of honey from 10 hives. (I happily accepted a jar of my very own.)

“We try to generate at least enough money to put it back into the projects and make them stronger. If we make a profit above and beyond, we use that money to start something else. From the greenhouse sales to livestock sales to honey sales to ag mechanics projects, our ag program is financially self-sufficient,” Gifford said.

One of the Robertson County students’ biggest concerns echoes an issue Kentucky FFA Executive Secretary Matt Chaliff has identified: How do farmers in remote areas get their products to a larger market, and more important, how do they compete—in terms of price, quantity, and more—once they get there?

“If you think about a student [farmer] in far eastern Kentucky, like Perry County, if they’re growing some kind of vegetable, they need to have that [produce] ready at just the right time,” Chaliff said. “Then, they’re two hours away from a large city market. And if you think about a fresh product, like sweet corn, making sure that they have an actual market before they grow it is a critical component.”

That’s before they’re even in front of a consumer.

•••

While rural schools like Robertson County are still FFA’s bread and butter, urban and suburban chapters seem to be gaining the most steam, and attention, on a national level.

City- and suburb-based programs comprise 27 percent of the FFA membership today, but with the momentum that’s building, it’s clear the number is only going to tick upward. There are already FFA chapters in 19 of the 20 largest U.S. cities.

At Seneca High School in Louisville, Kentucky, the agriculture curriculum all but fizzled out before Kristan Wright took over the program a little more than six years ago. Now, two classrooms are bursting at the seams with students, creatures, and colorful craft projects: skeletal models made out of dried pasta, FFA seals constructed from paper plates, illustrations of animal digestive systems.

The students at Seneca talked about agriculture like they had something to prove. Many expressed that because they live in an urban environment, they have become makeshift evangelists proclaiming the importance of farming to their city-dwelling peers.

“There’s such a huge divide between rural and urban life,” said Lexie Hughes, her hands moving emphatically. The daughter of a hairdresser and a truck driver, she is perhaps the most vocal of her peers. “Urbanizing everything in agriculture is the future. Rural agriculture is going away. It’s gone.”

Aaliyah Moss—who cites Food, Inc. (a Participant Media film) as her favorite movie and wants to be a biotechnologist—felt similarly. “Agricultural literacy is so important. Something we do really well at Seneca is take the urban aspect and the rural aspect, and we put them together for people to understand,” Moss said.

“And if I could add something?” Hughes interrupted. “It’s the youth that are redirecting the future of agriculture. I feel like we’re such an outspoken generation. We want to know everything about everything. We’re such curious people, and we’re going to educate ourselves about all the different kinds of agriculture rather than just seeing it as cows, sows, and plows.”

In Beech Grove, Indiana—a bedroom community outside of Indianapolis that feels like a Midwestern Mayberry—FFA advisor Chris Kaufman agrees.

“When we started the program here at Beech Grove five years ago, the idea was to get urban students who have no experience with agriculture more in the pipeline to get jobs at [places like] Eli Lily,” Kaufman said. Indianapolis is a hotbed for big drug companies, and their influence on the surrounding communities is difficult to miss. “One of the issues is that we’re three or four generations away from the farm, so even common farm practices, kids just have no idea. Being so far removed, you forget that you need to be a part of it.”

A former traveling agricultural education specialist for the state of Indiana, Kaufman also feels students in urban settings are often fed what he calls misinformation about organic versus conventional farming.

“Since we’re so far removed from the farm, people start hearing these buzzwords like ‘organic’ and ‘GMO-free’ and get excited about it. In reality, those are more marketing schemes than anything. If you go out in the country and ask a kid if he cares about GMOs, he’s going to say no. But in the city, if you tell a kid that something’s GMO-free, they’re going to be like, ‘I’ll pay more for it!’ We’re just tricking people into thinking these things are better for them, when they’ve not been proven to be better or more beneficial.”

And so the debate begins.

•••

How to talk to students about organic farming is a controversial topic within FFA.

“We present all the information we can and let the students make an informed decision,” said Sheila Fowler, vice principal at the Chicago High School for Agricultural Sciences. An hour later, I saw an example of this in the plant science classroom, where students were comparing and contrasting the merits of guerrilla gardening versus conventional farming versus GMOs. It felt refreshing.

But this kind of democratic approach seems to be more the exception than the rule. When I asked Nick Baker how frequently he encountered teachers offering up information about organic farming, it was clear that it was still fairly unusual.

“Organic farming isn't quite as prominent as your conventional agricultural practices, but I will say this: I have been very impressed with the open-mindedness of agriculture teachers this year to teaching about organic farming,” Baker said in a measured tone. “A lot of times in the ag community, you're conventional or you're organic, but you're not both. Really, when it comes to this industry, in my opinion, it needs to be a ‘both and’ kind of situation.”

When it comes to GMOs and the rise of large-scale, newfangled farming technologies, such as drones and no-till farming, opinions get even more complicated. “GMOs are good for you, and they’ve been made to feed the entire world,” said Ayden Paulson, a junior from Seneca who likes to score points in FFA debate events by riling the other team about PETA. “When you hear ‘genetically modified,’ you automatically think that it’s bad. But GMOs make sure our food is safe, and we’re trying to make it better for everyone.”

Not everyone in his chapter agrees. “A problem is everything is becoming more industrialized. Bringing different technologies to farms, it means less work for the people, and the less we work, the less we learn. Technology is making things easier but causing things to be worse at the same time,” chapter mate Moss said with a shudder.

“Plus, that’s where the pink slime comes from.”

“Sustainability” is a complicated term and one with a strangely malleable meaning within FFA circles. There’s environmental sustainability, sure, and there’s protecting public health and animal welfare, but most FFA members are far more concerned about the sustainability of the human population. (There’s that 9 billion stressor again.) In most cases, this means embracing any and all new technologies, chemicals, and agri-science solutions that allow for more food to be grown on smaller plots of land—whether or not it tinkers with plant DNA or pushes small farmers out of business.

If you need confirmation that large-scale agriculture is attempting to co-opt the word “sustainable,” simply visit the Monsanto website, where the conglomerate bills itself as “a sustainable agriculture company.” If nothing else, the company recognizes the importance of reshaping words for its own benefit.

Of the hundreds of scholarship competitions FFA offers at the national level (with sponsors such as Monsanto, DuPont, and CSX), only one focuses on or rewards innovative student ideas for organic production.

•••

If Locust Trace teased out the notion that ag-specific schools might be the key to the future of farming, then the Chicago High School for Agriculture Sciences strongly seconded the motion.

The last working farm in the city of Chicago, located on the South Side, CHSAS is the national gold standard for agricultural high schools—rural and urban alike—and the envy of many an FFA advisor. From Indiana to Louisiana, its reputation precedes it.

Founded in 1985, the school prides itself on being a part of the national effort to “broaden the scope of teaching in and about agriculture, beginning at the kindergarten level and extending through adulthood.” It’s an ambitious goal but one that has been embraced with vigor. Boasting more than 70 acres of cooking labs, tractor barns, and mechanic garages, the school is a role model in every possible way.

“Don’t forget to take her to the barn!” Fowler reminded my student tour guides, one of whom was wearing a sweatshirt with a photo of her dog printed on it. They assured her that everything was under control, then went back to explaining all about the new agriculture “pathway” (essentially, a career prep trajectory) in biotechnology. It will fall in line with six other categories—including horticulture and food science—that CHSAS students use as a vocational and curriculum guide throughout high school.

Along the way to the barn (which was pretty special in its own right), we passed some phenomenal scenes, the likes of which were completely foreign to my notion of a classroom. We strolled through a garage where students were power drilling high up on a platform while below, others sorted pumpkins they’d grown, then harvested from the field with a tractor. We visited the CHSAS farm stand, an after-school shop on school grounds that’s open to the community and sells products, like zucchini bread, grown and hand-crafted by the students. I heard about the fully functional tiny house students constructed two years ago for the Chicago Flower and Garden Show, and how each pathway contributed something unique to the process. (It’s still for sale, if you’re interested.)

CHSAS farm stand on campus in Chicago sells various seasonal vegetables picked by the students. (Photo: Scott Thompson)

Even though you can see strip malls off in the distance, CHSAS feels like its own world. There are cornfields, cabbage plots, and a freshly planted apple orchard. Somewhere beyond a baseball field, cattle graze. The students laugh as they tell me about how the cows sometimes escape, roaming into the middle of a busy road and the lot of a nearby Ford dealership.

“I can’t imagine someone driving down the middle of 115th Street, then being like, ‘What is this cow doing here?’ ” Nicole Stallard, one of my tour guides, said, doubling over with the giggles.

•••

“Family” is a popular word in FFA circles.

Ask anyone—and I mean anyone—in an FFA chapter if he or she feels kinship with fellow members, and the student will likely explode with praise for his or her ag-loving brothers and sisters. Heck, even without asking, I came to expect that chapter members would tell me within seconds of meeting just how much affection there is to go around. There’s a sort of tenderness about FFA students that comes perhaps from working closer with the earth—tending to sick animals, nurturing fledgling plants. Unlike the majority of their teenage peers, they seem to have a larger purpose, understanding, and respect for their place in the world.

What’s more, the FFA chapters I visited were not only more racially and socioeconomically diverse than I expected but also incredibly welcoming of students with learning or developmental disabilities. Inclusion, it seems, is a point of pride among many FFA chapters.

Nathan French from Seneca says the impact FFA has had on his life is extraordinary.

“Everyone in FFA is like family to me. Freshman year I was mostly sick, so I didn’t do anything, but sophomore year I finally found a talent for impromptu speeches, thanks to two fantastic teachers,” French said, grinning. Not only did he win first place at the Kentucky FFA regional competition last year for speaking about beef, but he took home the top prize in the talent competition for a dance he choreographed to a Black Eyed Peas song.

As one might imagine, building a familial culture starts with supportive teachers, and FFA advisors are nothing if not beloved. The recent swell in agriculture programs across the country means that ag teachers are also in high demand, especially in places that traditionally haven’t been hotbeds of FFA action.

“I’ve been at the school...forever?” JaMonica Marion, FFA advisor at CHSAS, said, laughing. A 2001 graduate, she officially returned to teach in 2006. “The majority of the teachers in our ag department are now alumni, so we get to provide the students with firsthand knowledge. We can actually relate to them because we were in their seats.”

At times, the intimacy found at the chapter level feels in stark juxtaposition to the highly formal national structure of the organization, embodied most readily by the national FFA officers. A group of six peer-elected students, the officers serve as the face and fearless leaders of the organization, even taking a year off from schooling to devote themselves to 365 days of FFA-related lobbying, fund-raising, and general hype.

Grooming for national FFA office begins early, with state FFA officers whisked away each year on a (corporate-sponsored) international trip to learn about agricultural production in such countries as Japan and South Africa. They’re also sent to several forms of leadership boot camp, the biggest of all being the one for national officers at Tyson Farms.

Tyson CEO Donny Smith is a proud FFA alum and a huge role model for Nick Baker, who hopes to be an agricultural lobbyist after serving in the Marines.

“[Smith] usually spends about two or three hours every year with the national officer team talking about leadership. He compares [leadership] to a peach tree,” Baker said. “We [as national officers] are the roots; we are supplying the FFA members with what they need in order to be successful. Then they can go be the peaches that people see and admire about this tree that is our organization.” He paused.

“It's always interesting to get to visit with Mr. Smith.”

Whatever leadership training they’re doing, it’s working. The interpersonal and public speaking skills the national officers possess are impressive, and their fervor can border on proselytizing at times. For the most part, they stay on message better than most elected officials I’ve met and are both personable and persuasive in their arguments. It’s not difficult to see why hundreds of thousands of young people have faith in them.

Today, FFA has grown to such staggering heights nationally that it seems to more closely resemble a political party than any sort of school club. The sheer number of members alone is a little baffling, and the power that could be wielded by 650,000 young people rallying around a single cause is a sensational, or terrifying, thing to think about. It has revolutionary potential.

If anyone knows this, it’s the students (and, uh, maybe some corporations).

•••

For all the momentum behind the youth agriculture movement, one thing still strikes me as kind of odd: Since 1988, FFA isn’t even the Future Farmers of America anymore—at least, not technically. Just like Kentucky Fried Chicken is now just an acronym, KFC, FFA’s official name is simply the National FFA Organization.

We’re so much more than farming and ranching these days. It’s a good thing! National advisors and officers will argue. To some degree, that’s true. But I can’t help feeling a twinge of sadness that farming has been lost, in name, from its very own organization.

So what will the exalted FFA heroes of tomorrow look like, if not traditional farmers?

In 2014, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History ran a campaign in search of five exemplary FFA members “whose lives and careers have been shaped by agricultural education.” The honor was, undoubtedly, pretty grand. After ascending to national glory, the personal FFA jackets of these handpicked ag titans were to become part of an exhibit at the museum celebrating agricultural innovation and heritage.

President Jimmy Carter's FFA Jacket, which is displayed in the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History in Washington DC. (Photo: Courtesy the Smithsonian)

After a months-long search, the selected winners were announced, and they clearly represented the diversity of FFA’s membership. Among others, there was Corey Flournoy, the first African American national president, and Karlene Lindow Krueger, a pioneering Wisconsin hog farmer. Former President Jimmy Carter was the cherry on top, “Plains, Georgia” emblazoned on the back of his blue-and-gold jacket.

So when they do an all call 50 years from now for the next round of distinguished alumni, will the chosen few be organic rabbit breeders or scientists who grow meat in labs? Compost revolutionaries or mechanics who work on no-till farming? Ag-drone scientists? Or all of the above?

While the paths of our future agricultural leaders remains to be seen, it’s safe to say that today, FFA students hold a respect for the land and an optimism about building a better world that is unmatched. The kids I spoke to are not only hopeful but purposeful and ready to take up their larger mission on the planet to do what they believe is best.

“Knowing that the first job on this earth was a farmer and the last job will be a farmer,” Taylor McNeel, 2015–16 national FFA president, explained, taking a long, deep pause. “It’s pretty cool to be a part of that.”

Container Farms Add Local Flavor To Fresh Fruit Production

French startup Agricool believes the fruit flown around the world and stacked onto supermarkets shelves ain't what it used to be, so it has hatched a plan to recapture the authentic flavors of yesterday's fresh produce

Container Farms Add Local Flavor To Fresh Fruit Production

November 24th, 2016

Agricool focuses on growing fruit in its shipping container farms, rather than leafy greens(Credit: Tony Trichanh)

French startup Agricool believes the fruit flown around the world and stacked onto supermarkets shelves ain't what it used to be, so it has hatched a plan to recapture the authentic flavors of yesterday's fresh produce. The company has just raised €4 million (US$4.2 million) in funding to develop specialized shipping containers that can be used to grow full-flavored fruit a little closer to home.

The firm's fresh fruit approach sets it apart from similar shipping container farm outfits like Cropbox and Freight Farms, which typically focus on leafy greens. The first fruit that Agricool is focusing on is the strawberry, a produce it says is the poster-boy for tasteless supermarket fruit.

Agricool kits out its shipping containers as hydroponic growing units, designed to optimize growing conditions like nutrient levels, irrigation, LED lighting and CO2. The air drawn in from outside is filtered in an effort to minimize the possibility of pollution entering the containers.

"We have 30 engineers in house, working all day to improve the technology," company co-founder Guillaume Fourdinier explains to New Atlas. "If you don't do that, you are only able to grow leafy greens. Our mission is to bring back taste in our fruits and vegetables, and we don't feel that it has been lost for leafy greens."

Vertical grow-walls, rather than stacked trays, are used as this is said to make it possible to grow more per square meter, with each container able to house more than 4,000 strawberry plants. Agricool says each container can produce 120 times more than would be the case on the same area of a field. The crops produced are also claimed to be more vitamin-rich, free of harmful chemicals and pesticides and conveniently, don't need washing before they're eaten.

The closed loop system employed for water and nutrients uses 90 percent less water than would be required for conventional cultivation and only electricity from renewable sources is used. What's more, the basic tending of the containers can be done by people with no experience in farming, while Agricool actually monitors the health of the crop and controls water and nutrient feeds remotely.

Only 30 sq m (323 sq ft), or the area of two car parking spaces, is required for each container. It is hoped that this distributed mode of growing can ultimately serve whole urban areas, while also helping to cut transportation time, costs and emissions.

Agricool was founded last year by Fourdinier and his colleague Gonzague Gru, both children of farming parents, because they couldn't find high-quality fruit and vegetables in cities. This, they say, is because crops are harvested too soon so that they don't spoil during transport and because they're chosen for their ability to travel, rather than for taste.

The firm's first prototype was installed in Bercy, in the 12th arrondissement of Paris, France, late last year and there are now three prototypes in operation. It has spent this year conducting research and development, and the new funding will be used to speed up Agricool's growth, with the goal for next year to roll-out 75 containers, distribute 91 tons of strawberries and begin work on two new types of crop.

Source: Agricool

Veggie Plant Growth System Activated on International Space Station

May 16, 2014

Veggie Plant Growth System Activated on International Space Station

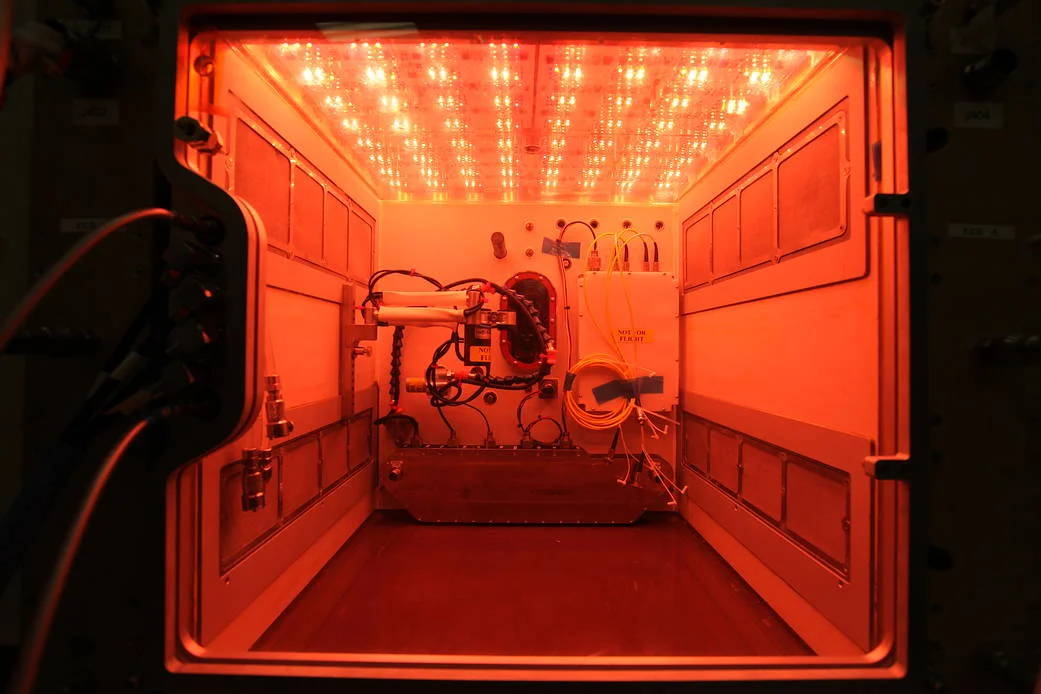

Expedition 39 flight engineer and NASA astronaut Steve Swanson opens the plant wicks in the Veggie plant growth system May 11 on the International Space Station. The six plant pillows contain 'Outredgeous' red romaine lettuce seeds.

Researchers activated the Veggie plant growth system May 9 inside a control chamber at the Space Station Processing Facility at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida to shadow the activation and procedures being performed on Veggie on the International Space Station.

By Linda Herridge

NASA's John F. Kennedy Space Center

If you plant it, will it grow—in microgravity on the International Space Station? Expedition 39 crew members soon will find out using a plant growth system called “Veggie” that was developed by Orbital Technologies Corp. (ORBITEC) in Madison, Wisconsin, and tested at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

The first fresh food production system, along with the Veg-01 experiment, were delivered to the space station on the SpaceX-3 mission from Cape Canaveral in April and transferred to the Columbus module for storage until it was time for in-orbit activation.

Expedition 39 flight engineers and NASA astronauts Steve Swanson and Rick Mastracchio installed Veggie in the Columbus module May 7 in an Expedite the Processing of Experiments to the Space Station (EXPRESS) rack.

Wearing sunglasses, Swanson activated the red, blue and green LED lights inside Veggie on May 8. A root mat and six plant "pillows," each containing 'Outredgeous' red romaine lettuce seeds, were inserted into the chamber. The pillows received about 100 milliliters of water each to initiate plant growth. The clear, pleated bellows surrounding Veggie were expanded and attached to the top of the unit.

Inside each plant pillow is a growth media that includes controlled release fertilizer and a type of calcined clay used on baseball fields. This clay increases aeration and helps the growth of plants.

Dr. Gioia Massa is the NASA science team lead for Veggie. She sees Veggie and Veg-01 representing the initial steps toward the development of bioregenerative food production systems for the space station and long-duration exploration missions.

"The farther and longer humans go away from Earth, the greater the need to be able to grow plants for food, atmosphere recycling and psychological benefits," Massa said. "I think that plant systems will become important components of any long-duration exploration scenario."

About 24 hours after Veggie was activated on the space station, back on Earth, "pseudo-naut" researchers activated identical plant pillows in the Veggie control chamber in the International Space Station Environmental Simulator laboratory at Kennedy's Space Station Processing Facility. Researchers will monitor the plant growth and perform the same procedures as Swanson is doing on the space station.

"My hopes are that Veggie will eventually enable the crew to regularly grow and consume fresh vegetables," Massa said.

One of the plant experiment's goals is to verify the Veggie hardware is working correctly. Another goal is to establish that the space lettuce is safe to eat.

On the space station, the Veg-01 plants will grow for 28 days. Photographs will be taken weekly, and water will be added periodically. The pillow wicks were opened to help the seedlings emerge. As the plants grow, the pillows will be thinned to one plant per pillow, and microbial samples will be taken to check for any microorganisms that may be growing on the plants. At the end of the cycle, the plants will be carefully harvested, frozen and stored for return on the SpaceX-4 mission later this year.

Veggie will remain on the station permanently and could become a research platform for other top-growing plant experiments. ORBITEC developed Veggie through a Small Business Innovative Research Program. NASA and ORBITEC engineers and collaborators at Kennedy worked to get the unit's hardware flight-certified for use on the space station.

"Veggie could be used as a modular plant chamber for a variety of plants that grow up rather than in the ground," said Gerard Newsham, the Veggie payload support specialist with Jacobs Technology on the Test and Operations Support Contract. "This is just the beginning."

Another set of six plant pillows, containing 'Profusion' Zinnia seeds could be activated in Veggie for the Expedition crew to grow and enjoy as they wait for word that the red romaine lettuce is safe to eat. If the lettuce is safe to eat, Massa said an additional set of plant pillows containing the romaine lettuce seeds will be activated in Veggie.

"I hope that the astronauts on the space station eventually will use the equipment to 'experiment' with their own seeds or projects," said Nicole Dufour, who coordinated and led the testing of the flight hardware at Kennedy and wrote the crew procedures for the astronauts to use on space station. "Veggie is designed for crew interaction and to enjoy the plants as they are growing."

Dufour said she hopes Veggie serves as a regular facility the crew uses to grow food crops. Dufour is an engineer in the Flight Mechanisms and Flight Crew Systems Branch of the Engineering and Technology Directorate.

Brian Onate, former Veggie project manager, helped shepherd the plant growth system from initiating the build of the flight units in 2012 to just a couple of months before its delivery to the space station.

"I hope to see Veggie's success as the first step in food production that will allow astronauts on the space station to enjoy fresh food and gain knowledge as we explore beyond low-Earth orbit," Onate said.

Why Vertical Farming Is More Than Just Growing Indoors

Feeding urban populations is especially challenging in a linear system. We need to grow food as close as we can to the people who need it

Why Vertical Farming Is More Than Just Growing Indoors

Nicolette Maio · November 22, 2016

As part of Circulate’s collaboration with the Disruptive Innovation Festival, we’re featuring insight from some of this year’s Open Mic contributors in advance of their performance at the DIF. Find out more at thinkdif.co, and don’t forget to catch up on this session with a panel of vertical farming experts.

Feeding urban populations is especially challenging in a linear system. We need to grow food as close as we can to the people who need it. Instead of transporting foods from every corner of the earth, we need to grow food directly in the cities and create more local economies based on necessity. Where we do that can vary: from a vacant lot, a rooftop, in a greenhouse, or even inside of a building.

Farming indoors has its fans and its critics, but it becomes a practicality as the populations of cities increases. Many people are thinking into the future for what food production hubs should look like for sustainable cities of the future.

Could we be on the verge of creating hybrid forms of food production? Can the indoor farmer and the bio-nutrient farmer find common ground? Will Allen is a key figure in knowing how to farm for the future. His revolutionary ways as an urban grower demonstrate the brilliance of a closed-loop system. His organisation, Growing Power, based out of Milwaukee, WI, has implemented greenhouses with stacked functions. The bottom level is an aquaponics system, which feeds the fish poop to the plants’ roots, then circulates back to the fish tank as clean water. It is not just about growing indoors, it is about creating a closed loop that reuses and eliminates waste.

Let’s think bigger. It’s also about incorporating alternative energy instead of fossil fuels wherever possible into the indoor growing system. In Suwan, South Korea there is a three-story 450 metre squared building that the Rural Development Agency is utilising for vertical farming. They have sourced nearly 50% of their heating, cooling and artificial lighting requirements to renewable resources, such as geothermal and solar power. More experimental models like this one are urgently needed.

Permaculture enthusiasts would say, “the problem is the solution.” Where does the potential for growing indoors lie? Could empty warehouses and abandoned buildings be repurposed as mushroom farms? Can sustainable energy be a bigger part of the closed loop? As crazy as it may sound, can harvesting insects provide a new source of protein and reduce the demand for factory-farmed meat? How we grow, what we grow, and where we grow will be shaped by the innovators of today.

Visit thinkdif.co to find out more about the Disruptive Innovation Festival. Don’t forget to create My DIF account to build your own schedule, get session recommendations based on your interests, and 30 days of bonus catch up time after the DIF has ended.

Agricool Harvests $4.3 Million To Grow Fruits And Vegetables In Containers

DISRUPT LONDONDisrupt London Starts Today - It's Not Too Late To Get Tickets Get Yours Today

Agricool Harvests $4.3 Million To Grow Fruits And Vegetables In Containers

Posted Nov 22, 2016 by Romain Dillet (@romaindillet)

French startup Agricool has raised $4.3 million (€4 million) from newly launched VC firm Daphni as well as Parrot founder Henri Seydoux and Captain Train (acquired by Trainline) co-founder Jean-Daniel Guyot. Agricool’s product is quite unusual as the company wants to grow strawberries and later other fruits and vegetables inside shipping containers.

With many people moving to mega-cities, it has become increasingly difficult to provide good food to people living in these cities. In just a few decades, there will be many, many cities with tens of millions of people living there. It’s a logistical and environmental challenge.

That’s probably one of the reasons why processed foods have taken off. It’s so much easier to ship across great distances instead of relying on perishable goods.

And yet, many cooks are trying to reverse this trend, looking for fresh and local ingredients for their recipes. It’s a good trend, but it also means that you’re limiting your options, especially in places with a hostile weather.

Why do we keep seeing the same bright red tomatoes that never go bad and don’t taste like anything? Intensive farming has been great to fight hunger issues, but it’s time to look further — in this case, it means going back to what makes food tastes great in the first place.

Agricool is trying to do something about this and started with strawberries. Instead of relying on trucks filled with strawberries coming from Turkey, Germany, Spain or Italy, the startup tried to produce strawberries right where they were, in Paris.

If you can control the light, the water, the substrate and other factors, the startup noticed that you can grow strawberries anywhere — including in a shipping container.

Then, it’s a matter of optimizing all these factors so you can produce more strawberries from a single container, or cooltainer as the company calls them. The company doesn’t want to use any pesticide and my guess is that it’s going to take a while to make these strawberries as cheap as existing strawberries.

The company is now renting a big warehouse to fill with containers. There’s probably a fair share of A/B testing going on, but with fruits and not website designs. With today’s funding round, Agricool wants to create 75 containers in 2017 and install them around Paris — the goal is to produce 91 tons of strawberries.

The startup also wants to test other crops soon. Maybe some vegetables and fruits will be harder than others when it comes to growing them in a container. It’s going to be a long, capital-intensive venture to iterate on those containers. But it’s an interesting take on the food industry.

Vertical Farming: The Future of Agriculture?

For those of you unaware of the quiet revolution going on in agriculture, vertical farming is shaping the future of food

Can This Modern Cultivation Practice Of Growing Plants In A Closed Environment Meet Our Food Demands In A More Sustainable Way?

For those of you unaware of the quiet revolution going on in agriculture, vertical farming is shaping the future of food.

World population is expected to reach a colossal 11 billion by 2100 (though it varies depending on whose model you use). As a result, many have begun to askhow are we going to feed even more hungry mouths? The answer, at least in part, comes in the form of vertical farming, a new, revolutionary, and sustainable way to grow our food that can also help to reduce the carbon footprint of food production.

Vertical farming involves growing plants in stacks of hydroponic towers, lit with LED lamps, in a strictly controlled environment. The towers of crops are fed with water laced with nutrients, the strict control of the environment allows for optimum yield from the crops every time. Global Vertical Farming market was worth 600 million USD in 2014.

Vertical farming has numerous advantages over the practices of regular farming. As well as producing a consistent and high yield crop 365 days a year, the crop can be grown in a compact and protected environment — one that is not affected by weather patterns or climate change. All with the added bonus of zero waste (through water recycling) and zero net energy use. All the water used in the hydroponic stacks is recycled and reused — urban waste water can even be recycled for use in vertical farms.

Green Sense Farms in Portage, Indiana, is in the process of building a network of indoor vertical farms across the globe. Their goal is to not only reduce the carbon footprint and environmental consequences associated with traditional farming, but to provideconsumers with locally produced, fresh, leafy greens, to try to foster healthier and more environmentally friend communities. Green Sense Farms is using LEDs built by Dutch tech giants Philips to cut power costs through cheaper LED light, as well as tweaking light wavelengths to try to grow the perfect crop. The Economist praised their farms for the innovative work that they are doing to provide new ways to better feed the planet:

“The crops grow faster, too. Philips reckons that using LED lights in this sort of controlled, indoor environment could cut growing cycles by up to half compared with traditional farming. That could help meet demand for what was once impossible: fresh, locally grown produce, all year round.”

The versatility of location is the greatest strength of vertical farming, especially in the fight against climate change. The farms can be located at, or nearby to, distribution centres, supermarkets, or anywhere that sells or serves large volumes of food, and thus reduce the carbon footprint associated with transporting food from farms to tables – it is the antithesis of globalization.