Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

Ag Company Grown in Portage Has Global Aspirations

The founder of a Portage-based commercial farming operation believes his indoor farming methods can be a sustainable solution throughout the world

Ag Company Grown in Portage Has Global Aspiration

By Dan McGowan, Writer/Reporter

PORTAGE -

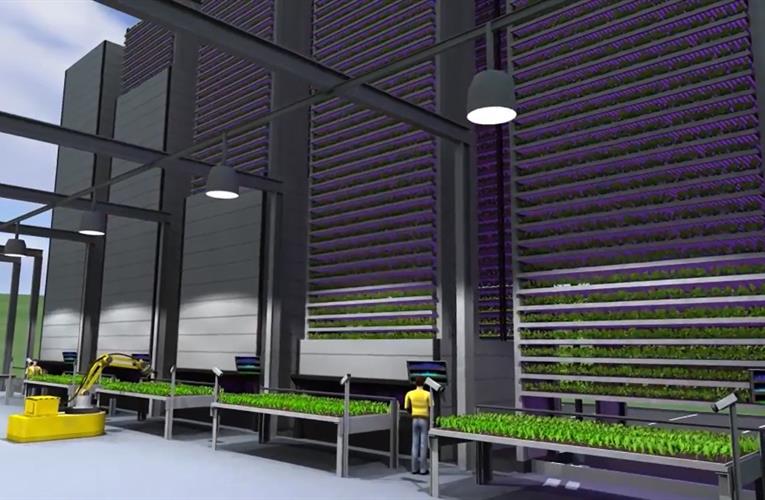

The founder of a Portage-based commercial farming operation believes his indoor farming methods can be a sustainable solution throughout the world. Chief Executive Officer Robert Colangelo says Green Sense Farms LLC's vertical farming model allows consumers to buy produce right where its grown, which can be in a building "virtually anywhere." The company's goal is to first build networks throughout the U.S., Canada, Scandinavia and China and then continue to spread globally. Plants, which are grown on racks that reach as high as 24 feet, are kept in constant growing conditions through lighting, watering and feeding processes Green Sense Farms says uses only a fraction of the resources of traditional farming techniques.

In an interview with Inside INdiana Business, Colangelo said "we are the modern, new farmer."

Colangelo is a third-generation Chicagoan but says he's happy to be a transplant in the Indiana agribusiness community, which has been very supportive of what he's trying to accomplish. He adds that northwest Indiana is an "iconic" location to have a business. "We're at the bottom of Lake Michigan on the Crossroads of America, Interstate-94 and 65, they tell me that we can reach 80 percent of the U.S. population in a day's drive from where we're located."

Colangelo tells Inside INdiana Business all future farms will be located "where large volumes of meals are sold," which includes grocery chain hubs, military bases, corporate campuses, schools or hospitals. "We put our farm here (in Porter County) originally, because we were close to the Midwest distribution center for Whole Foods in Munster," he said. "What we've learned is that close isn't good enough. You really want to be inside the distribution center." The Portage farm, Colangelo says, is the largest commercial, indoor vertical farm in the country.

The company's first farm in China opened in August and through a partnership with Ivy Tech Community College, Colangelo says ground will be broken soon on a new farm in South Bend, which will supply area universities, hospitals and grocery stores. He says 10 other spots are currently in the development pipeline.

Green Sense Farms says some characteristics of the markets it continues to scout include:

- large population centers

- high numbers of educated consumers who pay a premium for produce that is GMO-, pesticide- and herbicide-free

- produce travels a great distance

- growing seasons are short

- resources like land, clean water and clean air are limited

Colangelo says recently-loosened crowd-funding regulations have opened up his company to more potential investors. Indeed, Green Sense Farms has launched an online fundraising campaign, which has led to commitments totaling more than $200,000 in two weeks. You can connect to more about the crowdfunding efforts by clicking here.

Urban Produce To Hire Indoor Growers

Prospective growers will attend Urban Produce University in Irvine to prepare to work for prospective licensees in China, Canada, Mexico and Japan in 2017, according to a news release

By Mike Hornick October 03, 2016 | 1:44 pm EDT

Urban Produce, Irvine, Calif., plans to hire Controlled Environmental Agriculture indoor organic vertical growers to support its licensees as part of phase two of the company’s expansion program.

Prospective growers will attend Urban Produce University in Irvine to prepare to work for prospective licensees in China, Canada, Mexico and Japan in 2017, according to a news release.

Urban Produce, which launched in January 2015, holds patents in seven countries including the U.S. and Canada.

“As we move into the next phase of our business we look forward to building vertical growing units all over the world,” Ed Horton, President and CEO, said in the release.

With world population projected to increase 70% by 2050, Urban Produce’s plans for expansion aim to help combat global hunger and eradicate food deserts.

“Our goal of sustainability incorporates our atmospheric water generation and the use of solar-generated power in order to build anywhere,”

Certhon And Korean Lettuce Producer Sign Agreement

The Korean lettuce producer and Certhon, leading expert in designing and implementing complete greenhouse projects, signed an agreement to develop and realize a high-tech automated hydroponic greenhouse facility

Certhon and Korean lettuce producer sign agreement

30 September 2016

In the presence of Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte and Minister for Agriculture Martijn van Dam, a Korean lettuce producer and Certhon signed an agreement .This agreement was signed September 27th at the Netherlands-Korea Trade Dinner in Seoul during an economic mission in South Korea to confirm the collaboration between the companies.

The Korean lettuce producer and Certhon, leading expert in designing and implementing complete greenhouse projects, signed an agreement to develop and realize a high-tech automated hydroponic greenhouse facility of 1,4 ha. Moreover, there is a desire for the construction of a demonstration greenhouse of approx. 3000 m2 for hydroponic lettuce production, located in Gyeonggi-do (South Korea). Certhon will take the lead in the outline, design and realization of the project.

The companies signed the agreement during an economic mission in South Korea, led by prime minister Mark Rutte, accompanied by sixty Dutch companies of the top sectors Agri Food, Horticulture and Creative Industries to further strengthening the already close bonds between the Netherlands and South Korea.

Kimbal Musk and Dan Barber Clash About The Future of Food

September 28, 2016 — 8:36 AM CDT

Kimbal Musk, co-founder of farm-to-table restaurant group the Kitchen, board member at Chipotle, Tesla, and SpaceX, and younger brother to Elon, thinks hydroponic vertical farming—that is, soil-less, indoor, LED-lit agriculture—is the future of food.

Dan Barber, renowned chef, restaurant owner, author of bestseller The Third Plate, and crop rotation evangelist, strongly disagrees.

In August, Musk announced a new venture called Square Roots. He hopes it will get millennial city dwellers to become farmers—who grow their goods in shipping containers. In his Medium post, he described “campuses of climate-controlled, indoor, hydroponic vertical farms, right in the hearts of our big cities.”

Chef Dan Barber (left), Kimbal Musk (center), and Elly Truesdell speak onstage at The Next Kale and Quinoa panel at the New York Times Food For Tomorrow Conference 2016 on Sept. 27, in Pocantico, N.Y. Photographer: Neilson Barnard/Getty Images for The New York Times

Musk's vision calls for containers with hydroponic vertical farming technologies, controlled temperatures, artificial lighting, and soil-less nutrition. At the New York Times Food Conference on Tuesday at Barber’s Blue Hill at Stone Barns in Pocantico, N.Y., Musk explained how lights inside the containers can be dialed to yield particular flavors and, most of all, how it can bring young people into farming industry. The influx of young blood is badly needed. The average age of farmers climbed from 50.5 years old in 1982 to 58.3 years old in 2012.

Musk is hardly the first to champion vertical farming. Frequent travelers may have noticed the aeroponic model at Chicago’s O’Hare airport, where such herbs as purple basil and chives grow alongside vegetables, including green beans, Swiss chard, and Bibb lettuce, year-round. Companies like Vertical Harvest in Jackson Hole, Wyo., FarmedHere in Bedford Park, Ill., and Alegria Fresh in Irvine, Calif., are also betting on versions of the new technology. A 2015 report by New Bean Capital, Local Roots, and Proteus Environmental Technologies hailed indoor agriculture as "the next major enhancement to the American food supply chain."

Proponents boast about the water saved, the pesticides avoided, and the faster growing times in an environment in which seasons don’t matter.

Not everyone, though, is on board with dirt-less farming.

“It’s not making me hungry,” Chef Dan Barber told the audience at a panel on new food trends. Barber is a preacher of the power of soil. He often explains how crop rotations—growing not just wheat, but also legumes, rye, and lesser known plants—not only provide tables with more diverse foods but improve the flavor of the primary crops, such as the wheat itself.

“I’d rather invest intellectual capital into the soil that exists outside,” said Barber, though he added that he doesn't know much about vertical farming. Still, he wants to see more excitement about what goes on underground, instead of growing food above it. “When Kimbal says you can dial in the flavor and colors you want, I don’t know that I want that kind of power,” Barber said. “I’d rather have a region or environment express color and flavor.”

Elly Truesdell, the Northeast regional forager—a fancy term for buyer—for Whole Foods Market, agreed with him. “I’ve never had a piece of produce from a hydroponic grower that tastes as delicious to me [as the soil grown version],” she said on the panel.

Both Musk and Barber agree that the current corn- and soy-centric agricultural system that grows more feed for animals than food for humans is broken; they just see vastly different solutions to the problem.

Even Musk isn’t pretending that shipping containers are already producing the big league results he's promising. “We buy 99.99 percent of our products from soil-grown foods,” he admitted of his restaurants.

Why ShopRite and Compass Group Have A Taste For Urban Farming

Vertifical farms startup Aerofarms can control pests and tweak produce flavors by changing the spectrum on the LED lights it uses within urban warehouses

Why ShopRite and Compass Group have a taste for urban farming

Wednesday, September 28, 2016 - 2:18a

Vertifical farms startup Aerofarms can control pests and tweak produce flavors by changing the spectrum on the LED lights it uses within urban warehouses.

Will the U.S. urban agricultural movement become mainstream? It’s certainly about to garner far more visibility, thanks to legislation proposed this week by Sen. Debbie Stabenow (D-Mich.), a ranking member on the Senate’s committee for Agriculture, Nutrition and Forestry.

Her bill, dubbed the Urban Agriculture Act of 2016, would expand the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s support for farm cooperatives in metropolitan areas, make it simpler for farmers running rooftop gardens or vertical farms to apply for USDA programs and fund research into new water and energy technologies that might accelerate adoption. Stabenow introduced her ideas in Detroit, a fertile example of what’s possible with the right public and private sector focus.

"A steady increase in the number of urban farms in the Capital City is beginning to impact health and nutrition awareness, good food access and food security, even as it is transforming fragile neighborhoods," noted Joan Nelson, executive director of the Allen Neighborhood Center, which runs a wholesale market for local produce and foods in Lansing, Michigan.

Although it’s a long way from becoming law, debate on the Urban Farm Act could help bring new legitimacy to the farmers, gardeners and technologists cultivating this movement. While no one really believes urban farms will be capable of supporting all of the food needs of their home cities, they’ll definitely be part of the solution, according to experts speaking last week at VERGE 16 in Santa Clara, California.

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations estimated last year that about 15 percent of the world’s food supply was attributable to farms or greenhouses in urban locations.

There’s a romanticized notion of local food production, and there’s a complete underappreciation of the complexity involved to be successful.

"I really see the future of agriculture in the ag of the middle sector," said Helene York, global director, responsible business for giant foodservice company Compass Group, during a keynote interview at VERGE. "Not in really big ag, not in really small ag. Not in hyper-local and not in global. But really about where do we find the best locations to grow some of the best food."

York is affiliated with one of Compass’ highest profile accounts, Google. While she’s not at liberty to discuss the sources that the technology company is studying for its corporate cafeterias and catering operations, she’s researching ingredients such as sustainably farmed seaweed. Kelp fettuccine, anyone? It could become a menu item, if we’re willing to set aside preconceived notions of taste.

"I am optimistic in the role of technology working with private industry as well as governments," York said.

Advancing food 'literacy'

One of the more important roles that urban farming operations will play is in advancing food literacy, and teaching urban citizens to appreciate organic produce that isn’t readily available in some lower-income neighborhoods. In San Francisco, for example, thousands of schoolchildren visit Alemany Farm, a site of several acres bounded by freeways, near public housing, and created from a former junkyard. There they can taste food that isn’t necessarily bred for shipping, so that that have a better appreciation for the concept of fresh.

The power of urban agriculture, in this case, is really education.

"The power of urban agriculture, in this case, is really education," said Eli Zigas, food and agriculture director for the nonprofit organization SPUR, during a VERGE panel. "They come and volunteer, they get their hands in the dirt and they learn about food and where it comes from. I think that’s one of the most valuable things, if not the most valuable thing, that urban agriculture provides to a city, and why a city would want to have it.”

Urban farmers that try to compete head-to-head against rural, organic farming operations will find it difficult to compete profitably. Rather, municipal governments should consider policies that frame and support urban farming operations in the context of a broader regional network.

"We’re going to have a national and international food system for a very long time," Zigas said.

Growing economic opportunity

For vertical farms specialist Aerofarms, urban farming is as much about creating new jobs as it is about reshaping the food supply, according to company’s co-founder and CEO David Rosenberg.

This week, the company opened its ninth aeroponic facility, housed in a former, converted steel factory in Newark, New Jersey. Aerofarms uses special lights to grow plants on trays stacked vertically to maximize growing space. (The new Newark facility has 13,000 of them.) These lights can do everything from deterring insects (sans pesticides) to tweaking the flavor of a leafy green. Rosenberg said his company can produce up to 22 crop turns per year.

"Our productivity per square foot is about 75 times higher than for a field farmer," he told VERGE attendees, adding that the approach uses about 95 percent less water.

Aerofarms is forging relationships with nearby grocery chains, such as New Jersey-based Wakefern Food, which owns the ShopRite supermarket co-op chain. Its crops are delivered to local distribution centers, where they can be shipped to where demand is greatest. The produce commands about the same price as organic field farmers.

Aerofarms also sells to the corporate foodservice company Compass Group, with which it is working on new recipes that are pushing people to think outside of traditional eating habits. One example: The two organizations are addressing the food waste dilemma by experimenting with ways to use all of a vegetable, including the stems.

"There’s a romanticized notion of local food production, and there’s a complete underappreciation of the complexity involved to be successful," Rosenberg said.

Local Food Is Great, But Can The Concept Be Taken Too Far?

The commonly held belief that reducing “food miles” is always good for the environment turns out to be a red herring.

The commonly held belief that reducing “food miles” is always good for the environment turns out to be a red herring.

One of the most interesting developments in American agriculture during the last decade has been the rise of the local food movement.

It’s incredibly popular. People love the idea of eating food that is grown nearby on surrounding farms. It helps increase the sense of authenticity and integrity in our food. Also, the food can often be fresher and tastier. Many folks also like that the supply chain — the path food travels from the farmer’s field to the dinner fork — is shorter, is more transparent and supports the local economy. And who doesn’t love going to a wildly colorful farmer’s market or a beautiful farm-to-table restaurant and learning more about the farms and farmers who grew our food? No wonder local food is so popular.

Local food can also be good for the environment, especially if it reduces food waste along the supply chain. Many local farms are organic or well-run conventional farms, which can produce many benefits to soils, waterways and wildlife. And, in some places, local grass-fed ranches are trying to sequester carbon in the soil, offsetting at least part of beef’s hefty greenhouse gas emissions. Done right, local food can have many environmental benefits.

Without a doubt, local food has a great set of benefits. But the commonly held belief that reducing “food miles” is always good for the environment because it reduces the use of transportation fuel and associated carbon dioxide emissions turns out to be a red herring. Strange as it might seem, local food uses about the same amount of energy per pound to transport as long-distance food. Why? Short answer: volume and method of transport. Big box chains can ship food more efficiently — even if it travels longer distances — because of the gigantic volumes they work in. Plus, ships, trains and even large trucks driving on interstate highways use less fuel, per pound per mile, than small trucks driving around town.

But don’t feel bad. It turns out that “food miles” aren’t a very big source of CO2 emissions anyway, whether they’re local or not. In fact, they pale in comparison to emissions from deforestation, methane from cattle and rice fields, and nitrous oxide from overfertilized fields. And local food systems — especially organic farms that use fewer fertilizers and grass-fed beef that sequesters carbon in the soil — can reduce these more critical emissions. At the end of the day, local food systems are generally better for the environment, including greenhouse gas emissions. Just don’t worry about emissions from food miles too much.

Without a doubt, local food has a great set of benefits. And it’s just getting started.

From Local to Super-Local

We have also seen a movement toward what you might call“super-local” food, where people grow more food right in the city. In other words: urban agriculture.

There are commercial scale urban farms popping up, like Growing Power in Milwaukee, that grow food in vacant lots and create badly needed jobs in urban neighborhoods. Others, like Gotham Greens, are growing food in rooftop greenhouses in major cities. People are also starting community gardens in their neighborhoods, where folks can share an area of land — maybe in a city park or a school yard — to grow fruits and vegetables. And, of course, many people grow super-local food at home, in their yards, or on their patios and decks. In fact, my wife and I have always grown salad greens, herbs, vegetables, and a wide range of fruits at our place — whether in a tiny yard converted to gardens and orchards in Saint Paul, Minnesota, or a variety of potted vegetables, herbs, and fruit trees on a deck in San Francisco. It tastes great, and there is a lot of satisfaction in doing it yourself. And I love that our daughters grew up — even as city kids — knowing a little bit about where food comes from.

While it’s not a silver bullet solution to all of our global food problems, [local food is] an exciting, powerful development, and it can have important nutritional, social, economic and environmental benefits if done well.But, despite these great advances, we need to remember that urban food can’t feed everyone. There’s just not enough land. In fact, the world’s agriculture takes up about 35 to 40 percent of all of the Earth’s land, a staggering sum, especially compared to cities and suburbs, which occupy less than 1 percent of Earth’s land. Put another way: For every acre of cities and suburbs in the world, there are about 60 acres of farms. Even the most ambitious urban farming efforts can’t replace the rest of the world’s agriculture. Fortunately, urban farmers are smart and have focused their efforts on crops that benefit the most from being super-local, including nutritious fruits and vegetables that are best served fresh. In that way, urban food can still play a powerful role in the larger food system.

So there’s a lot to be excited about with local food. While it’s not a silver bullet solution to all of our global food problems, it’s an exciting, powerful development, and it can have important nutritional, social, economic and environmental benefits if done well.

Taking It Too Far: Hyper-Local Food and Indoor “Farms”

Local food is a very welcome development. But can we take it too far?

Yes, I’m afraid we can — especially when we start to grow foodindoors with energy-intensive, artificial life-support systems.

We’re now seeing what you could call “hyper-local” food, where crops are grown inside a building, whether a warehouse, an office building, a grocery store or even a restaurant. In the last few years, a number of tech companies have designed indoor, industrial “farms” that utilize artificial lights, heaters, water pumps, and computer controls to grow stuff inside. These systems glow with a fantastic magenta light — from LEDs that are specially tuned to provide optimal light for photosynthesis — with stacked trays of plants, one on top of the other.

Some of the more notable efforts to build indoor “farms” include Freight Farms in Boston. And a group at MIT is trying to create new high-tech platforms for growing food inside, including “food computers.” These folks are very smart and have done a lot to perfect the technology.

At first blush, these “farms” sound great. Why not completelyeliminate food miles, and grow food right next to, or even inside, restaurants, cafeterias or supermarkets? And why not grow crops inside closed systems, where water can be recycled, and pests can (in theory) be managed without chemicals?

But there are costs. Huge costs.

First, these systems are really expensive to build. The shipping container systems developed by Freight Farms, for example, cost between $82,000 and $85,000 per container — an astonishing sum for a box that just grows greens and herbs. Just one container costs as much as 10 entire acres of prime American farmland — which is a far better investment, both in terms of food production and future economic value. Just remember: Farmland has the benefit of generally appreciating in value over time, whereas a big metal box is likely to only decrease in value.

Second, food produced this way is very expensive. For example, the Wall Street Journal reports that mini-lettuces grown by Green Line Growers costs more than twice as much as organic lettuce available in most stores. And this is typical for other indoor growers around the country: It’s very, very expensive, even compared to organic food. Instead of making food moreavailable, especially to poorer families on limited budgets, these indoor crops are only available to the affluent. It might be fine for gourmet lettuce, or fancy greens for expensive restaurants, but regular folks may find it out of reach.

Finally, indoor farms use a lot of energy and materials to operate. The container farms from Freight Farms, for example, use about 80 kilowatt-hours of electricity a day to power the lights and pumps. That’s two to three times as much electricity as a typical (and still very inefficient) American home. And on the average American electrical grid, this translates to emitting45,000 pounds (20,000 kilograms) of CO2 per container per year from electricity alone, not counting any additional heating costs. This is vastly more than the emissions it would take to ship the food from someplace else.

And none of it is necessary.

But, Wait, Can’t Indoor Farms Use Renewable Energy?

Proponents of indoor techno-farms often say they can offset the enormous sums of electricity they use by powering them with renewable energy — especially solar panels — to make the whole thing carbon neutral.

But just stop and think about this for a second.

Any system that seeks to replace the sun to grow food is probably a bad idea.These indoor “farms” would use solar panels to harvest naturally occurring sunlight and convert it into electricity so that they can power artificial sunlight. In other words, they’re trying to use the sun to replace the sun.

But we don’t need to replace the sun. Of all of the things we should worry about in agriculture, the availability of free sunlight is not one of them. Any system that seeks to replace the sun to grow food is probably a bad idea.

Also, These Indoor “Farms” Can’t Grow Much

A further problem with indoor farms is that a lot of crops could never develop properly in these artificial conditions. While LED lights provide the light needed for photosynthesis, they don’t provide the proper mix of light and heat to trigger plant development stages — like those that tell plants when to put on fruit or seed. Moreover, a lot of crops need a bit of wind to develop tall, strong stalks for carrying heavy loads before harvest. As a result, indoor farms are severely limited and have a hard time growing things besides simple greens.

Indoor farms might be able to provide some garnish and salads to the world, but forget about them as a means of growing much other food.

A Better Way?

I’m not the only critic of indoor, high-tech, energy-intensive agriculture. Other authors are starting to point out the problems with these systems, too (read very good critiques here, here, here and here).

While I appreciate the enthusiasm and innovation put into developing indoor farms, I think these efforts are, at the end of the day, somewhat counterproductive.

Instead, I think we should use the same investment of dollars, incredible technology and amazing brains to solve other agricultural problems — like developing new methods for drip irrigation, better grazing systems that lock up soil carbon and ways of recycling on-farm nutrients. We also need innovation and capital to help other parts of the food system, especially in tackling food waste and getting people to shift their diets toward more sustainable directions.

With apologies to Michael Pollan, and his excellent Food Rules, here are some guidelines for thinking about local food:

- Grow food. Mostly near you.

- But work with the seasons and renewable resources nature provides you.

- Ship the rest.

An interconnected network of good farms — farms that provide nutritious food with social and environmental benefits to their communities — is the kind of innovation we really need. And the local food movement is making much of this possible.

Jonathan Foley is the director of the California Academy of Sciences. Follow him on Twitter @GlobalEcoGuy.

Freight Farm Lettuce Used in Campus Dining Halls on Friday

On Friday, Sept. 30, the first harvest of over 1,000 head of lettuce from the on-campus Freight Farm will be used in dining halls across campus

Thursday, October 13, 2016

Freight Farm Lettuce Used in Campus Dining Halls on Friday

Sep. 28, 2016

On Friday, Sept. 30, the first harvest of over 1,000 head of lettuce from the on-campus Freight Farm will be used in dining halls across campus.

The lettuce will be distributed to Fulbright, Pomfret, and Brough dining halls, as well as the Arkansas Union, and will show up everywhere from salad bars to burgers.

The lettuce has been growing since Aug. 11, in an insulated, "farm in a box" container.

The 40' x 8' x 9.5' container, produced by Freight Farms, is a fully functioning hydroponic farm built inside of an up-cycled shipping container.

Inside the container, LED light strips provide crops with spectrums of red and blue – the light spectrums required for photosynthesis. A hydroponic system delivers a nutrient rich water solution directly to roots, using only 10 gallons of water a day. Energy-efficient equipment automatically regulates temperature and humidity through a series of sensors and controls.

After the first harvest, the farm should consistently produce crops of up to 500 heads of lettuce.

Before bringing the Freight Farm to campus, Chartwells Dining Services, part of the Division of Student Affairs, was looking to find a sustainable solution. The project has the potential to shorten the food supply chain, cut transportation emissions, decrease transportation costs, and overall all, significantly reduce the campus carbon footprint.

Ashley Meek, Chartwells' licensed, registered dietitian and farm manager, said the freight farming project is one way of addressing campus sustainability while giving students a way to pursue their academic interest outside of the classroom. Meek has two student interns who help her manage the farm – Taylor Pruitt and Merissa Jennings – who are both interested in the future of agriculture and food sciences.

"We hope the Freight Farm supplies sustainable culinary operations to campus, and also gives those students working with the Freight Farm a place to get their hands dirty in the science behind hydroponic farming," Meek said.

Any overages from the crops are slated for donation to the Razorback Food Recovery, enabling the campus to use every bit of each harvest.

1 University of Arkansas

Fayetteville, AR 72701

479-575-2000

The US Start-Up Helping Indoor Farming Become A Growth Industry

What makes indoor farming attractive is its resource-efficiency compared with conventional farming methods.

Not so long ago, in the basement of a building in Copenhagen’s trendy meatpacking district, you could find a hydroponic garden growing leafy greens - such as romaine lettuce, pea shoots, and parsley. Oh, and dill, lots of dill. (This is Denmark, after all.)

The project was called the Farm, and it was the brainchild of Space 10, a “future-living lab and exhibition space”. Its remit is to explore possible solutions to major global challenges in order to “create opportunities for a better and more sustainable way of living”. That includes the future of food – and indoor farming in particular.

Hence the Farm – which, in its own way, typifies a shift in thinking about farming methods. According to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the global population will hit nine billion by 2050. And to feed all those people, food production must increase by 60 to 70 percent by 2050. Little wonder, then, that seemingly radical ideas like indoor farming are being considered as possible solutions.

What makes indoor farming attractive is its resource-efficiency compared with conventional farming methods. In fact, according to Agrilyst, which creates “intelligent indoor farming platforms”, hydroponics requires about 10 times less land and 20 times less water than conventional farming.

The trouble is, indoor farming still gobbles up a lot of energy and resources – which is what makes Agrilyst’s indoor farm-management platform interesting. The US start-up claims it enables farmers to monitor and optimise plant performance, and use fewer resources and less energy in order to produce a greater yield. Another way of putting it is that Agrilyst’s platform helps farmers become more sustainable and profitable.

The platform tracks and analyses indoor farm data in one place – enabling farmers to monitor and maintain optimal plant performance, and therefore reduce operating expenses. In particular, farmers receive real-time analytics and data aggregated from hardware, such as crop sensors, as well as lab results and spreadsheets.

At the same time, Agrilyst uses the data aggregated on the platform, coupled with academic research and industry knowledge, to develop new solutions for optimising performance. Its aim is therefore to make indoor farming easier, greener, and more productive.

From an environmental perspective, the platform’s appeal is apparent: it uses data analytics and recommendations to help indoor farmers to reduce energy and resource use. The economic case is clear, too: by aggregating data from indoor farms around the world, Agrilyst provides growers with insight and intelligence to improve performance – in turn helping to increase yield and profits.

Critically, the social aspect stems directly from this: by increasing yield and quality, indoor farmers can provide their communities with better tasting, healthier, and safer produce, while contributing to the global need for increased food production.

Platforms such as Agrilyst’s seem to make it easier than ever for farmers to say hello to hydroponics. Indeed, if you’ll excuse the pun, indoor farming is fast becoming a growth industry. Experiments in indoor farming may be taking place in the basement of buildings in Copenhagen. But they won’t be underground for much longer.

This innovation is part of Sustainia100; a study of 100 leading sustainability solutions from around the world. The study is conducted annually by Scandinavian think-tank Sustainia that works to secure deployment of sustainable solutions in communities around the world. This year’s Sustainia100 study is freely available at www.sustainia.me – Discover more solutions at @sustainia and #100solutions

This Singapore Device Turns Your Home Into An Urban Farm

Creator Brian Ong hopes his device will help people grow and eat more fresh, wholesome food

This Singapore device turns your home into an urban farm

Creator Brian Ong hopes his device will help people grow and eat more fresh, wholesome food

26 Sep, 2016

The late founder of modern Singapore, Lee Kuan Yew, rolled out a plan in 1967 to transform the republic into a “garden city”; today, parks and gardens green spaces adorn the city’s urban landscape amidst the ever-growing high-rise developments.

Even in HDB flats, many Singaporeans are fond of keeping potted plants along the dreary-looking corridors.

But the problem with urban life is that time constraints create unhealthy gardening habits. So unless it’s cactus or a similarly resilient plant, many plants die from the neglect and lack of water.

Brian Ong, a Masters of Architecture graduate from the Singapore University of Technology (SUTD), has created a device that helps urban farmers/botanists automate plant care.

There is no team behind Hydra. Ong as a one-man inventor, and was spurred to embark on this project because of his own pain point.

“This project started off when I was in university. As my schedule got busier, my plants began to suffer as a result. As I could not find any suitable watering solutions for the indoor garden (the systems I came across on the market had various shortcomings), I decided to design one for myself,” says Ong, in an interview with e27.

Another factor was the growing trend of urban farming, In a nutshell, the concept revolves around urban dwellers growing high-quality produce within confined spaces, in a sustainable fashion.

“More people are striving to grow their own mini edible gardens to provide a small but steady stream of herbs and vegetables to their kitchen,” he says.

Ong took to taking apart and scrutinised the shortcomings of current indoor watering systems on the market.

“Some systems are difficult to install in existing indoor setups – for example, drip systems that require a connection to a tap,” he says.

“Other systems are not very discreet – for example, capillary action solutions (water channelling) that have one bottle per pot or gravity solutions that require the water source to be placed above the pots. Some systems also run on battery power, which is not good for everyday use,” adds Ong.

The solution

Thus, the findings came to one clear-cut conclusion – Hydra needs to be a simple plug and play device.

Hydra essentially acts as a hub and “is designed to be simple to install in any existing indoor/balcony garden setup and easy to maintain. It draws water from a bucket on the ground and distributes it to up to 10 plants via tubes once a day,” says Ong.

“Each output’s watering volume can also be adjusted independently of one another, so the needs of different plants can be catered to,” he adds.

For those who seek to build a mini indoor farm, Ong says it is also possible to water more than 10 plants if the pots are set up in a way that allows water to be drained from one pot to the next. Water can also be pumped up to a 2.25 metres height.

The user also can plug in multiple sources of water, so it’s possible to water plants for weeks without refilling the water source(s). And once the system has been properly rigged up, the user can start calibrating the sequence.

First, the current time and water dispensing time have to be set. Then comes dispensing volumes, which can be set in three different ways: visual dispensing (see a rough gauge of much will be dispensed), preset volumes, and volumetric dispensing (meaning specific user set volumes).

It’s not smart

One surprising thing about Hydra is that — despite the trend of IoT devices such as this — it is not smart.

Ong opted for the low-tech route because “a smart watering system would have incorporated soil moisture sensors in each pot, which would have increased costs and led to a whole bunch of wires running around the place.”

The goal, Ong emphasises, is to create a simple automated watering machine without bells and whistles.

Development

Hydra has been in development for close to 11 months. The initial funding for the prototype and samples for various parts amounted to around S$2,000 (US$1,470).

Ong is seeking to raise capital via Kickstarter. Currently, it has raised nearly half of its S$55,000 (US$40,400).

So if you would like to go on a long holiday without fretting about your plants withering away, Hydra might be a good fit for the home.

Just remember to cover the water source(s) or your home will be ground zero for a Zika mosquito breeding spot.

Proposed Legislation Would Support Urban Farming With USDA Resources

Proposed legislation would support urban farming with USDA resources

September 26, 2016 11:00 a.m. Updated 9/26/2016

U.S. Sen. Debbie Stabenow announced Monday that she is introducing legislation that addresses the needs of urban farmers by offering them U.S. Department of Agriculture resources and programs.

Stabenow, D-Mich., made the announcement with Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan and Michigan urban agriculture leaders at D-Town Farm, Detroit's largest urban farm, on the city's far west side.

The Urban Agriculture Act of 2016 would create new economic opportunities for urban farmers through agriculture cooperatives, rooftop and vertical farms, access to research that explores marketing opportunities for urban agriculture, and developing methods for lowering energy and water needs.

The legislation is to be formally introduced this week.

“The next step (if the legislation passes) is urban farmers will have the capacity to use all of the USDA services that rural farmers have,” Stabenow said.

The bill includes $10 million to support cutting-edge farming research and it would open a new USDA office in Washington, D.C., to help urban farmers get started or improve their existing business, the senator said. Another $5 million would go toward supporting community gardens and education for nutrition, sustainable growing practices, soil remediation and composting.

It would also benefit urban farmers in large and small cities.

Stabenow said the bill builds on the farm legislation she authored and was signed into law in 2014.

“I’m going to brag a bit,” she said. “Malik (Yakini of the Detroit Black Community Food Security Network that runs D-Town) and other people involved for a long time in Detroit farming are the experts on urban farming. When I talk to folks around the country about urban farming, they say, ‘Why are you asking me? The urban farming expertise is in Detroit.’”

Yakini said at the news event that he is hesitant to comment on the legislation. “I’ve not seen the bill,” he said. “We hope it will be helpful.”

He added that legislation that would make access to capital easier for urban farms would be appreciated. “The challenges are access to capital and access to land, even though a third of the city is vacant land,” he said.

BrightFarms’ Indoor Farming System Lands $30M to Grow

Leafy greens and tomatoes don’t have to travel hundreds of miles to reach salad plates anymore.

Consumers can easily make garden salads year round because grocery stores get their greens from farms across the country where items like lettuce are always in season. But those leafy greens and tomatoes don’t necessarily have to travel hundreds of miles to reach salad plates.

Agtech startup BrightFarms uses indoor farming to try to shorten grocery store supply chains, and also lower costs by using less land, water, transportation fuel, and pesticides than traditional farming. The New York-based company announced last week that it raised $30.1 million from investors to take this greenhouse model to new markets across the country.

The BrightFarms investment eclipses the $18 million raised by Harrisonburg, VA-based Shenandoah Growers earlier this year. That company, which sells herbs and herb plants grown in its greenhouses, raised funds from S2G Ventures and Middleland Capital, according to AgFunder. Despite those deals, indoor agriculture remains a small part of overall agtech investment.

The technologies claiming most of the $1.8 billion in global agtech investments in the first half of the year were food e-commerce, biomaterials and biochemicals, soil and crop technology, and precision agriculture, according to AgFunder. That six-month total marked a 20 percent decline compared to the same period in 2015. Indoor agriculture accounted for $21 million across 10 deals in the first half of 2016—just 1 percent of all agtech funding raised and just 3 percent of all deal flow, according to AgFunder. Still, a number of startups, including BrightFarms, are betting on consumer and investor interest in indoor farming.

The indoor farming market is shaking out into several segments. BrightFarms is a food supplier, distributing the food it grows to contracted retailers, who in turn sell the produce to consumers. That’s the same approach taken by Brooklyn, NY-based startup Edenworks, which grows produce inside a warehouse and supplies stores in New York. Other companies are providing businesses with the hardware to do their own indoor farming. Atlanta-based PodPonics, for example, sells shipping containers and software to manage food-growing operations inside them. Boston-based Freight Farms also sells refashioned shipping containers outfitted with LED lights and climate controls.

Some startups are bringing indoor growing options directly to consumers. Somerville, MA-based Grove sells high-tech growing cabinets that consumers can place in their homes. And Cambridge, MA-based SproutsIO, which like Grove shares MIT roots, has developed a microfarming system that fits on a kitchen countertop.

All of these startups pledge to provide locally grown food that reduces water use and eliminates pesticides. For its part, BrightFarms claims its greenhouses use 80 percent less water, 90 percent less land, and 95 percent less shipping fuel compared with crops grown outdoors and shipped to market via conventional supply chains.

BrightFarms currently operates greenhouses near Chicago, Philadelphia, and Washington, DC. It says it has long-term, fixed price contracts to provide produce to several supermarket companies including Mariano’s, a Chicago-area grocery retailer owned by Kroger (NYSE: KR); ShopRite, whose footprint includes New York and New Jersey; and Giant Foods, which has stores in the central Atlantic states.

When BrightFarms opened its newest greenhouse in Illinois, CEO Paul Lightfoot told the Chicago Tribune that the 160,000 square-foot facility cost about $10 million, which included land acquisition and construction. In the funding announcement, the company did not say where it will use the fresh capital to expand.

Frank Vinluan is a contributing editor at Xconomy, based in Research Triangle Park. You can reach him at fvinluan@xconomy.com Follow @frankvinluan

High Times: Vertical Farming Is On the Rise — But Can It Save the Planet?

Farming as we know it is failing.

Farming as we know it is failing. Mom-and-pop operations are struggling to survive and Big Ag cares far more about its bottom line than about your health, or the health of the planet. Ecologists, anti-GMO activists, even sticker-shocked soccer moms in the produce aisle agree: It’s time for a revolution. Now, some experts are saying, this revolution may come via vertical farming, in which produce is grown indoors, in stacked layers. After years of technological trial and error, the practice is primed for blastoff.

The basic idea is not new. For centuries, indigenous people in South America pioneered layered farming techniques, and the term “vertical farming” was coined by geologist Gilbert Ellis Bailey in 1915. But the need for its large-scale implementation has never been greater. Under our current system, U.S. retail food prices are rising faster than inflation rates, and the number of “food insecure” people in the country — those without reliable access to affordable, nutritious options — is greater than it was before the era of agricultural industrialization began in the 1960s. And we’re only looking at more mouths to feed; according to the UN, the world’s population will skyrocket to 9.7 billion by 2050, an increase of more than 2.5 billion people.

Additionally, climate change is threatening the sustainability of our current food production system. Rising temperatures will reduce crop yields, while creating ideal conditions for weeds, pests and fungi to thrive. More frequent floods and droughts are expected, and decreases in the water supply will result in estimated losses of $1,700 an acre in California alone. Because the agricultural industry is responsible for one-third of climate-changing carbon emissions, at least until Tesla reimagines the tractor, we’re trapped in a vicious cycle.

So how do we break out?

“We have to extinct outdoor farming,” Dickson Despommier, PhD, emeritus professor of microbiology and public health at Columbia University and author of “The Vertical Farm: Feeding the World in the 21st Century,” told Salon. “We have to put the earth back to the way it was when trees were the most abundant crop. If we paid farmers to plant carbon-sucking trees instead of corn — what’s called carbon farming — the earth’s atmospheric makeup could be completely different in 20 years’ time. But this means looking elsewhere for a food source.”

In vertical farming, that food source starts with a building – any building – usually comprising more than one floor. On every level are flat racks of plants taking root not in soil, which is unnecessary for growth, but instead in a solid, sustainable, and pesticide-free substrate, like mashed-up coconut husk. In these hydroponic systems, plants are fed a nutrient solution from one of a variety of devices, including a misting nozzle, a slow-feed drip, and a wicking tool (like the volcanic glass called perlite) that carries nutrients from an in-house reservoir directly to the roots.

CA Farmers Use Advanced Drone Tech to Save Water http://videos.tout.com/dry/mp4/7ef39d7e62d9b298.mp4

The buildings are equipped with artificial lighting in place of sun, and they’re temperature and humidity controlled. Unlike in the great outdoors — where wind, precipitation, and season are out of a farmer’s hands — growing conditions are controlled and plants are able to reach maturity twice as fast. Often, the spaces are hermetically sealed to prevent common plant diseases, like wheat rust, from blowing through. And the final product? It tastes the same as crops grown outside, even better if those outside crops came from degraded soil. While leafy greens have traditionally been the most cost-effective crop to grow indoors, improved technology is also allowing for a broader range of options (think tomatoes, berries and ramps).

Vertical farming operations are sprouting in the U.S. and around the globe. Earlier this year, the $39 million AeroFarms, comprising 12 layers spread over 3.5 acres, opened in an old steel mill in Newark, New Jersey. Production yields the equivalent of 13,000 acres of farmland in the region. It also utilizes 95 percent less water than traditional vegetable farms since the H2O is recirculated.

In Philadelphia, Metropolis Farms, which already operates the world’s first vegan-certified vertical farm in North America, is planning a network of 10 vertical projects throughout the city, including the world’s first solar-powered vertical farm. Because the technology has advanced so much in recent months, according to president Jack Griffin, this network will cost 5 percent of what AeroFarms did, require 80 percent less real estate, and allow for a greater yield. Similar projects are seeing success in Japan and Berlin —and in Sweden, a plantagon, or plantscraper, 16 stories tall is in the works.

The goal, in addition to creating green-collar jobs, is to bring nutritious produce to urban areas where high-quality, fresh food is hard to come by. With 70 percent of the world’s population expected to reside in cities by 2050, utilizing agritecture to eliminate these food deserts is an increasingly attractive option. In the U.S., $32 million in venture capital was invested in indoor agriculture in 2014, and proponents say the industry has a revenue potential of $9 billion.

But not everyone is convinced the idea won’t go to seed. Early this year, in an article for Alternet, environmental writer Stan Cox argued against growing food in high-rises because of the method’s large energy requirement — specifically, the need for LED lighting in lieu of sunshine. Louis Albright, PhD, emeritus professor of biological and environmental engineering at Cornell University, called vertical farming “pie in the sky” for the same reason.

“The sun is equivalent to $400,000 worth of electricity per acre when growing outdoors,” Albright told Salon. “What vertical farming can save in transportation costs is quite small comparatively. It’s not viable.”

But proponents of vertical farming say such rebukes are based on outdated information — the efficiency of LED lighting has increased dramatically, by 50 percent between 2012 and 2014. Progress is expected to continue — the U.S. Department of Energy has recently adopted new LED efficiency standards, set to be finalized by January 2017. Meanwhile, vertical farms are hiring engineers and ergonomists to reduce the footprint even further.

“We designed our own LED lights to dial into wavelength spectrums,” Allison Towle, director of community engagement at the Los Angeles vertical farm Local Roots, told Salon. “We control them to emit only red or only blue or only white light, whichever helps a specific plant grow, which reduces energy output. Our R&D phase was two years long, because we developed these specific recipes, meaning for each plant we determined the right kind of lighting, the right nutrient makeup in the water, and the right amounts of each. This has brought outdoor growth times down by 40 percent.”

Robert Colangelo of the Indiana-based Green Sense Farms, which has 10 new projects in the deal pipeline, says improvements in LED efficiency are largely responsible for his current expansion, which involves building a network of vertical farms throughout the U.S., Canada, Scandinavia and China. The plan is to launch at points of consumption — grocery stores, hospitals, colleges and military bases — for direct-to-consumer sales. The food will be fresh, and the distribution-related carbon emissions, nonexistent.

“Comparing the energy requirement of growing outdoors versus growing inside is like comparing apples and oranges,” Colangelo told Salon. “We use LED lighting and they use sunlight. But they need tractors and other mechanical equipment, more water, fertilizer. It’s two different growing processes. Instead of comparing them, look at the crops and evaluate the most sustainable way to grow each one. Commodity crops, like soybeans, will likely always be grown outdoors. Leafy greens are better inside. What vertical farming has done is stratified the industry.”

In the future, some vertical farmers, like Colangelo, are looking to incorporate biopharmaceuticals into their growing rosters. And NASA, which counts itself as a vertical farming pioneer, may end up using the method for growing food on other planets, in a more sophisticated version of the techniques used in “The Martian.” But for now, the industry is still in its infancy.

“It’s like the beginning of the Internet, or even the Internet 10 years ago,” Despommier told Salon. “Look how far that’s come. There are people who looked at the airplane and thought: ‘That will never fly.’ But people are going to continue innovating. In 10 years’ time, we’ll all be getting our food this way.”

Indoor Farming Opportunity

If you’re in Dallas and interested in operating two Growtainer™ farms, please contact me by email

Indoor Farming Opportunity

If you’re in Dallas and interested in operating two Growtainer™ farms, please contact me by email. Very interesting opportunity for a couple of people that want to run their own business growing gourmet greens and supplying local restaurants. Includes all LED lighting, Climate Control, Ebb and flood system and fully equipped NFT system. Completely plug and play, just bring seeds and substrate and you’re in business. These are the original Growtainer™ prototypes at Agrilife Research Center in Dallas, available for a couple of entrepreneurs that want to run their own business. Plus you get to hang out with me….gb@greentech-agro.com

Glenn Behrman, President of GreenTech Agro announced today that the Growtainer™ version 2.0 is officially just weeks away from launch. Offered at a very competitive price with a dramatically increased potential yield, Growtainer™ 2.0 has been completely re-designed to be more affordable for a quick ROI and more efficient in every way. It’s easier to operate and comes with a maximum yield, moveable and adjustable Growrack™ system. The proprietary Growrack™ system was designed by GTA and manufactured in Holland. Growtainers™ are available in a 40’ or 45’ version and can be custom designed for any climate. Developed for food production, horticulture or floraculture, they are available with complete climate control or refrigeration for vertical vernalization.

An operator can now produce 2 to 3 times as much produce in the patent pending Growtainer™ compared to other container based products in the market today. For example: Growing in 50’s = 12,000 plants per cycle, 72’s = 17,280 plants per cycle, 98’s = 23,520 plants per cycle. You do the math, very easy to calculate the ROI.

Glenn announced that GTA is finally ready to talk to investors and to choose two or three distributors. He said at Indoor Ag that he wouldn’t sell a Growtainer™ unless it was perfect and version 2.0 is perfect.

For more information, email: gb@greentech-agro.com

www.growtainers.com

Edible Learning Lab – A Year In Growth

“Our mission is to bring edible education to all kids K through 12, and it’s something we think about all the time”

Edible Learning Lab – A Year In Growt

Nick Spanos, nick@buffalobulletin.com

On most afternoons, a magenta glow can be seen reflecting out from the eastside stairwell of the Bomber Mountain Civic Center. If you follow the light down the stairs and through the side door, you’ll find yourself in what was once the middle school’s music room, but in place of scattered music stands and an upright piano collecting dust, you’ll find a room budding with life, literally.

The converted space houses a fully functional edible learning lab complete with raised planting beds, a fully equipped teaching kitchen and a vertical hydroponic system with red and blue LED grow lights to stimulate plant growth – the source of the magenta glow.

The Edible Learning Lab program is the brainchild of admitted foodies and entrepreneurs Tim Miner and Dave Creech.

They launched the program in Buffalo last September, and in the lab’s first year of operation it has prospered, producing well over 100 pounds of food and educating hundreds of Johnson County students in the process.

“Our mission is to bring edible education to all kids K through 12, and it’s something we think about all the time,” Miner said.

Edible education means giving students hands on experience growing their own food, but it also means teaching them the biological processes that bring food from a seed to a family’s table.

Educating the kids and introducing students to healthy eating practices is something that Miner sees as invaluable.

“We think it’s important because this is one of the solutions or one of the processes that can lead to health changes,” he said.

Miner also mentioned the staggering number of health problems caused by dietary related issues in the U.S.

“We feel that educating kids at an early age is going to set them on the right trajectory. It’s going to give them understanding and love for the relationship they have with food,” Miner said. “It’s going to create a more sound foundation for that relationship, and over time kids are going to be making healthier choices and they’ll be exposed to things they wouldn’t otherwise be exposed to, and we feel that’s our way to plant the seed for change going forward.”

The strong vision that Miner has for the learning lab wasn’t always set in stone. He’ll be the first to tell you it’s been an evolving journey from day one to now.

“I would love to tell you that we had this crystal clear idea of what an edible learning lab would be, what it would look like and how it would be organized, but the reality is this has been kind of a snaking back and forth approach. When we first started working on the rough outline of the curriculum we had intended it to be for adults,” Miner said. “I was on the board of the BDTA at the time, and I was serving with Lisa (Mueller) who was the CEO of the Boys & Girls Club, and we were talking about the curriculum and I was telling her how surprised I was by the number of kids who couldn’t pick broccoli out of a line up of vegetables, and she said, ‘You’re working on the course, do you think you could apply that to kids?’”

Miner responded with an immediate yes, and when Mueller came back a week later and said she might be able to secure grant money for the project, Miner was fully on board.

Miner and Mueller worked together to prepare the grant application just before the deadline and were approved for the maximum award of $125,000 a year for five years, and after Miner and Creech reworked the curriculum and ordered the equipment for the lab, everything began to fall into place.

A year later, Miner is just putting the finishing touches on the project.

“We’re placing our last orders for equipment, we’ve fully equipped the kitchen and are working on the rain harvesting system, which will allow us to capture over 200 gallons of rainwater from the downspouts to be used in the lab,” Miner said.

The concept of the edible learning lab has always been something that Miner and Creech wanted to be applicable and repeatable on a national scale.

“The plan has always been to open as many of these labs around the ounty as possible. Right now we’re talking to about 100 schools. We’re really interested in having this information being presented to all schools around the country,” Miner said.

Vertical Farming Market worth 3.88 Billion USD by 2020, at a CAGR of 30.7%

Lighting functional device expected to lead the vertical farming market

Arshad Singh

Vertical Farming Corporate Communicator at MarketsandMarkets

Vertical Farming Market worth 3.88 Billion USD by 2020, at a CAGR of 30.7%

Sep 21, 2016

The factors which are driving the vertical farming market include need for high quality food with no use of pesticides, less dependency on the weather, increasing urban population, and need for year round production. The largest market in the functional device segment is lighting market owing to the high acceptance of LEDs to replace traditional lighting. LEDs have been developed which provide optimum electromagnetic spectrum for photosynthesis, consume less energy, and have minimal heat signatures which keeps the energy requirement for temperature maintenance at a minimum.

Download Free PDF Brochure @http://www.marketsandmarkets.com/pdfdownload.asp?id=221795343

The vertical farming market is estimated to reach USD 3.88 billion by 2020, at a CAGR of 30.7% between 2015 and 2020.

Lighting functional device expected to lead the vertical farming market

Lighting as a functional device, in terms of value, is expected to hold the largest share of the vertical farming market by 2020. The traditional lighting system is being replaced by LED lighting system which is more efficient, emits electromagnetic spectrum ideal for photosynthesis and generates low heat. The increased acceptance of LED lighting system by end users is driving the growth of this market.

Hydroponics as a growth mechanism segment dominates the vertical farming market

The market for hydroponics as a growth mechanism is expected to be the largest between 2015 and 2020. This is mainly because of the benefits associated with it such as quicker growth, faster harvest, higher yield, and low nutrient wastage as mineral nutrients are dissolved in water and are fed directly to a plant’s root system without any involvement of soil.

APAC expected to hold the largest market share and grow during the forecast period

The APAC vertical farming market is expected to hold the largest share by 2020 owing to major driving forces such as growth in urban population, less availability of cultivable land, government initiatives, and demand for food with low impact on environment, the vertical farming market is growing in this region.

Global Vertical Farming Market, by Functional Device

- Lighting

- Hydroponic Components

- Climate Control

- Sensors

Global Vertical Farming Market, by Growth Mechanism

- Aeroponics

- Hydroponics

- Others

This research report categorizes the global vertical farming market based on functional devices, growth mechanism, and regions. This report describes the drivers, restraints, opportunities, and challenges with respect to the vertical farming market. The Porter’s five forces analysis has been included in the report with a description of each of its forces and their respective impact on the vertical farming market.

Major players involved in the development of vertical farming market Aerofarms (U.S.), FarmedHere (U.S.) Koninklijke Philips N.V (The Netherlands), Illumitex Inc. (U.S.), Sky Greens (Singapore), and others.

Independence LED Lighting

LED Grow Light Plant Growth Time Lapse For Basil With Aquaponics.

Inside Look: Independence LED Lighting Creates Better Produce!

Next-Generation Food Supply! See this time-lapse video showing 30 days growth in the controlled environment under Independence LED lighting. The LED Grow lighting creates a heavier and leafier product, which in this case is basil.

To view state-of-the art Horticulture LED Lighting for advanced Agriculture learn more here: http://independenceled.com/led-grow-lights/

LED Grow Lights can dramatically change the economics of indoor framing for warehouse and greenhouse facilities. Independence LED Lighting is ideal for Horticulture LED Lighting that advanced Agriculture LED Lighting for Indoor Farming such as the production of cost-effective Indoor Vegetables at Grow Operations.

Since LED lighting for commercial farming is “green” and on the rise, we welcome content submission such as LED grow light videos, LED grow lights photographs, and LED grow light production case studies.

Submit LED horticulture and LED agriculture content here via: Contact GREENandSAVE

Programming Sun and Rain: Students Run an Indoor Farm at School by Computer or Mobile App

High-school students grow an acre’s worth of vegetables in an old shipping container that’s been transformed into a computer-controlled hydroponic farm.

Green beans and other vegetables growing in the computer-controlled climate of a hydroponic farm in an old shipping container at Boston Latin School. Students monitor and control it all, on site or with a mobile app.

BOSTON – On the cramped urban campus of Boston Latin School, high-school students grow an acre’s worth of vegetables in an old shipping container that’s been transformed into a computer-controlled hydroponic farm. Using a wall-mounted keyboard or a mobile app, the student farmers can monitor their crops, tweak the climate, make it rain and schedule every ultraviolet sunrise.

In a few decades, nine billion people will crowd our planet, and the challenge of sustainably feeding everybody has sparked a boom in high-tech farming that is now budding up in schools. These farms offer hands-on learning about everything from plant physiology to computer science, along with insights into the complexities and controversies of sustainability. The school farms are also incubators, joining a larger online community of farm hackers.

“We are constantly experimenting,” said Catherine Arnold, a Boston Latin history teacher who oversees the environmental club that runs the farm as an extracurricular activity. It was built by a Boston startup called Freight Farms, which “upcycles” discarded shipping containers into “Leafy Green Machines” for small-scale growers and restaurants, as well as a dozen schools and colleges.

“My students can collect data on the farm from anywhere, whenever they want to.”

Graeme Marcoux, of Salem, Mass., who teaches a high school vocational course in hydroponics and aquaculture

The latest version of a freight farm costs $82,000. Boston Latin has a cheaper, earlier version, paid for with a green-schools grant. The students have been giving their food away but plan to sell produce to parents and neighbors this year, to cover the annual cost of seeds, nutrients and other supplies.

On a recent morning, Arnold showed off rows of spinach, peppers, tomatoes, lettuces, green beans and herbs hanging below drip irrigation that was bathing the roots in a recirculating mix of water and nutrients. The plants grew out of a recycled plastic mesh rather than soil and were lit by thin strips of LED lights.

When the school’s farm opened in 2014, Freight Farms staffers taught students about crops that have a proven hydroponic track record and their preferred mixes of temperature, nutrients, moisture and other factors. But Arnold said the real learning comes from trying new things.

“They never said you can grow green beans, but we have two varieties,” Arnold said. “This year, we’re going to try carrots and turnips. Anything the students want to try, we’re going see what happens.”

A video camera and sensors send real-time data about the growing environment to a computer that triggers farm systems set to schedules and thresholds (such as carbon dioxide or nitrogen levels). Students monitor and control it all, on site or with a mobile app. According to Graeme Marcoux, a high-school environmental and marine science teacher in Salem, Massachusetts, whose school set up a freight farm last spring, the remote access is essential, because only so many students can work inside a 320-square-foot box, and because farming doesn’t stop when the bell rings.

“My students can collect data on the farm from anywhere, whenever they want to,” said Marcoux, who teaches a vocational course (worth one science credit) in hydroponics and aquaculture.

Besides passing on technical knowhow, Marcoux encourages class debates about food sustainability. The many high-tech automated “vertical farms” popping up in cities around the world have a shared mission of growing more food locally, while using a lot less land and water than conventional farms. Being indoors means no pesticides, and their closed systems mean they don’t poison waterways with fertilizer runoff.

“To imagine you could help feed people with this computer was amazing to these kids. Most of them don’t think about technology and food going together, when clearly they do, even in traditional farming.”

Will Borden, director of academic technology, Shady Hill School, Cambridge, Massachusetts

But critics say that indoor farms are energy hogs. A farm like the one at Boston Latin, for instance, uses enough energy to power about two and a half American households. Of course, conventional agriculture also has many hidden energy costs, from shipping food, refrigerating storage facilities, manufacturing and operating massive farm equipment, and moving and treating all that irrigation water. Plus, rapid gains in LED efficiency and renewable energy will help shrink the carbon footprint of indoor farms.

“It’s a great debate to have with the students, because by the end of that debate everybody has a much deeper sense of what actually makes something sustainable,” said Marcoux.

The Freight Farm app links to a repository of articles about everything from crop scheduling to food safety. There’s also a Facebook group of freight farmers who are a ready source of ideas and advice on topics such as how to deal with tiny spots on your lettuce or how best to keep the humidity under control.

The potential of networked farmers swapping expertise and experimental results – call it crowdsourcing crops – is also at the heart of OpenAg, an initiative of MIT’s Media Lab, led by research scientist Caleb Harper. In 2015, the OpenAg group gave a handful of local schools prototypes of their “personal food computers,” which are tabletop hydroponic farms that users program with “climate recipes.” Every recipe, as well as the user-interface code, is open-source and posted online for use by a global community of green-thumbed hackers.

One of the early food-computer recipients was the Shady Hill School, a private preK-8 academy not far from MIT in Cambridge, where students grew basil, sage and various leafy greens.

Every grade had some access to the food computer. The first-graders, for instance, featured it in their “farm to table” unit, alongside food grown in an outdoor garden.

James O’Brien, a Connecticut high school senior, built and programmed his own “food computer” after watching a TED talk on YouTube; then he demonstrated the computer and the lettuce he grew with it to middle schoolers at a local summer camp. Photo: Eileen O’Brien

“They could not only measure the plants, they could see and measure the growing roots,” said Will Borden, Shady Hill’s director of academic technology.

“To imagine you could help feed people with this computer was amazing to these kids,” he added. “Most of them don’t think about technology and food going together, when clearly they do, even in traditional farming.”

The food computers for the pilot schools came pre-assembled. But for everyone else, they were totally DIY, using downloadable step-by-step instructions. For example, James O’Brien, a senior at Staples High School in Westport, Connecticut, was inspired to build a food computer after watching a Caleb Harper TED talk on YouTube last summer.

On his own, O’Brien machined and assembled the parts, bought the sensors, wired them into a circuit board, and programmed the computer’s brain. He demonstrated his food computer and the lettuce he grew with it to middle school kids at a summer camp run at a local farm. In August, he started a nonprofit called Workshop Garden Technologies to create after-school programs for middle-school students using food computers.

OpenAg is now readying a more refined and user-friendly kit version of the food computer for a second round of school pilots planned for the spring. It will also be possible to program the “climate recipes” with a simpler, block-based coding language, such as Scratch (another Media Lab creation).

There will still be a strong DIY element, however. The idea is that lesson plans, like climate recipes, will be created, shared and improved upon by the community of school food-computer users.

“We want to include kids in a co-creation process, to let them play with the food computer and help us improve the engagement and experience of growing with it,” said Hildreth England, OpenAg’s program coordinator. “Kids are natural tinkerers. It’s a perfect fit.”

This story was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Read more about Blended Learning.

By Chris Berdick

BrightFarms Raises $30.1 Million to Set Up Futuristic Greenhouses Across the U.S.

On a mission to make all fresh fruit and vegetables locally!

Agriculture tech startup BrightFarms has raised $30.1 million in Series C funding to bring its high-tech greenhouses, and fresh produce, across the U.S.

The company is on a mission to make all fresh fruit and vegetables locally, rather than require them to be hauled from long distances or imported from overseas before they are sold at groceries.

Taking a page from the playbook of solar power providers in the U.S., BrightFarms offers customers a long-term, fixed rate on the salad greens and tomatoes it grows in its greenhouses to grocers.

BrightFarms-raised produce.

The startup’s CEO Paul Lightfoot explained that after BrightFarms locks in a “produce purchasing agreement,” it raises funds from various sources including economic development programs and different banks or equity firms to build a new greenhouse.

In effect, a big chunk of the company’s cost of goods is already committed revenue before they open up a greenhouse’s doors and start growing.

The new round of funding was led by Catalyst Investors, and joined by BrightFarms earlier backers WP Global Partners and NGEN.

Catalyst’s Tyler Newton said his firm backed BrightFarms largely due to its business model innovation and ability to “out-execute” other food producers in the U.S.

Consumers definitely want to buy groceries made by local businesses, and to help support jobs that pay a local living wage in their own back yard. According to research by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, local food sales totaled $12 billion in 2014 and are expected to grow to $20 billion by 2019.

A BrightFarms greenhouse that grows tomatoes and salad greens.

“Where the seasons don’t cooperate, we just didn’t have the option to buy local before. So that feels good. But when you taste a tomato or some arugula from BrightFarms, and compare it to something that’s been shipped from out West, there is an obvious taste advantage, too. That’s what grocers want,” Newton said.

BrightFarms is going after a huge market that doesn’t have a lot of competition outside of the states of California and Arizona, today.

America’s farms contribute $177.2 billion, or about 1 percent of the nation’s gross domestic product each year according to the most recent available calculations also from the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

And 90% of the salad greens consumed in the U.S. are produced in California and Arizona, then shipped across the country or exported out of it.

Other agriculture tech startups like AeroFarms or FreightFarms are building out indoor and container-based farms, in urban areas to meet rising consumer demands for locally-produced, and delicious fresh foods.

BrightFarms CEO Paul Lightfoot

But Lightfoot believes that his company’s greenhouses – which take advantage of natural sunlight, obviously—can prove more environmentally sustainable and cost-efficient than indoor farms, and produce more supply than container-based and rooftop farms.

He says that’s because BrightFarms controlled environment greenhouses don’t need to use as much electricity for grow lights and temperature controls as indoor farms. Both are significantly more water efficient than traditional farms, even those using precise irrigation systems.

So far, BrightFarms operates three greenhouses, each employing 25 full-time workers, in the greater Philadelphia, Washington D.C. and Chicago metro areas.

If drought conditions continue, Lightfoot said, the company could someday move into the “salad bowl” state of California, or other agricultural hubs, displacing traditional, and often water-intensive, farms.

But for now it will focus on metro areas where demand for fresh produce is high but there isn’t a lot of arable land or weather to support traditional farms.

BrightFarms’ customers and partners have so far included grocers like Kroger, Ahold USA, Wegmans and ShopRite.

Besides using the new Series C capital to build out additional greenhouses, Lightfoot says the company will explore new crops and is likely to start growing peppers and strawberries in the near future.

Featured Image: BrightFarms Inc.

By Lora Kolodny

Elon Musk’s Brother Aims to Revolutionize Urban Farming with Square Roots