Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

What the Heck Is… Vertical Farming?

Radical solutions are needed to keep up with our fast-growing world population.

Our weekly series What The Heck Is… sheds light on the strange unexplained acronyms and unfamiliar buzzwords that creep into our everyday lives.

Farming, something humans have been doing for thousands of years, is struggling to adapt to our modern world. Radical solutions are needed to keep up with our fast-growing world population.

What’s wrong with regular farming?

Firstly it’s expensive, both in financial cost and the cost of land required to grow food at scale.

It’s environmentally unfriendly, not just with chemicals and pesticides being poured into the ground, but also the fact that farms only generate a few harvests a year. During winter most of the world’s farmland is simply being wasted.

Plus farming is creating food in the places that we don’t really need it.

More than 50% of the world’s population lives in cities, and this will rise to 80% by 2050, but all the food is being created in rural areas because of the land required to grow at scale.

The result is that transport costs, the environmental impact of transporting this food, and the fact that 30% of all farmed food is wasted because it spoils before it can be eaten, make traditional farming a costly exercise.

So is there a better way?

What the heck is vertical farming?

As its name suggests, vertical farming is a new way of growing of food can be stacked vertically, rather than horizontally, and uses technology to solve the problems with traditional farming.

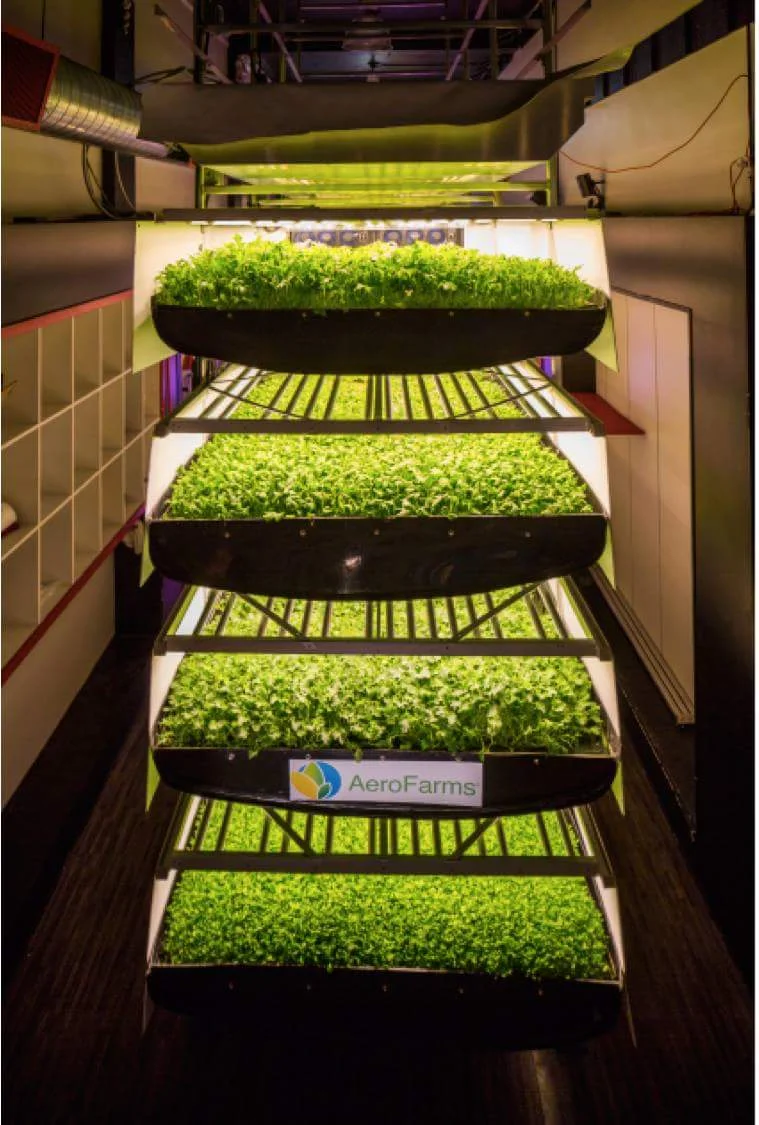

Think trays of crops stacked in warehouses, with their water, pesticides and even sunlight controlled by a computer, giving them exactly what they need to grow and dramatically boosting the quantity of food produced.

The theory suggests that these vertical farms could even be built inside skyscrapers or existing buildings, creating food where it is needed and reducing the environmental impact of farming.

We say theory, because at the moment that’s exactly what vertical farming is.

AeroFarm hasn't started vertically farming on an industrial scale, yet.

Putting theory into practice

Today there are several vertical farms in the early stages of construction.

In the US, Vertical Harvest based in Jackson, Wyoming, is up-and-running planning to vertically grow 100,000 pounds of vegetables every year.

If they achieve that goal it will offset 3% of the produce currently being shipped into the town.

But it’s early days and they have yet to prove that they can vertical farm this amount of food at such a scale.

AeroFarms in Newark, New Jersey, has even grander goals. The company plans to harvest 2m pounds of veg a year from their 69,000 sq ft warehouse, using 95% less water and 50% less fertiliser than a traditional farm… once production starts in September 2016.

The projects share two things in common:

Neither has proved that they can yet produce the quantity of food they promise, at an acceptable price and with a sustainable business model.

And both are supported by millions of dollars in venture capital investments and government subsidies.

What does it mean for your food shop?

If vertical farming works, the price you pay for food could fall – as transport costs disappear and farming becomes less wasteful – as we enter a new era of locally-sourced food.

Or, the price of your food could skyrocket – if the cost of the technology is passed onto shoppers, or if the efficiencies of vertical farming are never realised.

With millions being spent on vertical farming and dozens of vertical farms coming online over the next few months and years, it won’t be long until we discover if the food of the future will be grown in a warehouse.

Our weekly series What The Heck Is… exists to shed light on the strange unexplained acronyms and unfamiliar buzzwords that creep into our everyday lives.

By Oliver Smith

Old Steel Mill Will Soon Be World's Largest Vertical Farm

Stacks of leafy greens are sprouting inside an old brewery in New Jersey.

NEWARK, N.J. (AP) — Stacks of leafy greens are sprouting inside an old brewery in New Jersey.

On this Thursday, March 24, 2016, file photograph, New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie, center at podium, addresses a gathering at AeroFarms, a vertical farming operation in Newark, N.J. AeroFarms is now refurbishing an old steel mill in New Jersey and they say it will soon be the site of the world's largest indoor vertical farm. The company says their Newark facility, set to open in September, could produce 2 million pounds of food per year and help with farming land loss and long-term food shortages. (AP Photo/Mel Evans, File)

"What we do is we trick it," said David Rosenberg, co-founder and chief executive officer of AeroFarms. "We get it thinking that, if plants could think: 'All right, this is a good environment, it's time to grow now.'"

AeroFarms is one of several companies creating new ways to grow indoors year-round to solve problems like the drought out West, frost in the South or other unfavorable conditions affecting farmers. The company is in the process of building what an industry group says is the world's largest commercial vertical farm at the site of an old steel mill in New Jersey's largest city.

It will contain 12 layers of growth on 3½ acres, producing 2 million pounds of food per year. Production is set to begin next month.

"We want to help alleviate food deserts, which is a real problem in the United States and around the world," Rosenberg said. "So here, there are areas of Newark that are underprivileged, there is not enough economic development, aren't enough supermarkets. We put this farm in one of those areas."

The farm will be open to community members who want to buy the produce. It also plans to sell the food at local grocery stores.

Critics say the artificial lighting in vertical farms takes up a significant amount of energy that in turn creates carbon emissions.

"If we did decide we were going to grow all of our nation's vegetable crop in the vertical farming systems, the amount of space required, by my calculation, would be tens of thousands of Empire State Buildings," said Stan Cox, the research coordinator at The Land Institute, a nonprofit group that advocates sustainable agriculture.

"Instead of using free sunlight as we've always done to produce food, vertical farms are using light that has to be generated by a power plant somewhere, by electricity from a power plant somewhere, which is an unnecessary use of fuel and generation of carbon emissions."

Cox says that instead of moving food production into cities, the country's 350 million acres of farmland need to be made more sustainable.

But some growers feel agriculture must change to meet the future.

"We are at a major crisis here for our global food system," said Marc Oshima, a co-founder and chief marketing officer for AeroFarms. "We have an increasing population that by the year 2050 we need to feed 9 billion people. We have increasing urbanization."

Rosenberg also pointed out the speeded-up process.

"We grow a plant in about 16 days, what otherwise takes 30 days in the field," he said.

By TED SHAFFREY

Aug. 19, 2016 1:30 AM EDT

How to Apply for the USDA Microloan as an Upstart Farmer

So you’ve decided to start a farm.

by Amy Storey | Aug 18, 2016 | Farm & Business Planning

Freaked out about funding?

So you’ve decided to start a farm. You’re buzzing with excitement and anxiety about getting started, and maybe you’ve hit a few hitches in the planning process. You’re worried about getting the funding you need, and the world of financing can be overwhelming.

If this is you, then don’t worry! From grants and crowdfunding, to bootstrapping and loans, you have multiple options to fund your farm. One of those options is the USDA Microloan, a loan built specifically for unique startup farmers like yourself.

In this post, we’re going to explore how to apply for the USDA Microloan as an Upstart Farmer, including:

- why the microloan is a good option for small startup farmers

- what the process looks like

- tips on applying from a recent recipient

The benefits of the USDA Microloan

Farmers looking for money to jumpstart their farm (or farm expansion) should seriously consider the USDA’s microloan program. The microloan is built for alternative farmers growing niche crops or serving niche markets, including “those using hydroponic, aquaponic, organic and vertical growing methods.”

In face, I’ve spoken with two Upstart Farmers who have recently received the microloan – Carey Martin (who spoke about it in the “Funding Your Farm” course), and Chris Elliot.

The microloan was a great fit for Chris Elliott of Water Sprout Farm, an Upstart Farmer who runs a new indoor hydroponic farm.

We’ve noted before that starting a farm is becoming a more accessible goal to anyone with a few thousand dollars (the microloan provides up to 50K) and work ethic. These funding opportunities just add to that trend.

This is perfect for the Upstart Farmers, most of whom start small with specialty crops and/or specialty markets. Often, they are completely inexperienced in the field, but ready to sweep their communities off their feet with high quality local produce.

The USDA Microloan that Chris received is especially geared towards new and “underserved” farmers; in fact, over 70% of the loans provided have been given to just-starting farmers. This year, the FSA (Farm Service Agency, a part of the USDA) expanded the loan from operating costs to include building costs.

On top of that, the microloan typically has low interest rates. Chris’ loan run interest at 2.25%. “You can’t get that at a bank.”

The process: how to apply for the USDA Microloan

Of course, some loan applications can be tedious and overwhelming. Not so with the USDA Microloan. Chris says that because he already had his financial planning done before filling out the application (you should do this prior to seeking funding, by the way), filling the application only took an hour.

The office was able to answer all questions about completing the application process.

“They were good about answering questions, so don’t be afraid to ask,” advises Chris. “Unlike a bank that’s trying to determine whether or not they can make money off you, they’re really just trying to help farmers out.”

Many entrepreneur-focused institutions will have the same helpful attitude. “We found a bank out of Pittsburgh that does startup loans and they have a lot of ancillary benefits that really are helping out. I would imagine there are similar banks around the country. You pay more in interest but they actually will work with you [unlike some] traditional banks.”

After that, the application should only take a few weeks to process. (Factor in time for mailing, since many loan offices won’t take faxed forms.) the loan office will be able to give you more specific timelines depending on their staffing.

Challenges and tips for applying for the USDA Microloan

Although the loan application and process are streamlined for beginning farmers like you, there are several things that you can do to avoid hiccups and keep things moving. Chris had several insights for small Upstart Farmers.

1) Work to get loan managers the info they need.

Since loan managers aren’t usually familiar with vertical indoor growing, their questions might not be easy to answer, and the application might not be designed with questions suited to your farm. For instance, there might not be enough space to give a complete answer. Units might not be applicable (e.g.: “How many acres are you farming?”). The loan managers will want to know assets and debt – although you might not have any.

Chris says that this can be both good and bad.

“At a high level, we are a different breed than what the farm loan managers have ever experienced. They truly didn’t know what to do with me… This is a good and bad thing. They didn’t know enough to ask really tough questions, but they also didn’t know enough to figure out some easy ones on their own either.”

What to do: For assets and debt, ask if you can fill it out as though you had been in operation for a year. If they ask about the assets of the spouse who is not tied to the farm or the loan, just explain the situation and work with them to come up with a solution. The important thing here is that they have the information they need to make a good decision. So get it to them! Maybe there isn’t enough space for a financial plan. Summarize yours and send them the complete document on your own.

2) Turn everything in at once.

Make sure that you have gathered all of the documents and forms that you need, and turn it in at the same time. If you’re missing pieces, your application will be marked incomplete and after certain amount of time the application will be discontinued.

3) Know your numbers.

Depending on the farm manager, confidence in your financial and production planning can really sell them on your farm. This is when the pricing and planning information that you’ve worked on with Bright Agrotech is very convenient. If you’re planning a farm using ZipGrow, then you’re probably working on a Financial Plan and Analysis with one of our farm guides. (Not doing this yet? Here’s how to get started!)

Carey Martin noted that having someone look critically through your financial plan can be a huge asset, as they will spot holes and help you patch up rough spots.

4) Use Bright Agrotech and Upstart University as the required mentor and training certification.

“They wanted to make sure that you have some kind educational experience in farming, and be training or have a mentor. That was a hurdle I had to get through. I was actually able to use [Bright Agrotech] as a mentor and taking Upstart University; collecting those certificates worked as a legitimate training.”

5) Match your lease to your loan (and have an escape clause)

“One of the other hurdles that I came across was the length of the loan had to match the length of our lease of the warehouse. So we had to change our lease to a 7 year lease to match the 7 year loan. If that is the case across the board, farmers have to really try and negotiate a good escape clause in their lease in case things don’t work out.”

6) Be prepared for difficulty with additional liens

“One other issue was that USDA required to have the first lien on our equipment, so any additional lenders would have to take a 2nd lien, and a lot of the traditional banks did not want to do that. We had a hard time finding additional financing due to this. They won’t share the lien either, it has to be the first and only first.”

Is the USDA Microloan for you?

The microloan has served multiple starting farmers, and might be the best option for you.

If you want to look at some other funding options like grants and crowdfunding, go through the Funding Your Farm course on Upstart University.

And if the USDA Microloan is for you, you can get links to forms, instructions, and FAQ’s here.

Remember, financial planning should happen before funding!

Want information on starting a commercial farm? It can be tough to find. That’s why we’re walking aspiring farmers through the planning process in our Feasibility Workshop. In the online workshop, we’ll go through the process of creating your own in-depth feasibility study to help you make the business case for your future farm.

Indoor Farms Give Vacant Detroit Buildings New Life

Surplus of vacant buildings a boon for indoor farmers

Indoor Farms Give Vacant Detroit Buildings New Life

Breana Noble , The Detroit News 11:17 a.m. EDT August 16, 2016

Surplus of vacant buildings a boon for indoor farmers

Standing before a shelf of red incised lettuce, Artesian Farms Managing Partner Jeff Adams talks about the indoor vertical farming operation used to produce three types of lettuce and kale at the company in Detroit on Aug. 3, 2016. Brandy Baker, The Detroit New

Entrepreneurs are taking advantage of inexpensive former warehouses and factories in Detroit and transforming them for agricultural use to produce local foods.

There’s a growing movement of using vacant buildings and spaces to produce lettuce, basil and kale, and even experiment with fish farming — year-round.

And the city is considering regulations that could expand indoor agriculture even more.

“Fifteen, 20 years from now, we want people to say, ‘Of course they grow kale in that building,’ ” said Ron Reynolds, co-founder of Green Collar Foods Ltd. It built its first indoor-farming research hub in Eastern Market’s Shed 5 in 2015.

Green Collar Foods mists the bare roots of kale, cilantro and peppers using an aeroponics system under fluorescent lights in its 400-square-foot plastic-encased greenhouse. The system is built vertically, stacking plants on shelves to grow above each other. Supino Pizzeria in the Eastern Market buys its kale.

It’s one piece of Detroit’s growing urban agriculture scene. Although the city lost about a quarter of its population between 2000 and 2010, community gardens flourished from fewer than 100 in 2004 to around 1,400 today, according to Keep Growing Detroit.

In response, Detroit adopted a zoning ordinance in 2013 to legalize urban farming that was popping up all over the city. The urban agriculture ordinance, however, assumes indoor farming would be large-scale, said city planner Kathryn Underwood. To increase the zoning district, the City Planning Commission sent an amendment to the City Council for consideration that would take into account smaller operations. It is expected to vote on the proposal in the fall.

“(The amendment) recognizes (indoor farming) can happen at very large scales and very small scales,” Underwood said. “It will allow more of it to happen.”

There’s space for it. In 2014, Detroit had more than 78,000 vacant buildings, according to a blight task force survey.

That’s what Green Collar Foods found attractive about Detroit, co-founder Frank Gublo said. Several Detroit and Flint entrepreneurs are interested in working with Green Collar to create farms in 7,000-square-feet indoor spaces.

Green Collar’s Reynolds envisions franchised operations in unused buildings. “It creates a business in an area that is struggling to find businesses to locate in,” he said.

Less water, longer shelf life

Since 2013, at least three other indoor farms have opened in Detroit.

Jeff Adams started planting in 2015 at his Artesian Farms located inside a 7,500-square-foot former vacant warehouse in the Brightmoor district. He uses stacked growing beds and hydroponics to grow lettuce, kale and basil. The hydroponic system replaces soil with nutrient-filled water.

Adams said the kale sells competitively for around $4 for 5 ounces at retailers in Metro Detroit, including Busch’s and Whole Foods Market.

He said his farm has advantages over traditional growers. California farms use seven gallons of water to grow a bundle of lettuce, while his system uses three-tenths of a gallon. Growing locally also extends shelf life.

Artesian Farms, located in a 7,500-square-foot former warehouse in the Brightmoor district, uses stacked growing beds and hydroponics to grow lettuce, kale and basil. (Photo: Brandy Baker / The Detroit News)

“The food you’re eating right now, it’s seven to 10 days before it reaches Michigan,” Adams said. “(Artesian Farms’ produce) is from here to the market in a day, at most, 48 hours. ... It’s going to be much more flavorful and much more nutritional.”

Although the lights feeding his plants suck electricity, Adams is replacing them with purple LEDs, which use 40 percent less power.

That’s important for the future: Adams has five plant racks — one recently produced 95 pounds of lettuce in 36 square feet. By September, he expects to have 11 racks; by November, 26 racks; and in one year, 46 racks of lettuce, kale, spinach, arugula and bok choy. He plans to add five people to his team of two, including himself, by the end of the year — and another three when all stations are installed.

“The whole purpose of this was to employ people, and you can’t employ people if you’re going to be doing it four months out of the year,” Adams said. “If you want to farm all year-round, this is the way to do it.”

Start-up already plans to expand

Eden Urban Farms harvested its first batch of hydroponic lettuce earlier this year.

After researching indoor farmers in the Netherlands, CEO Kimberly Buffington started a pilot farm with four trays of plants, one producing 170 bundles of lettuce. Eden has grown herbs, lettuce, peppers and strawberries.

The company, which now resides in the basement of a business partner’s Milford home, will expand in the next two years to a 31,000-square-foot rental space at 1800 18th St. on the border of Corktown and Mexicantown. Eden has two employees and plans to hire five or six by year’s end. Once in full operation, Buffington expects to employ about 70. Her team is also developing a small-scale system for entrepreneurs.

Eden Urban Farms sells produce at markets and restaurants. Its basil goes at market price between $1.99 and $2.29 for three-quarter ounces, Buffington said. Herbs and peppers are the most profitable.

“We know that the model works,” she said. “If we want to be in business, we have to be competitive.”

Employing people was the goal

Central Detroit Christian Farm and Fishery opened in 2013, taking over a former food market at Second and Philadelphia when the owner donated it after struggling to sell the 3,200-square-foot facility.

The farm used a closed-loop aquaponic system. Tilapia swam in large tanks of water, and the fish-excrement wastewater was pumped through a dirt-and-earthworm filter. The water then flowed through sprinkler heads to the plants as a natural fertilizer, before cycling into the fish tanks again.

But like regular farming, indoor farming has challenges: A review six months ago found keeping the water at the ideal 75 degrees for the tilapia cost too much, said operations director Randy Walker. Fish had to sell at $8 per pound, above the $3 per pound Asian-raised tilapia at supermarkets.

“There’s a future in it, but the technology hasn’t caught up yet,” Walker said. “Everybody says they want it, but when it comes to putting the money down for it, they don’t buy local.”

The indoor farm now grows tomato and pepper starter plants under the lights formerly used for the aquaponic system to sell at Central Detroit Christian’s Peaches and Greens produce market.

“I think they found their stride,” Walker said. “We were employing people, that was the goal. We were educating people and producing food. We met our goal.”

bnoble@detroitnews.com

(313) 222-2032

Twitter: @RightandNoble

In Cold Wyoming Winters, A New Vertical Farm Keeps Fresh Produce Local

Now that Vertical Harvest is up and running, in frigid December, the tomatoes come from next door, instead of being trucked from Mexico

In Cold Wyoming Winters, A New Vertical Farm Keeps Fresh Produce Local

Now that Vertical Harvest is up and running, in frigid December, the tomatoes come from next door, instead of being trucked from Mexico.

Benjamin Graham 08.15.16 6:00 AM

Winters are notoriously harsh in Jackson, Wyoming, where temperatures can plunge far below zero and snowstorms regularly pummel the surrounding mountains. The conditions make for world-class skiing, but they aren’t necessarily conducive to growing heirloom tomatoes.

"The power here is using a small amount of land to serve a community."

As a result, the majority of vegetables consumed on dinner plates in this remote resort town have to be shipped in through steep canyons or over mountain passes, from locales as far afield as Florida, California, and Mexico. But a new vertical farming experiment in the heart of downtown is poised to turn that equation on its head, at least in part.

A group of architects, farmers, and municipal officials have come together to build a startup greenhouse, called Vertical Harvest, on a narrow strip of land next to a public parking garage. Conceived in 2009, the project took years of planning to get off the ground. Its first seeds were planted earlier this year.

If all goes according to plan, the three-story greenhouse will be harvesting more than 100,000 pounds of fresh, locally grown veggies annually. The founders of the greenhouse estimate it will offset 3% of the produce that currently has to be shipped into the valley. That kind of output, taking place on a tenth of an acre, would equate to the production of five acres of traditional agricultural land. "The power here is using a small amount of land to serve a community," says Vertical Harvest cofounder Nona Yehia.

By many accounts, it's working. On the top floor of the greenhouse, clusters of ruby red tomatoes already dangle from vines that hang near the ceiling. One story below, workers tend to trays of baby basil and sunflower cress basking in the warm glow of LED lights. In the background, bins of arugula are transported on conveyor belts across the width of the greenhouse and up and down its south-facing glass facade, feeding the plants on a combination of natural and artificial light.

Crops—which run the gamut from butterhead lettuce to sugar pea cress—are now being harvested each day and sold to grocery stores, local restaurants, and residents of the 10,000-person town.

Vertical Harvest is on the leading edge of a wave of multi-storied farming operations cropping up across the globe. In New Jersey, a company called AeroFarms is building a 70,000-square-foot farm in an old steel mill. Indoor farms have even taken hold in Alaska, where aspiring entrepreneurs are growing vegetables in shipping containers.

"The worst thing that could happen to Vertical Harvest is that it’s a one-off. The vision of the project would be that other communities could benefit from the work we’re doing here."

They all share a common goal: to produce more food on less land in a more controlled environment, all in a location that is closer to consumers.

"An outdoor farmer can control nothing," or at least very little, says Dickson Despommier, emeritus professor of public health and microbiology at Columbia University and author of the book The Vertical Farm: Feeding the World in the 21st Century and one of the most vocal proponents of vertical farming over the last decade.

Traditional farms are reliant on the whims of Mother Nature for things like temperature, precipitation, and sunlight. In vertical farms, nearly everything can be controlled, he says. That can translate to a 365-day growing season free of droughts and freezes.

At Vertical Harvest, for example, crops are grown hydroponically, meaning the roots of the plant sit in water infused with the nutrients needed to help plants grow. No soil is used, and the amount of water and fertilizer needed to grow nutritious crops is minuscule compared to traditional agriculture.

"You have the option of 95% survival of whatever you plant," Despommier says. "The best farms in America are 70%. Not only that, you can grow things year-round."

All of those benefits combine to create an industry that has some significant upside, and a few investors appear to be taking note. Partners in the AeroFarms project in New Jersey include Goldman Sachs and Prudential Financial.

But the potential profits of industrial-scale farming are not what the founders of Vertical Harvest are after. Instead, they are trying to build a model for community-based vertical farming, one that they believe will be replicable elsewhere.

You have the option of 95% survival of whatever you plant. The best farms in America are 70%."

The business is registered as a "low-profit" limited liability company, or L3C, meaning Vertical Harvest has stated social goals outside of simply maximizing income.

One of those is to help Jackson’s developmentally disabled residents by providing employment. Fifteen people with a variety of intellectual and physical disabilities share 140 hours of work each week. The greenhouse employs five additional people who oversee the small workforce and the hydroponic growing system.

Vertical Harvest also has been designed as a public space, at least partially. The ground floor serves as a community gathering area. On one side is a market, where anyone can walk in and buy fresh produce. Another section is quartered off as a "living classroom," where a small number of crops are grown for educational initiatives.

"The worst thing that could happen to Vertical Harvest is that it’s a one-off," Yehia says. "The vision of the project would be that other communities could benefit from the work we’re doing here."

The greenhouse was made possible through a partnership with the town of Jackson, which provided the land and backed a $1.5 million state grant that was eventually awarded to Vertical Harvest. As a result, the town owns the greenhouse structure, while Yehia operates the business. All told, the greenhouse cost $3.8 million, with the balance coming from investors, donations, and debt.

In land-scarce Jackson, the partnerships were integral to getting the project done. Ninety-seven percent of land in the county is public. The scarcity works to drive up prices, making the town’s contribution vital. To break even, Vertical Harvest plans to lean heavily on selling high-value "microgreens," which are harvested just days after seeding and are highly sought after by fine-dining chefs.

But before city council members agreed to the project, they wanted some questions answered about energy efficiency. They weren’t convinced that growing tomatoes in winter would be less carbon-intensive than trucking them in from far away. They also had questions about the business model. If Vertical Harvest were to go under, the town would be stuck owning a greenhouse.

So, near the onset of the project, Yehia and her partners had a feasibility study done that found a greenhouse could work in Jackson. They also hired a specialty engineering firm, Larssen Ltd., which has built profitable greenhouses in other extreme climes, such as Siberia. All five members of the city council ended up getting on board.

"In terms of preparing the world for climate change, it’s a good way to make cities more resilient."

In the end, Yehia and other vertical farming experts say they don’t necessarily view the industry as a silver bullet for the future of global food production. At this point, growing certain things, such as fruit trees or root vegetables, just isn’t economical in vertical farms, says Andrew Blume, North America regional manager of the Association for Vertical Farming.

But he and others do view the nascent practice as a sustainable way to supplement the existing food industry. "In terms of preparing the world for climate change, it’s a good way to make cities more resilient," Blume says. It helps democratize the food production process by bringing it closer to consumers.

Vertical farms also help create green jobs and promote food transparency. When a new greenhouse pops up in a community, residents are apt to learn more about what they are eating and where it comes from. That, in turn, says Blume, can help communities become healthier.

Benjamin Graham is a writer in Jackson, Wyoming.

Futuristic Japanese Indoor Vertical Farm Produces 12,000 Heads of Lettuce a Day with LED Lighting

Philips Lighting has launched the latest in its indoor vertical farming experiments, with trials at two Japanese facilities.

Philips Lighting has launched the latest in its indoor vertical farming experiments, with trials at two Japanese facilities—with one growing 12,000 heads of lettuce a day under horticultural LED lighting technology. Indoor farming is a growing trend in urban centers, where farmland is not prevalent. A wide variety of herbs and greens can be cultivated in climate-controlled environments under LED lighting, for an energy efficient food production method that connects local folks to freshly grown produce.

The two trial farms in Japan demonstrate the awesome potential of indoor urban farming efforts.

Innovatus’ Fuji Farm in Shizuoka Prefecture is an almost 20,000 square foot facility where farmers have spent the past 14 months growing five different varieties of lettuce. Now, the farm harvests 12,000 heads a day that are mainly frilled lettuce, green leaf, and romaine. The efficient vertical farm setup saves not only land and energy, but also water, and Fuji Farm’s harvests can be picked, packaged, and on store shelves in under two hours.

At Delicious Cook’s urban farm in Narashino City in the Chiba Prefecture, an enticing selection of edible herbs are grown under Philips LED lighting. There, farmers have been experimenting with less common varieties of herbs, including edible chrysanthemums and coriander, with great success. In a space smaller than many urban apartments (around 860 square feet), the farm recently completed a 10-month trial in which these unusual herbs were grown under Philips GreenPower LED system. The resulting crops will be used in the company’s processed food products.

One of the key advantages of Philips Lighting horticultural LED systems is the “recipes” used to cultivate specific crops. Farmers are able to set the precise combinations of light, temperature, and humidity level for optimal production of each type of plant. Philips makes the job of urban farmers even easier by developing specific light recipes for various crops, which dictate light spectrum, intensity, illumination moment, uniformity, and positioning. Using this approach, crop yields skyrocket, with consistent quality and flavor, all without daylight.

Images via Philips Lighting

By Cat DiStasio

Indoor Farms of America Announces Manufacturing License Agreement For GrowTrucks Product Line, Multiple Sales

"We are excited to team with Tiger Corner Farms as we expand our reach into the Southeast region of the United States"

Indoor Farms of America Announces Manufacturing License Agreement For GrowTrucks Product Line, Multiple Sales

News provided by

Aug 08, 2016, 13:36

LAS VEGAS, Aug. 8, 2016 /PRNewswire/ -- Indoor Farms of America is very pleased to announce today the completion of a licensing agreement with Tiger Corner Farms, located in Charleston, South Carolina for assembly of their GrowTrucks product line covering the Southeast region of the U.S. to facilitate the growing demand for the GrowTrucks containerized vertical aeroponic farms.

"We are excited to team with Tiger Corner Farms as we expand our reach into the Southeast region of the United States," stated David Martin, CEO of Indoor Farms of America. "After purchasing a container farm from us this Spring, they realized our innovation in indoor agriculture is far ahead of anything else in the marketplace, and wanted to expand their relationship with us, and so we reached agreement for Tiger Corner Farms to be our exclusive representative in 7 states along the eastern seaboard, from Virginia to Florida, and including Alabama and Tennessee."

Don Taylor, founder of Tiger Corner Farms, with a long career in logistics management and innovative software development, stated: "When we met Dave at Indoor AgCon in April, we knew right away the vertical aeroponic technology and overall farm platform developed by Dave and Ron had fantastic potential. A visit to their showroom in Las Vegas sealed it for us."

"Part of our plans include bringing ultra fresh, natural and locally grown produce into the neighborhoods that need it most here in our region," says Stefanie Swackhamer, general manager at Tiger Corner Farms. "Dave is working closely with us to ensure our farm becomes a success, and we are excited to be the new manufacturing partner to serve this region with this amazing farming equipment."

The first GrowTruck to hit South Carolina was the Wheelchair Accessible model, which holds 4,550 plants in a 40' container, and is fully operable by someone in a wheelchair. According to Ron Evans, President of Indoor Farms of America, "This was an emotional one for us. We know that thousands of people can benefit from having the ability to be actively involved in running a commercial farm, who never before would have had this type of opportunity."

Part of the commitment from Tiger Corner Farms was the purchase of 10 farms to get started in the region. "We believe there is a real need for these containerized farm platforms in many areas that simply do not get truly fresh produce, especially locally grown produce, on anything resembling a regular basis, and we are gearing up to make it happen," says Don Taylor. Taylor added, "These farms are really pretty easy to operate, and have growing capacity that makes economic sense, above anything else on the market."

"This alliance with quality folks such as Don and his team add to our overall build capacity to satisfy growing demand for our products, and reduce shipping costs to customers in a large region, which makes sense for us as we execute on our plans to bring the best end to end indoor farm solutions to the marketplace across the U.S. and internationally," added Martin.

Indoor Farms of America Contact:

David W. Martin, CEO | Email | IndoorFarmsAmerica.com

4020 W. Ali Baba Lane, Ste. BLas Vegas, NV 89118

(702) 664-1236or (888) 603-7866

Southeast Regional Representative:

Tiger Corner Farms

Stefanie Swackhamer, General Manager

Email | Phone: 843-323-6521

Could This Glass-Enclosed Farm/Condo Grow on Rem Koolhaas’ High Line Site?

From multidisciplinary architectural firm Weston Baker Creative comes this vision of glass, grass and sass in the form of a mixed-use high-rise springing from the Rem Koolhaas parcel along Tenth Avenue and West 18th Street on banks of the High Line

Could This Glass-Enclosed Farm/Condo Grow on Rem Koolhaas’ High Line Site?

Posted On Fri, August 5, 2016 By Michelle Cohen

From multidisciplinary architectural firm Weston Baker Creative comes this vision of glass, grass and sass in the form of a mixed-use high-rise springing from the Rem Koolhaas parcel along Tenth Avenue and West 18th Street on banks of the High Line. As CityRealty reported, the mixed-use concept would include residences, an art gallery and ten levels of indoor farming terraces. The 12-story structure would rise from a grassy plaza, with the tower’s concrete base meeting the High Line walkway in a full-floor, glass-enclosed gallery that would sit at eye level with the park.

The tower’s form is driven by sunlight, similar to Jeanne Gang‘s “Solar Carve Tower” planned for the Meatpacking District. From Weston Baker’s page: “As the sun comes across the sky to the west, the building twists to evenly distribute daylight throughout the day.” On the southern elevation an enclosed atrium would hold 10 sets of farming terraces on view for High Line visitors and accessible to building residents. There would also be a public “observation garden” on the top floor and an art gallery on the second floor, also accessible from the High Line.

Given the building’s fantastical form, West Chelsea‘s zoning guidelines, the amount of public space and the fact the the High Line prohibits direct access to adjacent private properties, the building likely exists only in the conceptual realm at the moment, but it’s definitely a space to watch. In 2015, the New York Post reported that Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas of Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA) will design a project at the site, which had been recently purchased by luxury development firm Related Companies.

New York Buildings With Communal Gardens

Now some new developments are offering residents space in on-site gardens...

Joining a community garden or growing herbs on your kitchen windowsill are two tried-and-true methods for New York apartment dwellers to keep their green thumbs active. Now some new developments are offering residents space in on-site gardens, and at least one has created a farm on the building’s property.

Hunters Point South, an affordable housing complex in Long Island City, Queens, has a 2,300-square-foot communal garden, right, that is tended by about 100 tenants who are members of a garden club. The garden is run by GrowNYC. Steve Freihon

At Hunters Point South, an affordable housing complex in Long Island City, Queens, a garden club with about 100 members helps tend a 2,300-square-foot communal garden on the 14th floor of one of two buildings. More than 300 people applied for garden club membership last year, according to Joanna Rose, a spokeswoman for the Related Companies, one of the development partners. Those not chosen in a lottery have been placed on a waiting list.

The garden is run by GrowNYC, a nonprofit organization that builds and supports community and school gardens, among other programs. The garden is governed like many others in the city: Members must volunteer a certain number of hours per season and attend workshops in order to maintain membership and receive permission to work in the garden.

So far this summer, there has been a bountiful harvest of strawberries, string beans, Swiss chard and arugula, according to Gerard Lordahl, a director of GrowNYC who has helped shape the garden club. “I wouldn’t be surprised if we get over 1,000 pounds of produce by the end of the season,” he said.

GrowNYC will run the garden through the 2017 gardening season and then hand off the operation to garden club members who will elect a board and adopt bylaws. With so many residents on the waiting list, the club is exploring expanding its offerings to incorporate activities for nonmembers, like educational programs for children with an emphasis on where their food comes from, Mr. Lordahl said.

The harvest is shared by members, and some of the produce is sold for $12 a box to other residents.

The garden has a solar oven that has been used to make kale chips and sun-dried tomatoes, and parents have been enticing their children to drink smoothies by pedaling the bicycle blender, Mr. Lordahl said.

The Ironstate Development Company, the developer behind the Urby Staten Island rental apartments on the North Shore, has a for-profit farm atop an underground garage on the seven-acre property. David Barry, the president of Ironstate, said the urban farm was incorporated into the plans after designers thought about building common spaces that people might use and benefit from.

The developers invited Zaro Bates and Asher Landes, the partners of Empress Green, an urban farm operator and consultancy, to run the farm. The two started building the 4,500-square-foot farm and a rooftop apiary while the development was still under construction. Residents can volunteer to get their hands dirty if they like. These days, a variety of vegetables and herbs have been harvested and sold at the Bodega, the development’s ground-floor market.

Brendan Costello, Urby’s chef-in-residence, uses the farm’s produce in weekly cooking demonstrations and to make free treats for residents. Mr. Costello said his favorite dish so far was fried radish cakes with avocado sauce.

A weekend farm stand, which is open to the public, is growing in popularity, Mr. Landes said.

Some vegetables will be sold to a future Coffeed cafe that plans to incorporate the produce into light bites.

At 550 Vanderbilt in the Pacific Park complex in Brooklyn, a 3,500-square-foot communal garden will be installed before residents move in at the end of the year. Greenland Forest City Partners, the development partnership behind the condominium building, will even see that seeds are started for the 2017 growing season. But it will be left to the incoming condominium board to determine how to maintain the eighth-floor space.

The board might decide to assign individual plots to residents or keep the garden’s bounty communal, said Susi Yu, an executive vice president of Forest City Ratner. Inviting a restaurateur to come in as a consultant or to give cooking classes might also be an option, she said.

“Our garden is designed to be a gathering space,” said Ms. Yu, noting it will include a big communal table for residents to use. “Building nature into the daily life of residents was a deliberate decision.”

By Kaya Laterman

Countertop Nanofarming? New Kitchen Device Grows Fresh Produce Indoors

A new device could bring fresh, homegrown produce directly to the kitchen.

Countertop Nanofarming? New Kitchen Device Grows Fresh Produce Indoors

A new device could bring fresh, homegrown produce directly to the kitchen.

The Replantable Nanofarm is an at-home agriculture kit designed for people who want freshly-picked produce but don't have the time and space for a garden.

As the name suggests, Replantable is a small, indoor farm, about the size of a mini-fridge, which could easily be placed on a kitchen countertop. The set is composed of a grow cabinet, water tray, plant pad and harvest light. And with a few steps, homeowners could grow their crops in the machine.

"The nanofarm started off as a simple hydroponics system where users plant seeds and add fertilizer manually. We chose hydroponics because it is convenient to do indoors and allows us to avoid the use of pesticides," Ruwan Subasinghe, co-founder of the Atlanta, Georgia-based company, told Digital Trends.

"As we made prototypes and sent models to early customers, the consistent feedback was that it was still too much work. We started developing technology that would take more and more of the work off the user's hands. Where we ended up is the 'set and forget' system we're bringing into production."

The device simplifies farming into three steps: setting the number of weeks required to grow the crops, pressing the "Start" button, and pressing the "Harvest" button. Anyone could use the device, especially those without gardening experience, Subasinghe said.

The Replantable Nanofarm is made of powder-coated steel and natural wood, and its doors are corrosion-resistant and made of marine-grade aluminum to make sure that they won't break or rust. The device is also fitted with a smoked glass door to keep most of the light inside the device, and features a "whisper-quiet" ventilation system that pumps carbon dioxide to the crops while venting oxygen-rich air into the home.

The device has been under beta testing and will be launched via a Kickstarter campaign on Aug. 22, where it will be priced at $350.

Farming on the moon and meat grown in a lab. Six thoughts on the future of food.

As a technologist turned restaurateur, Kimbal Musk thinks daily about the future of food.

As a technologist turned restaurateur, Kimbal Musk thinks daily about the future of food.

Kimbal Musk (Courtesy of The Kitchen)

His own collection of restaurants, named The Kitchen and Next Door, aim to shake up food distribution by sourcing ingredients locally and providing fresh, natural food at sensible prices. His company, also called The Kitchen, builds hundreds of school gardens to teach children in low-income communities about healthy eating.

“No one wins in the industrial food system,” Musk said. “It’s awful at the individual level, and at the economic and community level.”

Musk’s last name should sound familiar. His older brother, Elon Musk, is the founder and chief executive behind technology firms Tesla and SpaceX. Musk sits on the boards of both of his brother’s companies, as well as the board of Mexican fast-casual chain, Chipotle. His career, in many ways, straddles the line between food and technology. (He and Elon originally made their fortune founding Zip2, a company that Compaq acquired in 1999.)

Musk spoke about his business ventures and restoring trust in the food industry last month at the World Future Society’s annual summit. Innovations caught up with him after the conference to pick his brain further. Here are six of Musk’s bold thoughts on the future of our food.

1. Vertical farming is poised for prime time — and outer space.

There is no question that Musk is a strong proponent of vertical farming, by which crops are grown in tall stacks under LED lights inside massive indoor facilities. The practice is being driven in large part by a desire to grow produce locally and thereby eliminate the need to ship items long distances. It would allow major urban centers, such as New York City or Chicago, to eat local fruits and vegetables during all four seasons. Musk said that 2015 marked the first year when vertical farming companies could sell produce at a profit, meaning the declining cost of the technology makes the practice feasible for the mass market. And when future generations eventually inhabit the moon, vertical farming may be how people eat fruits and veggies there. At least that’s what Musk told the audience of futurists late last month.

Lettuce farming in a modern hydroponic vertical farm, which uses only 1 percent of water a normal soil based farm would require.

2. Farming could soon be cool again.

Young Americans have not been bullish on careers in farming since roughly the Great Depression. Family farms have declined precipitously and corporate farms have been on the rise in the last 80 years, as The Washington Post previously reported. Musk sees an opportunity for that to change. The U.S. Department of Agriculture will offer $20 million each year in grants for new farmers until at least 2018. And thanks to aforementioned vertical farming, budding green thumbs need not move to rural communities to break into the agriculture business. For those who do desire the great outdoors, however, there may soon be ample land up for grabs. The average age of farm owners continues to increase, and more farmland will become available as those individuals lay down their shovels. “There will be an avalanche of supply of farmland over the next 5 to 10 years, or maybe at the latest 15 years,” Musk said. “It’s going to be a very exciting time in farming.”

3. The next million-dollar ideas will come from disrupting the food industry.

Of course, farming is just one end of the global food supply chain. Musk believes the industry is ripe for disruption all along the pipeline, from those who process ingredients into products to those who distribute them to restaurants that serve them. He compared it to the Internet in the 1990s. “You don’t know exactly what opportunity is in front of you, but you want to be in that industry. You want to be at the start of that wave,” Musk said. “My advice for any entrepreneur or innovator is to get into the food industry in some form so you have a front-row seat to what’s going on.” Successful entrepreneurs in the food business are also more likely to hail from Minneapolis or Memphis than Silicon Valley or New York, Musk added. America’s heartland and its food consumption habits more accurately reflect the country at large. “If you’re a vegan fast food joint in LA, you just don’t speak the same language as the heartland,” Musk said.

4. Trust in the food system requires greater transparency.

Musk focused much of his World Future Summit speech on trust and the idea that we no longer have much in our food. Whether it’s genetically modified produce or hard-to-pronounce chemical ingredients, Musk said that people often aren’t aware of what they’re eating or how it was made. In a world where vegetables are grown in warehouses and meat is made of plants (more on this in a minute), Musk said that building trust through transparency is absolutely crucial. “The problem with industrial food is zero transparency. The system thrives on the fact that there is no transparency,” Musk said. He hopes the next generation of food growers and manufacturers take a different approach. “If I were these guys, I would be thinking very much about transparency. What is the true impact of their product? What is the true nutrition of their product? Even if they have to use some futuristic ingredient, for lack of a better word, they’re very clear about what it is rather than hiding it from the consumer.”

5. Community impact requires entrepreneurs to go deep, not broad.

You don’t often meet entrepreneurs who think local. Take Musk’s older brother, who is trying to send people into space and eliminate their need to drive cars here on Earth. Musk said he, too, had a mind for global domination as a tech entrepreneur, but the same broad approach does not work in food. Shopping for groceries and dining at restaurants are still inherently local, and having an impact on the food people choose to consume has to be local as well. That’s why when Musk builds school gardens in a city, he constructs dozens of them at a time. He’s slated to open 50 in Pittsburgh and 100 in Indianapolis, for example. “When I look at a community and think about how we can bring this community to a real-food culture and get them thriving again, you have to go deep,” he said.

6. Our taste for meat will force us to look beyond animals.

Can a burger made from pea protein replace meat?

The beyond burger from Beyond Meat aims to replicate the texture, color and taste of a beef burger. (Jayne Orenstein, Joe Yonan/The Washington Post)

Successful efforts have been made to engineer meat in a laboratory or replicate it using plant-based ingredients. These aren’t frozen veggie burgers; we’re talking about an innovation beyond that. “Meat” that doesn’t come from cows, pigs and chickens could one day be more widely eaten, a shift that both animal welfare advocates and environmentalists would likely celebrate. After all, the increasing number of livestock that is necessary to sate the world population’s meat consumption has had a well-documented, negative impact on the environment. For his part, Musk is much more enthusiastic about plant-based meat products, questioning whether the lab-grown variety is something consumers will ever trust. He also says simply eating less meat is one path forward. “I am a fan of less and better meat rather than replacing meat,” he said. “That’s just me personally.”

Read more from The Washington Post’s Innovations section.

By Steven Overly

UK’s First Vertical Farm To Be Built In Scotland

They have the ability to grow crops in quick time, without the need for vast amounts of land, water or sunshine

UK’s First Vertical Farm To Be Built In Scotland

ALISON CAMPSIE

They have the ability to grow crops in quick time, without the need for vast amounts of land, water or sunshine.

Now the first vertical farm of its type in the UK is to be built in Scotland following a £2.5 million investment from the James Hutton Institute and Intelligent Growth Solutions (IGS).

Lettuce, baby leaf vegetables and microgreens are to be planted in the high-tech growing house near Invergowrie as part of a research project into how vertical farms can best produce crops for Scotland and beyond.

The method is being championed around the world –particularly in urban centres in the US as a way to grow food in small spaces without the need to transport the produce over long distances.

Crops are typically grown under LED lights with hydroponic systems using minimum water and no soil.

IGS predicts costs – such as those generated by lighting –will fall quickly to allow crops such as strawberries and tomatoes to be grown.

Henry Aykroyd, chief executive of IGS with 30 years experience in large-scale farming in the UK, Eastern Europe and California, said: “Our mission is to enable our customers to be the lowest cost producers by growing local globally, with better quality and saving natural resources. The process uses little water, no pesticides, can enhance taste and is consistent all year round.”

The Invergowrie farm will be the first in the UK to be built using automated towers which can respond to peaks and troughs of energy use.

Mr Aykroyd said: “Our real-time software can ‘grab’ power when the grid has surplus power and ‘shut down’ at peak times.

“Our automated growth towers are fully programmable to suit many diverse crops, and provide smart solutions to automation, power management and lighting issues,” he added.

Perth and Kinross Council has granted approval for the project with a 10-year lease now signed by the James Hutton Institute and IGS.

Professor Colin Campbell, Chief Executive of the James Hutton Institute, said: “We are doing more research with such innovative companies in the private sector and this example combines our knowledge of plant science and specialised infrastructure to work with others whose vision is aligned to help solve the challenges around long-term food security.”

FreshBox Farms Now Non-GMO Project Certified

FreshBox Farms greens are now non-GMO certified.

MILLIS — FreshBox Farms greens are now non-GMO certified.

The vertical farm’s entire product line, while always free of genetically modified organisms, is now Non-GMO Project verified. The Non-GMO Project supports providing consumers with clearly labeled non-GMO food and products, and is North America’s only independent verification for products made according to best practices for GMO avoidance.

FreshBox Farms uses controlled environment hydroponics to create perfect produce, thanks to the latest controlled environment agriculture technology. The growing system uses no soil, very little water, controlled light and a rigorously tested nutrient mix created by plant scientists on staff to produce the freshest, cleanest, tastiest produce possible.

Certification includes required ongoing testing of at-risk ingredients, rigorous traceability and segregation practices to ensure ingredient integrity and thorough reviews of ingredient specification sheets to determine the absence of GMO risk. Verification is maintained through an annual audit, along with on-site inspections for high-risk products. Product packaging will include the Non-GMO Project logo within a few weeks.

FreshBox Farms also recently announced a major expansion that will help the Massachusetts-based vertical farm stay on track to become one of the nation’s largest modular hydroponic growers. The sustainable hydroponic farm will increase its capacity by 70 percent, to about 40,000 square feet of indoor growing space.

The expansion, set to be completed in September, comes in response to growing demand through its new direct-to-consumer strategy via partnerships in the region.

How Chicago Became a Leader in Urban Agriculture

From the world’s largest rooftop garden to the country’s biggest indoor aquaponic farm, Chicago is leading the nation in urban food production. Here’s why this is happening

How Chicago Became a Leader in Urban Agriculture

From the world’s largest rooftop garden to the country’s biggest indoor aquaponic farm, Chicago is leading the nation in urban food production. Here’s why this is happening.

July 28, 2016

In the 1830s, when Chicago was becoming established as a city, a new motto was also created: “urbs in horto,” Latin for “city in a garden.”

Chicago became a city in a garden during World War II with the victory garden movement. With 250,000 home gardens and 1,500 community farms, Chicago led the nation as an example of successful urban food production.

Today, the city is still living up to its motto as it continues to be an innovative national leader in urban agriculture.

The Chicago Urban Agriculture Mapping Project has listed that there are over 800 growing sites in Chicago. These sites include school and community gardens, orchards, urban agriculture organizations, protected habitats, and more.

The city also boasts numerous urban agriculture startups, the world’s largest rooftop farm, and the nation’s largest indoor aquaponic farm in nearby Bedford Park.

Urban agriculture’s success in Chicago can be attributed to a number of factors including the amount of vacant space, progressive land zoning policies, an increased demand for locally grown food, and the city’s innovative, entrepreneurial spirit.

But prior to urban agriculture’s recent successes, pursuing agriculture in the city was still an idea that required testing.

In 2001, Harry Rhodes was starting to get involved with Growing Home, an organization built out of founder Les Brown’s vision of providing job training for the homeless through urban farming.

“At the time, people thought he was crazy,” Rhodes said. “We started doing the work in 2002 and found out very quickly that all the skeptics were wrong. Developing urban farms has a lot of benefits for a lot of people, and giving people a chance to grow and to work on farms is very transformational.”

At the time, Advocates for Urban Agriculture, an organization of individuals and other groups promoting urban farming, was also getting started. Only a handful of Chicago urban agriculture organizations, such as Growing Power and City Farm, existed at the time.

Billy Burdett, executive director of Advocates for Urban Agriculture, said he has seen “an exponential growth” in both the number and variety of urban agriculture projects in the city since he became involved with the organization.

In 2011, an amendment to the Chicago Zoning Ordinance was passed that defined community and urban gardens and allowed for community gardens to be up to 25,000 square feet in size.

Open space has been a key to urban agriculture’s success in Chicago. Whether it be rooftops, empty warehouses, or vacant lots, the city’s abundance of space has given entrepreneurs an opportunity to take over and create something green and productive.

“You don’t have (vacant land) in a city like New York or San Francisco,” Rhodes said. “Many people say vacant land is a detriment to community development, but it also can be seen as an asset.”

Vacant land was undoubtedly seen as an asset by Urban Canopy, an urban agriculture organization founded in 2011 that runs multiple growing spaces in the city.

“There’s a lower cost of entry to an industry when you can start growing stuff on land that is already there,” said Alberto Rincón, co-founder of Urban Canopy. “There’s just space to grow and to build.”

However, managing soil in the city can be a problem. Chicago’s soil can often be polluted with high levels of lead and metal from previous industries housed on the land. Rhodes said that in probably 90 percent of cases, farms have to build raised beds or growing areas, and that can result in high startup costs.

But it’s a cost of being in the city, which is why companies such as Gotham Greens and FarmedHere have taken their growing operations indoors and to rooftops to become a part of the wave of vertical farming — a market expected to reach almost $4 billion by 2020.

Being an urban farmer also has its advantages in having access to resources. Rhodes said the city of Chicago has been helpful in providing initial funding to startups, nonprofits, and urban farms. Programs such as the Good Food Business Accelerator have also helped entrepreneurs build their businesses.

“It’s been interesting to see the city slowly come around, and today they are fully in favor of urban agriculture,” Rhodes said.

Burdett said he attributes a lot of Chicago’s success to the community that has grown around urban agriculture and the increased demand for locally grown food.

“There’s been this broad awakening . . . where people are just really interested in supporting local and sustainable food production, and so there’s a pretty big demand out there,” Burdett said. “I don’t think that we have really even gotten close to meeting that demand. I think there’s a lot more growth to be done in the urban agriculture community.”

Meeting these demands bring its own set of challenges, but those in the community say they believe Chicago’s innovative spirit can help them get there.

Rincón said he is especially excited to see how engineers can make urban agriculture more tech-focused. Possible applications could include mobile apps providing services from urban farms — think Uber for composting — and using precision agriculture technology on smaller, urban farms.

But in order for companies to thrive, Rincón said urban agriculture needs to have support from pre-existing companies — and startups need to make sure they’ve built an argument that their idea is worth investment.

Creating sustainable business models will also be critical — Rhodes said this is “key for the growth of the industry” of urban agriculture and making Chicago a national leader for urban agriculture.

“I think (Chicago is) one of the leaders,” Rhodes said. “I’ve visited a lot of cities and I haven’t seen any that have more going on than Chicago.”

Burdett said he hopes that through the urban agriculture movement, the city can emulate its roots in the success of the victory garden movement.

“Our goal is to increase production so that we can get closer to the point where Chicago and other cities across the countries were, at the peak of the victory garden movement during World War II especially — 40 % of the nation’s produce was coming from these mostly small victory gardens,” he said. “We think there’s a huge amount of potential to meet the majority of this city’s produce needs.”

How Motorleaf Is Helping Automate Indoor Farming

The motorleaf system can be used in any type of indoor farming operation from greenhouses through to warehouses and at any size

How Motorleaf Is Helping Automate Indoor Farming

Editor’s Note: motorleaf is raising $750k in seed funding on AgFunder.

If you walk into the produce aisle at Price Chopper’s Market Bistro store in Latham, New York, you will be greeted with one of the first hydroponic tomato growing operations inside a grocery store.

Installed in the store when it was built in 2014, the hydroponic display has developed quite a following from local consumers who keenly report back on the progress of the tomato plants to the operator, Vermont Hydroponic Produce.

What they don’t realize is that Vermont Hydroponic Produce has a clear view of this operation without having to step foot into the store, because the operation is being monitored, and automated, by a technology platform developed by Canadian startup motorleaf.

Motorleaf has built a smart and automated indoor farming operating system, consisting of hardware devices and software analytics, to enable growers to capture data about their crops, learn what the crops need, and instruct existing equipment to answer those needs.

Price Chopper is using motorleaf’s HEART device, which collects air temperature, humidity, and lighting level data, and feeds into motorleaf’s intuitive software. The HEART device then connects to an operation’s lighting hardware and feeder pumps to start automating their use. Growers can receive custom alerts to any mobile device to find out about the changing conditions of their farm and can even connect webcams into the HEART so they can view the farm in real-time.

The HEART, one of 4 hardware units. Plug it in and it starts collecting Air Temp, Humidity, & Light Level data. Connect any lighting hardware, and feeder pump and start automating their operation in seconds.

The HEART is the central hub of the motorleaf system, and can connect with up to 250 pieces of equipment. motorleaf has also developed another three pieces of hardware that can connect into the system and perform other tasks. The DROPLET connects to an operation’s water reservoir and collects essential information about water, PH, and nutrient levels, as well as temperature in the reservoir, and sends that data to the HEART. The DRIPLET enables growers to automate the delivery of PH and nutrients into the water supply based on a timer or conditions on the farm. Lastly, the POWERLEAF unit can control other equipment such as air conditioners and heaters, and can be instructed by the HEART to turn them off based on timers or sensor readings from the HEART and the DROPLET.

Motorleaf has the added benefit of continuing to collect data and automate operations even if an internet connection is lost, because the HEART acts as the main controller and router, sending out a signal to anything in range — about 90 meters — using low-frequency radio.

This 99% of guaranteed uptime is just one of the things setting motorleaf apart from other indoor grow solutions on the market. It also uses industrial quality sensors and probes, both local and cloud-stored data, multiple log-in and access profiles with a view only feature, motion detection with any webcam, and machine learning algorithms.

The motorleaf system can be used in any type of indoor farming operation from greenhouses through to warehouses and at any size. IBISWorld estimates that hydroponic growing equipment purchased in stores is already valued at $645 million, and with global hydroponic produce valued at $17.7 billion by Manifest Mind, and US legal cannabis at $5.7 billion, motorleaf has plenty of potential customers.

Motorleaf receives 40,000 data points per customer per week and therefore can start predicting a crop’s needs, solving potential problems before they exist. Also, the startup plans to use its network of data and growers to connect users to each other – on an opt-in basis – to share data, plant recipes and knowledge.

Ramen Dutta, the inventor of motorleaf, started building the first prototype after trying to find a solution flexible enough to control and automate his own gardens.

Dutta graduated from McGill University with a degree in agriculture engineering. Instead of pursuing a career in agriculture, he went into IT and launched his own company, RamComputing Services, but continued to pursue his passion for agriculture by running a small indoor hobby farm.

After several months of hacking and improving his prototype and realizing that other growers in his area also wanted such a solution, he joined forces with Ally Monk, now CEO of motorleaf. Monk has a background in business and product development for technology, including roles at eFundraising.com, which was sold to Readers Digest for $27 million, OneBigPlanet, where he helped to raise $3 million in venture capital, and MemberBenefits Inc, which was acquired by Brook Ventures.

“The demands of Ramen’s IT business meant that he didn’t want to constantly go back and forth to his operation to test PH and nutrient levels, so he looked for an off-the-shelf solution that could turn his garden into a smart garden — like a ‘Nest’ for ag — and he couldn’t find anything on the market,” says Monk. “So he started hacking together what we eventually called the HUB — for Huge Ugly Box — which was giant but started to offer the solutions he wanted.” The company has since reduced the size of this box significantly in an elegant and functional design.

Local growers instantly showed interest in the system, pushing Dutta and Monk to focus full-time on the business and they won a place in the Founders Fuel accelerator program, one of Canada’s leading accelerators, where the theme was artificial intelligence. This accelerator is funded by Real Ventures, which has now invested in motorleaf.

Now the technology is market ready and without any cash spent on marketing, motorleaf has over 200 units on order from a range of customers including OEM manufacturers, supermarkets, high schools and licensed cannabis farmers. motorleaf is now raising $750k in seed funding on AgFunder to manufacture and market its technology at scale and build out the motorleaf team.

View the profile here and email motorleaf@agfunder.com to connect with the company.

Local Food is Great, But Can It Go Too Far?

One of the most interesting developments in American agriculture during the last decade has been the rise of the local food movement

Jonathan Foley

Global Environmental Scientist, Author, Wonder Junky. Executive Director, California Academy of Sciences. Our Mission: Explore, Explain & Sustain Life.

Jul 17, 2016

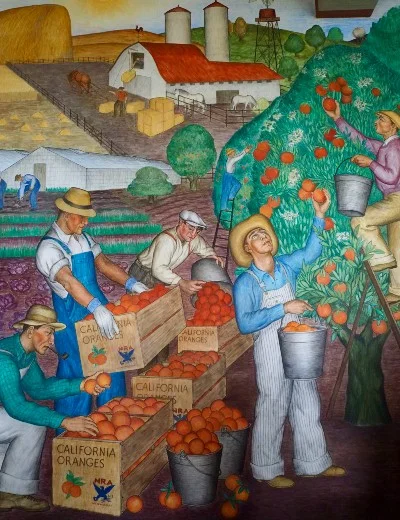

Photograph by Jonathan Foley, Copyright (c) 2014.

Local Food is Great, But Can It Go Too Far?

The local food movement has done a lot of wonderful things, especially reconnecting people with the food system. But some new efforts — which move crops indoors, inside artificially-lit, energy-intensive, high-tech containers — go too far, negating the benefits of local agriculture.

July 17, 2016 — One of the most interesting developments in American agriculture during the last decade has been the rise of the local food movement.

It’s incredibly popular. People love the idea of eating food that is grown nearby, on surrounding farms. It helps increase the sense of authenticity and integrity in our food. Also, the food can often be fresher and tastier. Many folks also like that the supply chain — the path food travels from the farmer’s field to the dinner fork — is shorter, more transparent, and supports the local economy. And who doesn’t love going to a wildly colorful farmer’s market, or a beautiful farm-to-table restaurant, and learning more about the farms, and farmers, who grew our food? No wonder local food is so popular.

Local food can also be good for the environment, especially if it reduces food waste along the supply chain. Also, many local farms are also organic or well-run conventional farms, which can produce many benefits to soils, waterways, and wildlife. And, in some places, local grass-fed ranches are trying to sequester carbon in the soil, offsetting at least part of beef’s hefty greenhouse gas emissions. Done right, local food can have many environmental benefits.

But the commonly-held belief that reducing “food miles” is always good for the environment, because they reduce the use of transportation fuel and associated CO2 emissions, turns out to be a red herring. Strange as it might seem, local food uses about the same amount of energy — per pound — to transport as long-distance food. Why? Short answer: volume and method of transport. A big box chain can ship food more efficiently — even if it travels longer distances — because of the gigantic volumes they work in. Plus, ships, trains, and even large trucks driving on Interstate highways use less fuel, per pound per mile, than small trucks driving around town.

But don’t feel bad. It turns out that “food miles” aren’t a very big source of CO2 emissions anyway, whether they’re local or not. In fact, they pale in comparison to emissions from deforestation, methane from cattle and rice fields, and nitrous oxide from over-fertilized fields. And local food systems — especially organic farms that use fewer fertilizers, and grass fed beef that sequesters carbon in the soil — can reduce these more critical emissions. At the end of the day, local food systems are generally better for the environment, including greenhouse gas emissions. Just don’t worry about emissions from food miles too much.

Without a doubt, local food has a great set of benefits. And it’s just getting started.

From Local to Super-Local

We have also seen a movement towards what you might call “super-local”food, where people grow more food right in the city. In other words: urban agriculture.

There are commercial scale urban farms popping up, like Growing Power in Milwaukee, that grow food in vacant lots and create badly needed jobs in urban neighborhoods. Others, like Gotham Greens, are growing food in rooftop greenhouses in major cities. People are also starting community gardens in their neighborhoods, where folks can share an area of land — maybe in a city park or a school yard — to grow fruits and vegetables. And, of course, many people grow super-local food at home, in their yards, or on their patios and decks. In fact, my wife and I have always grown salad greens, herbs, vegetables, and a wide range of fruits at our place — whether in a tiny yard converted to gardens and orchards in Saint Paul, or a variety of potted vegetables, herbs, and fruit trees on a deck in San Francisco. It tastes great, and there is a lot of satisfaction in doing it yourself. And I love that our daughters grew up — even as city kids — knowing a little bit about where food comes from.

But, despite these great advances, we need to remember that urban food can’t feed everyone. There’s just not enough land. In fact, the world’s agriculture takes up about 35–40% of all of the Earth’s land, a staggering sum, especially compared to cities and suburbs, which occupy less than 1% of Earth’s land. Put another way: For every acre of cities and suburbs in the world, there are about 60 acres of farms. Even the most ambitious urban farming efforts can’t replace the rest of the world’s agriculture. Fortunately, urban farmers are smart, and have focused their efforts on crops that benefit the most from being super-local, including nutritious fruits and vegetables that are best served fresh. In that way, urban food can still play a powerful role in the larger food system.

So there’s a lot to be excited about with local food. While it’s not a silver bullet solution to all of our global food problems, it’s an exciting, powerful development, and it can have important nutritional, social, economic, and environmental benefits if done well.

Some critters on my brother’s farm in Maine. Photo by Jonathan Foley, Copyright (c) 2014.

Taking It Too Far: Hyper-Local Food and Indoor “Farms”

Local food is a very welcome development. But can we take it too far?

Yes, I’m afraid we can — especially when we start to grow food indoors with energy-intensive, artificial life support systems.