Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

Growing Greens In The Spare Room As ‘Vertical Farm’ Start-Ups Flourish

Dan Albert’s farm is far from traditional. There are no picturesque, rolling fields, no tractors tilling soil; there is no white farmhouse or red barn. For that matter, there is no soil, or sunlight

Growing Greens In The Spare Room As ‘Vertical Farm’ Start-Ups Flourish

By EILENE ZIMMERMAN

JUNE 29, 2016

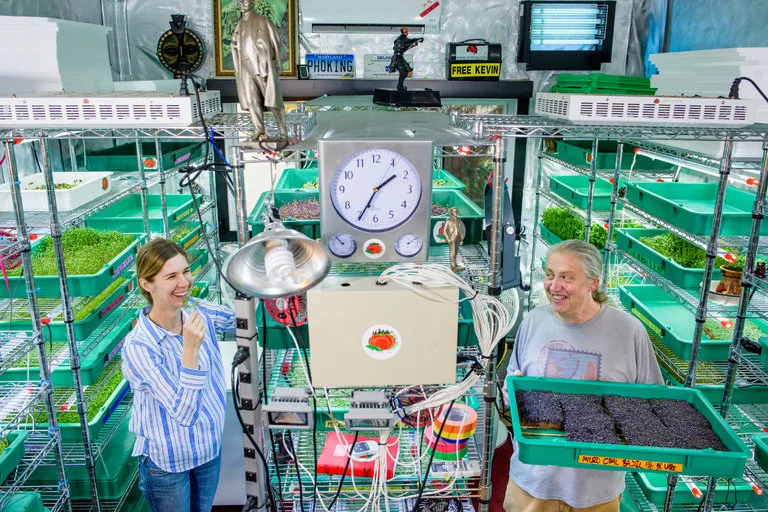

City-Hydro owners Zhanna and Larry Hountz started growing microgreens in a spare room in their Baltimore rowhouse a year and a half ago.

Dan Albert’s farm is far from traditional. There are no picturesque, rolling fields, no tractors tilling soil; there is no white farmhouse or red barn. For that matter, there is no soil, or sunlight.

The farm, Farmbox Greens, is inside a two-car garage behind Mr. Albert’s Seattle home. It consists of 600 square feet of microgreens grown in vertically stacked trays beneath LED lights.

The ability to grow in such a small space is the result of hydroponics, a system in which a plant’s roots sit in nutrient-rich water instead of soil.

Microgreens — the first, tiny greens on plants like arugula, radishes and bok choy — can go from seed to harvest in less than two weeks. That enables Farmbox Greens to compete on price against produce delivered from far away.

“We are fresher and our greens last 20 to 30 percent longer than those grown outside the area,” said Mr. Albert, who co-owns the farm with his wife, Lindsay Sidlauskas.

It has revenue of under $500,000, but was profitable enough in 2014 that Mr. Albert quit his day job as a landscape architect to farm full time. He now has three employees and sells his greens to about 50 restaurants in the Seattle area, a local grocery chain and four weekly farmers’ markets.

Consumer demand for locally grown food and the decreasing price and improved efficiency of LED lighting are driving the creation of more so-called vertical farm start-ups, said Chris Higgins, editor of Urban Ag News, which follows this segment of farming.

Energy costs are still a significant barrier to success, making few vertical farms in the United States profitable. Those that are tend to be smaller ones.

They include City-Hydro, a farm built in a spare bedroom on the second floor of Larry and Zhanna Hountz’s three-story rowhouse in Baltimore. Mr. Hountz came to urban farming out of necessity. After a serious car accident, he was unable to leave his house for two years and had trouble concentrating. He couldn’t go back to his previous job as a digital security consultant.

“Zhanna had gone to the grocery store and bought some heirloom tomatoes. They were about $7 a pound,” he said. “I thought, ‘I could grow those.’”

He converted a 10-foot-by-15-foot bedroom in their house into a vertical farm. He raises 80 different varieties of microgreens that are sold to about a dozen local restaurants.

Mr. Hountz said the farm generated about $120,000 in income, and he did not plan to expand. “We want to keep it a mom-and-pop operation,” he said.

Vertical farming uses no chemical pesticides and far less water and fertilizer than traditional farms, but energy costs can be high. Even the best LED lights have only a 50 percent efficiency rate, said Bruce Bugbee, a professor of crop physiology at Utah State University who studies controlled environment agriculture. That means half the electricity is converted to heat, not light.

“Transportation costs account for about 4 percent of the energy in the food system,” Professor Bugbee said. “The energy for electric lights is much greater than that.”

The upshot is that indoor farming can produce as much as 20 times the amount of food per unit area as conventional outdoor farming, said Gene Giacomelli, the director of the Controlled Environment Agriculture Center and a professor in agricultural and biosystems engineering at the University of Arizona in Tucson. As these farms scale up, however, they will need more electricity, not just for lighting but to run equipment like pumps and fans, Mr. Giacomelli said.

Green Spirit Farms in New Buffalo, Mich., is one operation that has found a way to be profitable on a slightly bigger scale. The farm produces leafy greens like lettuce and kale in half of a 42,000-square-foot former plastics factory.

Greens are grown hydroponically, in columns of stackable trays six levels high under “frequency-specific” induction lights. The light frequency used dictates what nutrient mix the plant gets, said Milan Kluko, Green Spirit’s co-founder and chief executive.

Green Spirit runs its system mostly on off-peak energy, from 7:01 p.m. to 6:59 a.m., when rates are 30 percent lower. The frequency-specific LED lights allowed the company to cut energy use 45 percent in the last six months, while crop yields have increased by about 40 percent.

“That’s been a huge breakthrough for us,” Mr. Kluko said. The farm’s electric bill is about $7,000 a month now, and will most likely drop to $5,000 a month by year’s end, he said.

The farm employs 11 people and produces about 5,000 pounds of mixed greens a month (7,000 pounds a month in the summer), selling to restaurants and retailers within a 100-mile radius. It has raised $1.5 million from investors and its annual sales are more than $1 million.

Such successes are prompting other vertical farming operations to grow, and grow big.

Investment in food and agriculture technology start-ups was $4.6 billion in 2015, nearly double what it was in 2014, according to AgFunder, an online investment platform for the agricultural technology industry. And local foods generated $11.7 billion in sales in 2014, which is predicted to increase to $20.2 billion by 2019, according to the consumer market research firm Packaged Facts.

Edenworks, in the Bushwick section of Brooklyn, uses an aquaponic system, which allows both plants and fish to be farmed at the same time, creating a self-regulating indoor ecosystem. Tilapia are grown in tanks and their wastewater is pumped through a bioreactor where composting bacteria turn waste into fertilizer. Plants use the fertilized water to grow and then the water is returned — minus the fertilizer — to the fish tanks.

When the cost of LED lighting decreased, the company changed the greenhouse into a vertical, indoor stacked system, using shade cloth to block light and mimic a warehouse environment, said Jason Green, a co-founder and chief executive.

Edenworks, which is not profitable, has received $1.5 million in funding and intends to build a 10,000 square-foot vertical farm in a vacant Brooklyn warehouse, which is expected to open before year’s end. Mr. Green said it should produce 130,000 pounds of leafy greens and 50,000 pounds of fish annually.

Yet profitability can be elusive for aquaponic farming. According to a 2015 Department of Agriculture study on the economics of aquaponics, raising fish indoors is two to three times as expensive as raising fish in open ponds.

Such setups are also labor-intensive, with multiple systems requiring constant monitoring, in addition to harvesting and packing. A peer-reviewed survey of commercial aquaponics operations conducted in 2013 found that fewer than one-third of farms were profitable in the previous year.

Still, Mr. Green and his competitors are optimistic about the future of vertical farming. David Rosenberg, the co-founder and chief executive of AeroFarms in Newark, said although his business was not profitable, he believed that would change when it got larger. “You really need economies of scale for this to work, to address a host of complexities,” he said.

AeroFarms plans to build large vertical farms worldwide and has raised more than $70 million to fulfill its ambitions. The company grows leafy greens aeroponically — by misting the roots with a cocktail of water, nutrients and oxygen. Mr. Rosenberg said his farm was 75 times as productive per square foot as a commercial field farm.

The company is building its next farm and global headquarters in a 70,000-square-foot former steel mill in Newark. It will be the largest indoor farm in the world, Mr. Rosenberg said.

Correction: June 29, 2016

An earlier version of the photo caption accompanying this article misspelled the surname of the owners of City-Hydro. As the article correctly notes, they are Zhanna and Larry Hountz, not Hount.

SoCal University’s Aeroponic Garden Challenges Food System Status Quo

A new teaching garden at the University of Southern California uses aeroponics to grows its fruits, vegetables and herbs

SoCal University’s Aeroponic Garden Challenges Food System Status Quo

June 28, 2016 | AJ Hughes

A prominent university in Southern California is utilizing aeroponics to challenge the food systems status quo on campus. The University of Southern California (USC) Teaching Garden was established this spring to supply fresh produce to the university’s on-campus restaurants, dining halls, catering services, and hotel, while also teaching students and staff about flavor and sustainability.

The garden utilizes aeroponic towers to produce chemical-free fruit, vegetables, herbs, and edible flowers without traditional soil growing media. Instead, plant roots are sprayed with nutrient-rich water at regular intervals to provide nourishment. The aeroponic towers at USC’s facility come from LA Urban Farms, which utilizes patentedTower Garden technology.

Each aeroponic tower is made with food-grade plastic, has room for a nutrient-rich mineral solution at its base, and holds up to 44 plants. Using this method, the project is able to raise more than 2,640 plants in just 1,200 square feet with 90 percent less water than a conventional produce operation, a boon for a drought-prone megalopolis like Los Angeles. And since growing takes place vertically, land use is kept to a minimum.

USC is the first university in the United States to utilize an aeroponic garden of this scale.

The project was spearhead by the university’s Executive Chef, Eric Ernest.

“This is a space we are co-creating together to help people understand food and food systems,” Ernest says. “We teach chefs about biodiversity and about how things are grown for different flavor experiences.”

Of course, the aeroponically-grown produce is also meant for consumption. The garden currently produces heirloom lettuces, watercress, arugula, mustard greens, kale, tomatoes, Swiss chard, snap peas, several varieties of peppers, and more, all from organic seed. Some of the microgreens are delivered in living form on grow-tables for use by chefs.

“Produce from this garden is grown by chefs for chefs,” Ernest says. “It starts a conversation and creates collaboration, and defines super-premium quality.”

Ernest says the USC Teaching Garden is a small-scale farm-to-fork effort and acknowledges that it will not make a significant direct impact on the broader food system.

“This does not change the food system on a global scale,” he says. “But we want to challenge food systems and enhance the conversation. The idea is to look for a way to challenge the status quo. Everything has to equal flavor.”

But because USC is an influential institution of higher learning, Ernest believes students who learn from and are influenced by the Teaching Garden will ultimately be the ones to foment change.

“We’re leveraging a unique portion of the university to advance lifelong food choices among students who will become decision makers,” he says.

Even though he knows food isn’t the university’s primary mission, Ernest notes that intersections exist between food and numerous other academic disciplines. This is one of the main reasons he pushed for creation of the USC Teaching Garden.

“It offers a bridge from academics to dining services,” he says. “Our goals are to use the garden to teach, cultivate knowledge, and spread this knowledge organically.”

Beyond education, the main objective of the Teaching Garden is supplying high quality produce to the university community.

“It’s all about an experience for our guests at the university and at the hotel and campus restaurants,” Ernest says. “We’re world-class chefs making world-class food. As long as we advance that agenda, everything else will fall into place.”

Grow Your Own Fresh Food In The Middle of Manhattan — Ask Henry!

Grow Your Own Fresh Food In The Middle of Manhattan — Ask Henry!

06/24/2015 02:41 pm ET | Updated Jun 24, 2016

Karin Kloosterman flux founder

It’s a natural thing for every human being to want: the ability to grow fresh, healthy food anywhere we call home, even if that’s in the concrete jungle of New York City. That’s where I’ve been spending the last couple of months as I build up my business to help people grow fresh and healthy food anywhere, even inside an apartment in Tribeca.

Yes, we may spend our days and nights plunking away at keyboards or talking into little plastic boxes but who doesn’t yearn to eat the freshest food in the world? Food that’s been grown by your own hands? This desire is multiplying. There is a shift in cities across America, and urban farming is something that’s taking root.

Young men and women are graduating college with ambitions of going on to be farmers. Horticulture schools are filling up with young people wanting to farm. They want to be a part of the Farm to Table movement. To make matters better for future urban farmers, Quartz reports that most Americans could be sustained on local foods alone, except for the cities of LA and New York.

If you are thinking even for a second about growing food on your patio, rooftop, basement, restaurant or little plot between buildings, Henry is here to help. Henry, or Henry Gordon-Smith is an urban agriculture consultant for Blue Planet. While his passion is hydroponics, or growing food on water, Henry can help you decide what, where, how and what technology you should use to maintain and enhance your urban yield.

“I like to look at the whole spectrum of urban agriculture with my clients from soil-based to hydroponics and high tech vertical farms,” Henry tells me. “Then, based on if their goals are yield, education, or job-training, our team recommends design, technology, and operations strategies.”

Will it be cucumbers, strawberries and Swiss chard? Or potatoes, lettuce and carrots? Henry is here to help. I ran into Henry at the AlleyNYC, a co-working space in New York. He graciously lends contacts, makes introductions and shares best practices on what’s happening in the city.

We know that Whole Foods in Brooklyn now operates a large (20,000 sq/ft hydroponics farm on its roof). And New Jersey’s Aerofarms is about to get something real big.

What’s next?

Formally as part of Blue Planet a company that makes nano-bubble aerators to increase hydroponic crop yield, Henry works to grow urban farms so they can be a mainstay in New York, even if you don’t use his company’s equipment.

He’s currently consulting a number of big deal projects for Sky Vegetables, an 8,000 sq/foot growing vertical farm in the city, for Coop Tech, a training rooftop greenhouse at 96 and 1st. And he’s helping develop a shipping container food art project, hopefully one that will be replicated around schools in the region.

You can say that Henry’s putting hydroponics on the map in New York City. Hydroponics or vertical farming, is a way to grow food and high value crops using water and nutrients alone - no soil. There are plenty of reasons for the planet as to why hydroponics could work as a great supplement to convention agriculture: using up to 95% less water, more vitamins, greater yield, no pesticides and the use of unconventional space are some benefits.

As for what’s hot in hydroponics in New York City, Henry plugs three projects:

1. Harlem Grown at 134 and Lennox: “With a thriving soil-based farm and a hydroponic greenhouse surrounded by buildings on three sides, this urban farm is a one-of-kind demonstration,” says Henry.

2. EdenWorks in Brooklyn, which is a data-based company working on making aquaponics feasible. Aquaponics is hydroponics with the addition of fish to provide nutrients in a closed-loop system.

3. New York Sunworks which is developing rooftop greenhouses for schools, and which plans to have 100 hydroponics food labs in the next 5 years around NYC. They’ve built 17.

If you are looking for inspiration, Henry also produces the Agritecture blog which helps people envision future hydroponics and vertical farms. He says: “It’s both utopia and real world placed side by side. My hope is that it will inspire others to be bold but also act feasibly.”

Get inside some of his inspiration by reading Dr. Dickson Despommier’s The Vertical Farm if you want to learn more about the practice and economics of hydroponics, and be in touch with Henry if you want to start an urban farm in your city.

I love how Henry is creating both a business and a business climate for hydroponics and mother earth. He’s a citizen of the world, who was born in Hong Kong, but who travels as a Canadian. A man of my own heart. He’s also super friendly.

Connect with Henry at henry@agritecture.com and join the Association for Vertical Farming to scale your vision and connect with like-minded companies in the industry.

Follow Karin Kloosterman on Twitter: www.twitter.com/karin_flux

Trendsetting Indoor Farm Would Reclaim Easton, PA Warehouse

A plan is in the works to convert an abandoned warehouse on Easton's South Side into one of the state's first commercially-sustainable indoor farms.

A plan is in the works to convert an abandoned warehouse on Easton's South Side into one of the state's first commercially-sustainable indoor farms.

The Green Works is proposed for an 80,000-square-foot warehouse at 457 W. Lincoln St., across the street from the abandoned Black Diamond warehouse, according to a letter from Bethlehem-based Taggart Associates to the Easton Area School District.

Indoor farms yield fruit, vegetables and herbs all year; keep pests and diseases away from plants; save water through recycling; and allow farmers to control light and carbon dioxide to influence how plants grow.

"The property has been considerably underutilized for many years, but the buildinghas strong potential for productive reuse," wrote Donna Taggart in the letter.

Vertical farming calls for growing plants in vertically mounted stacks, which increases crop yields compared to farms where plants are all on one level -- the ground.

The proposal is billed as Pennsylvania's first indoor urban farm on a sustainable commercial scale.

The building has the size, height and steel reinforcement that are ideal for the project, the letter says. The letter says the farm would have 30 employees. Building owner Southern Cross Management is courting tenants and building a partnership with a local university, the letter says.

Southern Cross estimates the project will cost $4.5 million.

The letter asked the school district to waive $3,380.81 in penalties for unpaid school taxes by the former property owner. Southern Cross vows to pay the $38,278 in delinquent taxes, but asked the school board to waive the penalties.

According to city and Northampton County records, a total of $96,358.66 in unpaid school, city and county real estate taxes, plus penalties and interest, have accrued on the property for the past three years.

The letter was attached to the school board agenda for Tuesday's meeting, but discussion was postponed. School district Superintendent John Reinhart said he wants the district solicitor to spend more time reviewing the proposal before the administration makes a recommendation.

Southern Cross Management President William P. Fusselbaugh wasn't available to comment on the plan but offered to speak about it in a few weeks.

Rudy Miller may be reached at rmiller@lehighvalleylive.com. Follow him on Twitter @RudyMillerLV. Find Easton area news on Facebook.

Funiture Giant IKEA Wants to Help Restaurants Build Their Own Indoor Farms

The furniture chain is getting into the sustainable farming industry, one restaurant kitchen at a time

By Gillie Houston Posted June 17, 2016

The furniture chain is getting into the sustainable farming industry, one restaurant kitchen at a time.

Swedish home furnishing giant IKEA is known for its simple, affordable furniture that populates dorm rooms and studio apartments across the country. Now, the furniture chain is hoping to get into the sustainable farming industry, one restaurant kitchen at a time.

The company—which has put further emphasis on becoming more environmentally sustainable—recently threw its support behind "The Farm," a hydroponic garden that could potentially allow them to grow the food served at their stores directly inside the IKEA restaurants. The in-store cafes—known for their Swedish meatballs, cinnamon rolls and lingonberry everything—are just one small slice of the company's $2 billion-a-year business. However, IKEA is hoping to use The Farm as a model for restaurants everywhere to take a more holistic, home-grown approach to the food supply chain.

The brand partnered with Space10, an independent "future-living lab" and exhibition space in Copenhagen, which acts as “an external innovation hub for IKEA.” According to PSFK, one Space10 employee compared the state of the environment to a sick human body, saying that the earth needs to time to rest and get healthier in order to recover from its current issues. The lab is hoping this DIY farming concept will provide some of that rest for the planet by moving gardens indoors and taking a little stress off the land. “We are looking into the potential of growing fresh, healthy food without chemicals much closer to consumption,” says Space10’s Simon Caspersen.

The Farm utilizes a variety of IKEA products in its design; The LED lights that power the hydroponic garden are from the store's Rydda/Vaxer line, and IKEA-brand shelves and plastic bins are used to house the plant life. All said, 80 percent of the supplies used in The Farm's initial model came from the company.

While The Farm is still in its early developmental states right now, in hopes to be eventually developed and tested in one of the chain’s restaurants—one day chefs, restaurateurs and home cooks across the world could be creating their own on-site gardens. A sustainably sourced food future could be just an IKEA trip away.

Will Indoor, Vertical Farming Help Us Feed The Planet — Or Hurt It?

Will Indoor, Vertical Farming Help Us Feed The Planet — Or Hurt It?

By Tamar Haspel

Columnist, Food June 17, 2016

How Can We Feed A Population That’s Growing On A Planet That Isn’t? Grow Up!

Outdoors, an acre of land can grow an acre of lettuce. Indoors, an acre of building with plants stacked floor to ceiling can grow many acres of lettuce. Which is why, in cities around the country, entrepreneurs are turning warehouses into vertical farms. They promise local produce, responsibly grown. Do they deliver?

There are big pluses to vertical farming, the most fundamental of which is its verticality. Traditional horizontal farming is limited by its two dimensions. But if you stack plants 10 or 100 high, that acre can do the work of 10 or 100 farmed acres. On top of that, the plants grow faster: You’re not limited to the hours of daily light the sun delivers, so you get even more lettuce per square foot.

Less land is a win.

Because indoor plants are fed by fertilizer either delivered through water (hydroponic) or misted directly onto dry roots (aeroponic), they get only what they need. There’s no extra, and there’s no runoff, which translates to no algae blooms in rivers, lakes and estuaries.

Less fertilizer is a win.

Then there’s less water. As that commodity is in increasingly short supply in many parts of the world, a system that can cut water use by up to 95 percent should command our attention.

Less water is a win.

Because the climate is controlled, and there’s no soil to harbor pests or disease, indoor farming requires few pesticides. Workers are exposed to fewer toxic substances, and there are no threats to honeybees or other desirable plants or animals.

Fewer chemicals is a win.

Lettuce grown indoors can also be fine-tuned nutritionally by adjusting the fertilizer, but studies comparing indoor and outdoor lettuce nutrition find little difference, so I’ll call that a wash.

Still, that’s four non-trivial wins, and they are part of the reason vertical farming seems to have captured the imagination of urban food growers and consumers.

But before you shell out for the microgreens, there are a couple of disadvantages. The first is that you’ll have to shell out a lot, and the second gets at the heart of the inevitable trade-off between planet and people: the carbon footprint.

If you farm the old-fashioned way, you take advantage of a reliable, eternal, gloriously free source of energy: the sun. Take your plants inside, and you have to provide that energy yourself.

In the world of agriculture, there are opinions about every kind of system for growing every kind of crop, so it’s refreshing that the pivotal issue of vertical farming — energy use — boils down to something more reliable: math.

There’s no getting around the fact that plants need a certain minimum amount of light. In vertical farms, that light generally is provided efficiently, but, even so, replacing the sun is an energy-intensive business. Louis Albright, director of Cornell University’s Controlled Environment Agriculture program, has run the numbers: Each kilogram of indoor lettuce has a climate cost of four kilograms of carbon dioxide. And that’s just for the lighting. Indoor farms often need humidity control, ventilation, heating, cooling or all of the above.

Let’s compare that with field-grown lettuce. Climate cost varies according to conditions, but the estimates I found indicate that indoor lettuce production has a carbon footprint some 7 to 20 times greater than that of outdoor lettuce production. Indoor lettuce is a carbon Sasquatch.

But wait! There are ways to make up some of that. Shipping lettuce (usually from California) also has a climate cost. If your lettuce is grown in a warehouse in a nearby city, you cut that way down. But transport savings aren’t even close to bridging the gap, unless your field-grown lettuce is being flown in. The carbon cost of air freight is so high that indoor farms would be a fine substitute.

We’re not done yet.

Lighting is getting more efficient, and that will help, but there are significant limits to improvement. A spokesman for Philips Lighting said the company expects that eventually its LEDs will become 10 percent more efficient, but not much more. Albright theorizes that something like 50 percent more is possible. The theoretical maximum is that all electricity flowing to the bulb is converted to light; right now, the best bulbs convert only half of it.

There’s another way to make lighting more efficient: Pump carbon dioxide into the air. Plants photosynthesize CO2, so if there’s more of it in the atmosphere, plants can grow better with the same amount of light. According to Albright, that’s another 20 percent savings.

Combine the lighting and CO2 savings, and you’re looking at something like a 40 percent efficiency improvement in the near term. Substantial, but not enough to make indoor farms climate-competitive.

For that, we need to look at the source of the energy. Not the source at the farm; even with perfect efficiency, solar panels on the roof of a warehouse can’t come anywhere near providing enough energy for stacks and stacks of plants. It’s the source at the power plant that matters.

The carbon footprint of your lettuce depends almost entirely on the carbon footprint of your electricity. If your farm is in coal country, the carbon cost is high. Natural gas, it’s lower. About a fifth of the electricity in this country is generated by nuclear plants, which have a carbon footprint close to zero, making indoor farms a clear win. And, as renewable energy sources such as solar and wind start to contribute more to the grid, the carbon cost of vertical farms will go down.

Nate Laurell thinks about that a lot. He’s the chief executive of FarmedHere, one of the nation’s largest vertical farms, growing organic basil, microgreens, arugula, kale and more in a warehouse outside Chicago. From a climate standpoint, going vertical is making a bet that renewable energy is coming. Laurell acknowledges the high carbon cost of his products today, but says that “reducing the carbon footprint of the grid is a solvable problem over time.” In the long run, he says, “electrifying agriculture” will be a climate win because the grid will go green faster than the farm.

I can see a future where the carbon cost of indoor lettuce comes down. Whether the dollar cost comes down commensurately is hard to predict. One of the problems with vertical farming is that it’s expensive. Maintaining a building, setting up hydroponic infrastructure and paying big-city rent or real estate taxes is a wallet-thinning enterprise. To date, all the vertical farms I’m familiar with grow herbs and greens, high-value crops that they sell to well-heeled urban consumers.

I asked Laurell whether that kind of farming can break out of the basil-for-rich-people model, and he said he’s confident that it can. Although his products are now priced to be competitive with other organic greens and herbs, he’s working to reduce that price point. “Our intent is to get to a point where you have cleaner food with less chemicals that gets to the grocery store within 24 hours at a price point that isn’t just for Whole Foods,” he says. He’s aiming to be competitive with conventionally grown lettuce and expects to get there within three to five years. “A high-priced organic product that’s sold to rich consumers isn’t that interesting of a business,” he says. “To me, the interesting business solves the problem of feeding people.” Laurell was unwilling to share details of his cost-cutting plan — understandable in a competitive industry — but I wish him luck.

The bottom line on vertical farms is that today, indoor lettuce has a huge climate cost, but it’s not hard to envision a world where a transformed energy grid changes that equation. For so many reasons, let’s hope that world comes soon.

Tamar Haspel writes Unearthed, a monthly commentary in pursuit of a more constructive conversation on divisive food-policy issues. She farms oysters on Cape Cod. Find out more about her at www.tamarhaspel.com.

Best Friends Find Work Together Farming - In A Storage Container

"This is a way for us to be on the cutting edge of technology"

Best friends find work together farming - in a storage container

Updated: June 10, 2016 — 3:01 AM EDT

by Terri Akman, For The Inquirer

Sure, Parth Chauhan likes providing unblemished, just-picked lettuce, kale, cilantro, and other herbs and vegetables to his South Jersey community.

And although the 25-year-old is sold on the concept - "This is a way for us to be on the cutting edge of technology," he said - starting HomeGrown Farms was just as much about satisfying his desire to work with his lifelong best friends, Raghav Garg and Zeel Patel.

Joint ventures are, after all, something the Eastern High School alums have always done well: selling candy bars and soda in middle school, hosting a dance for local high school students, and starting the Voorhees Youth Cricket League.

So, after each graduated from his respective university (George Washington, Rowan, Rutgers) and got a first job, the friends - without any farming experience - pitched in about $75,000 in personal savings and in January began growing plants hydroponically in a 320-square-foot refrigerated enclosed storage container in Pennsauken.

Now, an acre's worth of leafy herbs and vegetables are produced on metal shelves without soil, pesticides, or herbicides. Fluorescent lighting replaces sunlight, and Mother Nature's whims take a backseat to customized amounts of water and pumped-in essential nutrients. The group can tinker with their products - fortifying kale with iron, for example - and adjust type and output for individual customers. HomeGrown uses 90 percent less water and 80 percent less fertilizer than traditional farms, CEO Chauhan said, and it doesn't have to combat disease or bugs.

"We're basically a perfect summer day every single day."

So the crops stay fresh, all of HomeGrown's produce is sold within a 30-mile radius, which includes Camden. Chauhan, of Voorhees, said, "On average, most food in America will travel around 1,500 miles before it gets to your plate," and the majority of leafy greens and herbs come from Arizona, California, and Florida. The company plans to donate 10 percent to 15 percent of their harvest to food banks. These won't be leftovers; instead, the partners will grow that much additional food with the express purpose of giving it away.

"Our goal is to go from harvest to a person's plate within 48 hours," said Garg, 25, HomeGrown's CFO.

Versions of what HomeGrown is doing - vertical, urban farming - exist in Philadelphia and its suburbs:

There's South Philly's Metropolis Farms, the city's first indoor vertical farm, where hydroponic herbs and vegetables grow in nutrient-enhanced water in troughs; Herban Farms on Cheyney University's campus, where aquaponics (the marriage of raising fish and growing plants together in one integrated system) is used to grow herbs; and BrightFarms out of New York, in Bucks County, which designs, finances, builds, and operates hydroponic greenhouse farms at or near supermarkets.

In North Jersey, a 69,000-square-foot converted steel factory in Newark serves as the new headquarters of AeroFarms, which plans to harvest up to 2 million pounds per year.

HomeGrown's concept - with its charitable component - impressed judges in a George Washington University new-venture contest. Of 195 entrants from 105 teams, HomeGrown Farms took first place in its April competition, winning more than $75,000 in cash and prizes. "It was a sense of validation," Chauhan acknowledged.

"The combination of a social purpose with good economics is a winning formula," said Lex McCusker, director of student entrepreneurship at GWU. Though he expects the founding farmers to tweak their business model as they learn and grow, he sees a bright future for the business.

So far, the team has devoted most of the year to learning, getting help from the Rutgers co-op and other advisers. Their focus has been on marketing to restaurants and consumers. They donated the first few harvests, around 100 pounds of produce, through a local food bank, with the remainder going to tastings and sampling events.

"The opportunity to have year-round, fresh, seasonal, local produce is unheard of," said Patterson Watkins, who will begin buying from HomeGrown in August.

The chef manager at the University of Pennsylvania's English House Cafe has found the company's prices competitive and appreciates its willingness to grow products based on her needs. "There's quite a movement now into these ancient greens and tough-to-find herbs, salads, and vegetables. It's neat to have folks who aren't stuck to one kind of script but are happy to try out something new and see how it goes."

Brennan Foxman, owner of Wokworks in Rittenhouse, was pleased with the trial basil, kale, and salad mix HomeGrown Farms supplied this spring.

"Typically, you need to wash kale to a tremendous degree because it often carries a lot of bacteria," he said. "With hydroponic kale, you don't have to wash it because it's a closed system. So from a labor perspective and quality perspective, it's almost unmatched."

HomeGrown also is able to provide a uniformity in produce, a characteristic Foxman appreciates. Brussels sprouts, for example, should be of equal size to cook evenly in a wok. "These guys can match your restaurant supply chain," Foxman said.

Chauhan may seem an unlikely farmer, having studied international affairs, political science, and peace studies in college. But in February 2015, while researching possible business opportunities, he stumbled on an article about indoor farming in Japan. It spoke about repurposing factories after the Fukushima earthquake and nuclear disaster to create indoor herb and vegetable gardens in areas that could no longer produce vegetables in irradiated soil.

"We thought this was our opportunity - they don't have anything like this in our area," recalled Chauhan, who still retains his job consulting for ICF International, working on Hurricane Sandy recovery.

Added Garg, "The more I learned about the state of our food system and the impact it has on the environment, the more I saw not only an opportunity but the need for the way we grow our food to change. As cities grow larger, they need to work on becoming more sustainable and food-independent."

Critics of indoor farming argue the systems rely too heavily on electricity for light and temperature regulation. HomeGrown is switching to LED lights, which consume less electricity. An eventual move into a warehouse will help them solve another challenge - a lack of space that prohibits growing larger crops, such as tomatoes and squash.

The trio has since invited Chauhan's college dance-team buddy, Pranav Kaul, 21, who graduated from George Washington this spring, to join the business as chief science officer, tasked with researching food quality and nutrients.

So far, only Garg has been able to quit his day job at the Publisher Desk to devote all his energy to HomeGrown Farms. The partners hope to follow suit by the end of the summer.

Acquiring a container site in Washington is in the works, as well as a second container in Pennsauken. The partners' plan is for 10,000-square-foot warehouses to follow in the next two years, and then ultimately to spread them throughout the world.

"We can place these units anywhere and create a warehouse system in an urbanized city so local people can access fresh produce and at the same time create good jobs," Chauhan said. "We'd like to bring these hydroponic systems to Africa, parts of Mexico, and India to be able to have an impact on a global level."

Are Shipping Containers the Future of Farming?

The startup Freight Farms is using repurposed freight containers and LED lights to grow acres’ worth of produce in a fraction of the space.

The startup Freight Farms is using repurposed freight containers and LED lights to grow acres’ worth of produce in a fraction of the space.

INSIDE THE CAVERNOUS INTERIOR of a former Boston-area taxi depot—walls covered in graffiti, pools of water on the concrete floors—three gleaming green-and-white containers sit side by side. The steel boxes are former “reefers”—refrigerated shipping containers used to transport cold goods. Bone-chilling rain is falling outside, but inside the 320-square-foot boxes, it’s a relatively balmy 63 degrees, and the humid air is heavy with the earthy smell of greens. Filling each box are 256 neat vertical towers of plants, bathed in a noonday-intense pink light.

The crops being cultivated here—lettuce, herbs and other leafy greens—are not what we’ve come to expect from this kind of operation. But the company behind this agricultural innovation owes a large debt to America’s pot farmers. Freight Farms was founded in 2010, its existence predicated on a bet that LEDs would soon become efficient enough for farming as if the sun had disappeared—without breaking the bank. Co-founder Brad McNamara puts it this way: “Traditional research said, yeah, LEDs are good, but the more important research was that they were improving at a Moore’s-Law rate.” Moore’s Law, used to describe the exponential increase in computing power over the past 50 years, can be applied to LEDs thanks in part to the needs—and considerable resources—of marijuana growers.

Companies like Green Line Growers in South Boston are farming year-round in refrigerated shipping containers developed by Freight Farms. Video: Gabe Johnson/WSJ. Photo: Tony Luong for The Wall Street Journal PHOTO: TONY LUONG FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

In addition to 128 LED strips, each “farm” has a water circulation system, 8 gallon-size tanks of liquid fertilizer and a propane tank for producing supplemental CO2—all running on as little as 10 gallons of water and 80 kWh of energy per day. Under the right conditions, a grower can go from seeds to sellable produce within six weeks. According to data pooled by the company, an average Freight Farms box can produce 48,568 marketable mini-heads of lettuce a year—the growing power of two acres of farmland.

Freight Farms is part of a rapidly expanding field: Food and agricultural technology startups received $4.6 billion in investment in 2015, almost double the $2.36 billion that poured into the sector in 2014, according to a report from agriculture investment platform AgFunder. Companies like John Deere and Monsanto have long invested in new technology for conventional farming, but we’re now seeing a disruption of farming itself.

In 2010, Gotham Greens completed what was then the world’s largest rooftop greenhouse, perched atop a Brooklyn warehouse. “When we started this thing in 2009, we were one of the only ones out of this new guard of hydroponic indoor farming,” says co-founder and CEO Viraj Puri. “In 2016, there’s probably 100 of us.” Near Chicago, FarmedHere, which sells produce to Whole Foods, operates a 16,000-square-foot warehouse filled with towers of hydroponic greenery. In Newark, N.J., AeroFarms, which recently received over $30 million from investors such as Goldman Sachs, is transforming a 70,000-square-foot steel mill into the world’s largest indoor vertical farm.

Freight Farms has received $5 million in funding to date and projects to sell 150 farms this year, at $80,000 each. Selling produce to consumers has proved difficult for many ag startups, but Freight Farms operates no commercial farms itself; instead, the company supplies the technological infrastructure and tools to grow. As a result, its business model has less in common with agricultural operations than it does with Google or Facebook, from its start in a tech incubator to its reliance on data, code and automation. Every Freight Farms box sends a river of data—such as temperature, humidity readings and CO2 levels—back to the company’s central servers. Just as Google becomes more powerful as more people use it, each Freight Farms owner benefits from insight gained across the network. Buyers, many of whom are first-time farmers, are trained in a two-day course and connected by a private online forum where they share everything from data on crop selection to marketing ideas.

There are more than 60 Freight Farms containers installed in 22 states and two Canadian provinces, in climates ranging from the long winters of Ontario to the sweltering heat of Texas. In a development that surprised even the company’s founders, the containers are increasingly making their way onto traditional farms for supplemental income outside the growing season. But most are parked in the interstitial spaces of cities, from warehouses and underneath highway overpasses to alleyways behind the restaurants where their crops are served. The result is hyperlocal produce, which sometimes travels just a few feet from farm to table.

A box farm in use. PHOTO: TONY LUONG FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

“We harvest it in the morning, and often it’s in a salad for lunch,” says Bobby Zuker, co-owner of Green Line Growers, which operates out of the former Boston-area taxi depot.

“It feels like a little bit of a science project,” says Mike Betts, a personal chef in Boston who buys lettuce, spinach, kale and herbs from Green Line Growers. “They’re specifically dialing in the nutrients—exactly what that plant needs—and it comes through. You break off their lettuce and it has heightened sweetness. Their arugula is a lot spicier than the wholesale version of it that’s cut a week before and sitting in a plastic container until I buy it.”

That just-picked freshness comes at a price. Green Line Growers sells its mini-lettuces for $1.25 a head—more than twice the cost of typical organic store-bought lettuce. Like many tech services before it, Freight Farms is starting off as a niche product for the rich, but that may not always be the case. The cost of growing indoors is likely to drop with improvements in the efficiency of LEDs, which are projected to require half as much energy in 2030 as they do today.

LED strips effect photosynthesis. PHOTO: TONY LUONG FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

Gotham Greens CEO Mr. Puri cautions that indoor farming is unlikely to render traditional farming obsolete. “Hydroponics and controlled-environment agriculture lends itself to certain types of produce, like highly perishable leafy greens, salads, herbs and vining crops like tomatoes, cucumbers and peppers,” he says “But a lot of other ag staples can’t be grown in a commercially profitable way, like grains, root vegetables and tropical fruit.” For the fortunes of Freight Farms and its competitors—not to mention American consumers on the whole—that may not matter. According to the U.S. Agriculture Department, the market for organic produce in the U.S. was $15 billion in 2014. Right now, a Freight Farms container can grow six of the 10 most popular vegetables in America, and demand for those items is expected to increase if Freight Farms achieves its ultimate goal of producing vegetables without pests or pesticide for less than the wholesale cost of their conventional alternative. If that happens, boxed farming could go a long way to feeding a growing population with shrinking arable land. And assuming Uber continues its success, there’ll be plenty more abandoned taxi depots, too.

Write to Christopher Mims at christopher.mims@wsj.com

Thesis Book - The Seed: Urban Vertical Farming

Thesis Book - The Seed: Urban Vertical Farming

2016 Syracuse University School of Architecture exhibition prize-winning thesis on Urban Vertical Farming.

A Quick Guide to Growing Herbs Indoors - Hydroponically!

Hydroponically grown herbs grow quickly and have more flavor and aroma than herbs grown in soil

A Quick Guide to Growing Herbs Indoors - Hydroponically!

May 24, 2016

Posted by: Greg Hendrick

Filed under:growing, hydroponics

I've been growing herbs indoors with hydroponics for more than 10 years now. Why? Hydroponically grown herbs grow quickly and (to my taste) have more flavor and aroma than herbs grown in soil.

A few other things I've learned about growing herbs indoors via hydroponics:

- Daytime temperatures of about 65°F to 70°F are preferred by herbs, although they can withstand climbs into the 70s. It's helpful if night temperatures drop at least 10°F to simulate outdoor conditions.”

- Most herbs like to be well watered but don't like constantly wet feet ... so good drainage or exposure to oxygen is important.

- Remember that plants weakened by hot, dry indoor conditions are more susceptible to spider mites, whiteflys, or aphid damage.

Here’s a list of the 8 herbs I've found grow best with hydroponics:

Cilantro

Cilantro can be used in a variety of ways but is particularly suited to Asian and Mexican dishes. Pruning back Cilantro often will help delay bolting and prolong its harvest time. I suggest planting new seeds about every 6-8 weeks to ensure good, year around production. Health benefits of Cilantro.

Chamomile

The two most commonly found types of chamomile are the German and Roman varieties. These have been used since Ancient times for their calming and anti-inflammatory properties. Health benefits of chamomile.

Lemon Balm

Lemon Balm propagates easily and growth is rapid. Historically it has been used as a natural flavoring additive for foods, a cosmetic, an herbal tea and a highly-revered essential oil. Pick individual leaves, or bunches. If you have picked branches/bunches of them, tie them in bunches and hang them in a cool, dry location.

Marjoram

Marjoram has a milder, sweet flavor than oregano with perhaps a hint of balsam. It is said to be “the” meat herb but compliments all foods except sweets.

It thrives with full sun and grows to a compact 8 or 10 inches. Tiny white or pink clumps of flowers will form at the tips of the marjoram plant. To extend the life of the plant and encourage more leaf production, remove these buds as they form. More about majoram.

Oregano

Oregano is great in pizza, spaghetti and marinara sauces and also complements beef or lamb stews, gravies, salads, soups, and even tomato juice! It will germinate rapidly in Root cubes or Rapid Rooters when propagating. It grows exceptionally well indoors under high output T5 fluorescent plant lights in hydroponic systems. It’s an excellent companion plant for tomatoes and peppers and actually grows better when near basil. Oregano is a repellent of aphids.

Mint

Mint is well-suited for hydroponic growing and was, in fact, one of the first plants to be grown hydroponically. Mint grown in water tends to have bigger, fuller foliage than land-grown mint, and is ideal in hydroponic gardens. Mint may be transplanted using cuttings.

Harvesting is easy — simply snip leaves and sprigs as needed. To harvest larger quantities, cut stems about an inch above its growing surface.

Thyme

Thyme requires minimal fertilization when grown in a hydroponic system. It propagates well through stem cuttings and is in fact the herb which no cook should be without! It’s an aromatic and attractive plant which likes full sun and will grow poorly in minimum light. Thyme can be propagated easily using stem cuttings. Watch out for whitefly and spider mites though as Thyme s susceptible to them.

Basil

Basil is one of the most tasty and prolific herbs that may be grown and is extremely popular for hydroponic growing. Once mature, it can be harvested and trimmed weekly. It prefers a pH range between 5.5 and 6.5 so fits well other herbs. Compact cultivars of basil such as “Bush” or “Spicy Globe” make fragrant and attractive houseplants without needing a lot of room.

Watercress

Watercress is a water loving herb that can be easily grown from seed or propagated by bits of stem placed in a rooting plug or growing medium. It’s an easy cut-and-grow type of herb that’s wonderfully suited in fresh salads, soups and watercress sandwiches. Normally the thicker stems are removed and just the succulent leaves are eaten.

A few other herbs that do well hydroponically include: anise, catnip, chamomile, chervil, chives, coriander, dill, fennel, lavender, parsley, rosemary, and tarragon.

Growing Tips

Water & Nutrients for Herbs

A good quality hydroponic nutrient formulation is important. I suggest products with adequate nitrogen and a good phosphorus ratio. Most herbs prefer low to mid electrical conductivity levels (1-1.6) and total dissolvable salt levels of between 800 and 1200 ppm (measuring total salts is a way to ensure correct nutrient levels). A slightly acidic pH between 5.5 and 6.4 is ideal. Here’s a link to a list of pH, EC, and salt levels for a number of vegetables and herbs.

Lighting

T-5 high-output fluorescent fixtures with 6500K tubes are excellent choices for a hydroponic herb garden. T-5’s run cooler than metal halide lamps and can be placed usually within 6-12 inches from the plants. They use very little energy and are cost-effective.

Hydroponic Systems

The Foody 8 hydroponic tower uses a growing medium such as Hydroton clay pellets to provide good anchorage and aeration and is excellent for herbs. It may be used indoors as well as outdoors.

Foody 12 vertical garden towers (indoor use only) use a siphon system which allows water in each growing pod to automatically lower every 2 minutes to pull in fresh oxygen to the roots. This feature ensures healthy plant growth and provides a good herb growing environment.

IKEA is selling hydroponic grow kits to grow vegetables inside. Urban farmers unite!

Ikea & hydroponic grow kits!

No soil necessary. It's the hallmark of hydroponic gardening, plants held in place while their roots dangle in nourishing water.

IKEA is using is mass marketing capabilities to bring this, newly miniaturized, technology to the masses.

It is with the idea that it should be affordable to grow your own food. An aspiring gardener can suit up and get to it, even in a high-rise apartment building, for around $50.

The system is a basic grow tray with small pods to put your seeds in. Once seeded, keep an eye on the water level and make sure they get enough light. You'll have veggies soon.

One of the scientists that worked with IKEA to help create the hydroponic system is Helena Karlén, lecturer at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences. She reveals the challenge "to make growing plants in a hydroponic system simple, so that anyone could succeed," adding, "we were also very interested, not only that they grow, but also the taste... they should taste good, very good actually."

Vertically farming vegetables and living in the city just got synergistic on the cheap.

By Ian Crossland

Profits From Eco-friendly Vertical Farming Stack Up

“We look at every single major urban environment as an opportunity”

Profits From Eco-friendly Vertical Farming Stack Up

Last Updated: May 20, 2016 9:47 AM

Profits From Eco-friendly Vertical Farming Stack Up

NEWARK, NEW JERSEY —

Vertical farming — a tech-savvy subset of farming in which plants are stacked indoors, floor-to-ceiling, using controlled-environment agriculture (CEA) methods — is growing rapidly, changing the business landscape of traditional supply chains and growing seasons.

It is also having a profound effect on the environment.

Ask Newark, New Jersey-based AeroFarms, which set up shop in a neon-sprayed former paintball and laser tag arena next to a highway in the city’s Ironbound district. Its warehouse is the size of a Walmart Supercenter, but exclusively for leafy greens and herbs — more than 250 varieties.

AeroFarms aisles rise tall — accessible only by forklift crane — with shelves that are specialized growing labs using patented LED lights, aeroponic mist and reusable cloth.

To enter, farmers must suit up appropriately: gloves, lab coat, hairnet. Shoes must be disinfected.

AeroFarms’ high-yielding, economically efficient technology has made it the commercial leader in indoor farming, a market that is expected to quadruple over the next five years to nearly $4 billion.

AeroFarms co-founder and CEO David Rosenberg says the decision to focus on leafy greens was not based on any technological constraint, but rather business optimization.

“These are relatively high price-per-pound items, so it absorbs some of the price premiums with the new technology,” Rosenberg said.

95% water reduction, zero pesticides

AeroFarms’ output is consistent year-round, and it's consistently good for the environment — the effects of soil erosion, pesticides, water overuse and carbon emissions are heavily reduced, in some cases eliminated. The result is a net win for AeroFarms and the Earth.

“We could take up seed, we could grow it using 95 percent less water. In about 16 days our output per square foot is approximately 80 times per square foot over a field farmer, and we also grow using about 50 percent less fertilizers and zero pesticides, herbicides, fungicides,” Rosenberg said. “We could do this whether it is in the Sahara or a city like Newark.”

With indoor farms already in development on four continents, AeroFarms co-founder and chief marketing officer Marc Oshima says the company’s goals are to increase its production efficiency and scale operations worldwide near major distribution channels.

“We look at every single major urban environment as an opportunity,” Oshima said. “We look at things like urban density, we think about population, we think about people who are eating leafy greens.”

They also consider plants that are specific to their audience.

“We think about amaranth, one of the most popular greens in Africa and Southeast Asia. We think about how we can really bring and celebrate different types of varieties and different types of greens that are going to be specific to those regions.”

The farms also serve as tasting labs for AeroFarms' packaged varieties of supermarket-available, ready-to-eat leafy greens. Its baby watercress — labeled as “bright and crisp with a slight sweetness and a healthy dose of spice" — also happens to be an AeroFarms office favorite.

Alina Zolotareva, registered dietitian nutritionist and self-described foodie at AeroFarms, says her objective, from a public health standpoint, is to get people to eat more leafy greens like kale, one of the most nutritionally dense foods on the planet. To achieve this, producing the perfect taste is essential.

“Americans especially don't eat enough vegetables, so for me the most exciting part is all of the different flavors that we have here,” Zolotareva said. “It makes eating your vegetables so much more exciting and so much more fun.”

The farm’s specialty kale, in her opinion, “melts in your mouth.”

“A lot of people like the nutritional density of kale, but they don’t like the taste,” added Rosenberg. “So we can make a sweeter kale using the same seed, just stressing a plant to change the phytochemistry to get certain outcomes.”

6,500 square meters = 900,000-kilo harvest

Rosenberg says AeroFarms’ focus on leafy greens serves a greater function in addressing a growing food shortage worldwide. As part of a multifaceted approach to the crisis, he says consumers must shift their focus from calorie intake to nutrition.

Recent studies by the World Bank predict that an estimated global population of 9 billion in 2050 will require at least 50 percent more food. To add to the crisis, climate change is projected to cut crop yields by more than 25 percent during that span, an effect that would disproportionately affect the world’s poorest citizens.

AeroFarms, for its part, is slated to increase production significantly in the United States, in addition to its global operations. Less than a kilometer from its 2,800-square-meter farm is the site of its new global headquarters, a 6,500-square-meter former steel mill — the largest indoor vertical farm worldwide based on annual growing capacity, with a harvest rate of up to 900,000 kilos.

Vertical Greenhouse Company Expands In Canada

There is a huge amount of activity in indoor farming worldwide now

By Andy Nelson May 18, 2016 | 12:16 pm EDT

A builder of vertical greenhouse growing equipment has inked a deal with a Canadian distributor.

Las Vegas-based Indoor Farms of America signed an agreement with Greenhouses Canada to supply vertical greenhouse equipment in several Canadian provinces, according to a news release.

Indoor Farms of America’s GrowTrucks line of high-yield aeroponic growing equipment is designed to fit into a variety of spaces, including existing greenhouses, warehouse farms and container farms.

Joining forces with Indoor Farms of America will allow more Canadians to have access to locally-grown produce, Jeff Scharf, Greenhouses Canada’s president, said in the release.

“Our research shows there is no other equipment available that brings the positive economics to indoor growing in our cold regions like this does.”

Indoor Farms of America provides a cost-effective alternative to other forms of greenhouse agriculture, David Martin, the company’s CEO, said in the release.

“There is a huge amount of activity in indoor farming worldwide now. The harsh reality is that many projects won’t survive due to capital costs that are simply too high related to perceived financial performance. Our equipment was specifically designed to eliminate those harsh economics, and provide real ROI in a timely manner.”

Indoor Organic Gardens of Poughkeepsie

Environmentally, Brud explained in the City of Poughkeepsie there is over one million square feet of unoccupied building space

Indoor Organic Gardens of Poughkeepsie

Brud Hodgkins, founder of Indoor Organic Gardens of Poughkeepsie, and wife Lori

I recently had the pleasure of virtually meeting the founder of Indoor Organic Gardens of Poughkeepsie, Brud Hodgkins. First, who doesn’t love his name? It’s phonetically pronounced like brother (versus brooder). Brud is no fly-by- night operator either, as he’s logged a respected 40-year career in the financial services industry and has been enticed into his new role by the hard data and much needed agricultural sustainability aspects that indoor vertical farming exposes.

An engineer by education, he’s now putting his money where his mouth is…and putting clean and nutrient-dense micro greens into the mouths of others; namely local school children and senior citizens.

It’s known that both groups do not consistently receive or wish to eat their veggies. Smoothies are the gateway. Embedding the micro greens into smoothies hidden by vanilla and honey flavors is a brilliant way to make this happen. In fact, Brud has initiated a pilot program with 300 students (and also 300 seniors) in Dutchess County, New York. Incidentally, the county provides over 3,000 breakfasts and lunches daily to students. So there’s a market to be penetrated.

Straight away, it was evident during our discussion that Brud is on a mission. He explains it under the theory of implementing a Triple Bottom Line focused on the social, environmental and economic needs of the community.

Socially, the aforementioned need for school children and seniors’ nutritional absorption as he explains can be met through not just the obvious production output of an indoor vertical farm but from a Nutrition Factory. He’s further aligned himself with Dutchess County’s new health department commissioner, Dr. Henry Kurban, a true-believer in preventative medicine with a focus on diet and exercise. No mystery here, a good diet and consistent exercise are the essence of preventative medicine!

Environmentally, Brud explained in the City of Poughkeepsie there is over one million square feet of unoccupied building space. Back in the late 90’s, I spent some time there and found Poughkeepsie was not unlike many once-vibrant towns throughout the United States, with a semi-shuttered main street and far too many people out of work. He owns the building (on Main Street!) which gives him increased freedom to focus on energy output and consumption or the BTU (British thermal unit) which he details as only an engineer can.

Beyond his evident altruism, Brud is a business man who artfully details the third component of the Triple Bottom Line goal as economic. Putting people and buildings to work is far easier said than done but the framework is there, both literally and figuratively. In fact, the county jail is within walking distance of his operation and Brud will seek to offer ex-offenders and those men and women about to be released (under a work-furlough program) the ability to work, learn and earn.

As he digs deep into operational costs and revenue analysis, scaling his operation, building out and expanding capacity, his goals are within sight. Fed by revenue streams from supplying local restaurants (whose chef’s are more than pleased to see and taste local, fresh micro greens in the dead of winter) and newly-inked contracts with produce distributors, the future for Poughkeepsie and Dutchess County are as bright as the LED’s that light the way forward.

Japanese Robot Farm Company Going Big And Looking At New Vegetables

Vertical farming is undergoing a revolution with companies emerging across the world. They are in once case even moving straight into the supermarket’s vegetable section.

May 16, 2016 @ 06:03 AM 69,756 views The Little Black Book of Billionaire Secrets

Japanese Robot Farm Company Going Big And Looking At New Vegetable

Contributor

I write about technology, science, finance and entrepreneurship

Opinions expressed by Forbes Contributors are their own.

Companies like Spread are giving Japan’s agriculture industry a serious upgrade for the 21st century. Spread shot to fame for its highly automated, vertical farming units. The company is now looking at possibilities for widening its business, as well as possibly expanding into new kinds of produce.

Vertical farming is undergoing a revolution with companies emerging across the world. They are in once case even moving straight into the supermarket’s vegetable section.

What sets Spread apart from almost all other companies in the space is its level of automation. Its concept has been hailed as one of the world’s first true robot farms.

The company is busy creating a new, large-scale vertical farm that will deliver cleaner, more efficient production of vegetables. It is set to open in 2017. Next on the menu is opening further farms across Japan, each capable of producing up to 30.000 thousand heads of lettuce a day – making for a grand total of up to 219 million heads of lettuce a year.

New plant takes form

Construction machines are being drafted in and Spread plan to begin building the new vertical farm, which has taken almost two and a half years to plan and design, later this year. Once completed, it will also house an integrated research and development center.

The total cost will be between 1.6 and 2.0 billion yen ($14 million to $18 million). Spread expects to produce between 20 thousand and 30 thousand heads of lettuce a day. With projected prices, the plant will reach ROI in 7-9 years.

The plant’s profitability is based around economy of scale and the use of technology. The plant will grow lettuce in a soil-less and sunless environment. Robots take care of much of the handling, LEDs deliver the necessary lighting and hydroponic technology delivers water.

Spread’s environment for growing vegetables is high-tech and highly automated. Credit: Spread.

“A farming plant like this requires about half the amount of human workers our existing facility for lettuce production without automation does. We grow in a highly controlled environment, and the plants themselves are mostly handled by machines and robots. This is in part done to increase efficiency. Apart from automation, we also use water saving technology and pesticide-free cultivation,” J.J. Price, Global Marketing Manager at Spread, explains.

How to Grow Hydroponic Strawberries

How to Grow Hydroponic Strawberries

by Amy Storey | May 11, 2016 | Crops & Growing Science | Link to Upstart University Article

Strawberries: Beloved by Farmer, Beloved by Consumer.

Against the odds of nature, strawberries have persisted through the centuries; this is largely due to human interference. We have bred strawberries from their tiny ancestors into the meaty red fruit that they are today. And why not?

Strawberries are one of the most beloved crops of humankind, integrated into our lives and menus in hundreds of ways. Last week I chopped up two pounds of berries for strawberry rhubarb pie, a favorite in our cool northern climate. Strawberry lemonade, scented candles, and greeting cards all boast the sweet flavor or elegant shape of the berry. And demand for strawberries is unlikely to slow down any time soon.

High demand and good margins make strawberries a great crop for Upstart Farmers. Strawberries were the first fruiting crop to live in our ZipGrow Towers back in 2009, and Upstart Farmers have found success with the fruit since. Strawberries are popular at farmers’ markets, CSAs, and restaurants, and your unique growing technique makes them even more novelty.

Interested growers can order strawberries from most big seed companies, like Burpees or Johnny’s Seeds. Dozens of different varieties are available with new varieties being bred every year. Our first ventures into strawberries made the Seascape, a day-neutral variety, our favorite. There are many different varieties on the market that we haven’t tried yet, however, so feel free to experiment. (And let us know about your experience on the Facebook Community!)

Be sure to read up on the variety you’re planting before you purchase it. Different varieties have different environmental preferences and different bearing timelines. (One variety may take a month to start bearing fruit after planting while another may need several months.) Some varieties also only bear for part of the year, even indoors. We recommend ever-bearing or day-neutral varieties for indoor growers.

We highly recommend that you grow hydroponic strawberries from rootstock rather than seed. Vegetative growth (runners) tends to be much faster that sexual reproduction (seeds), so you can cut the time from planting to production by months or years by using rootstock.

Plant strawberries at an angle to keep water off the crown.

Take some extra time to make sure that you’re planting strawberries right. Strawberries are different from other crops. They live for a long time, but they’re also susceptible to many more diseases than most of the crops (greens and herbs) that you’ll be dealing with. Crown or heart rots are a fungal disease that are especially common for strawberries.

The crown of the plant is the region where the roots become the stem. It’s important to make sure that you keep the crown out of the wet zone.

When you plant your root stock, choose the plants with thicker crowns and talk to the provider about sterilized rootstock or a recommended fungicide dunk for the rootstock. They will have a good idea of the best fungicides for the rootstock that you can use in your state and with or without certification.

Remember: ALWAYS read the label before using a pesticide. It is a legal document, and straying from instructions is unlawful!

Plant the rootstocks at an angle so that the crown of the plant is angled upward. If the plant is planted at a downward angle, then water can run down the roots and over the crown, creating crown rot problems down the road.

You’ll see a woody “stalk” or stump near the crown of the plant that looks different from the other shoots. That is the remains of the runner from which the plant grew. Try to keep the runner on the upward side of the plant as well.

If you don’t have the space to plant all of your rootstock, you can store it in a fridge or cooler (depending on the variety, most seed companies will tell you to store the rootstock at about 32º F) for a limited time.

Maintain low salt and plenty of light.

Strawberries prefer lower salt levels (an EC of 1.2-1.5 is best), long day length, and a pH range of 5.5 to 6.8. Keep the temperature in the high 60’s and as always, keep your growing facility dry.

For farmers growing a variety of crops, salt content could be an issue in their strawberry -growing efforts. While strawberries flourish in most hydroponic systems, the high EC levels required by some crops can cause depressed yield for strawberries in the same system.

Pinch back flowers for 4-6 weeks for better yield.

In a healthy system, strawberry rootstock will have new growth sprouting up in less than a week. You can start seeing flowers at about two weeks, but it’s important to pinch back the buds for 4-6 weeks to keep the plant’s resources directed towards vegetative growth. This gives the plant the ability for higher yields later on.

If flowers are allowed to develop, fruit forms and ripens in about 2 weeks. (This does vary some by variety and growing environment.)

Hand pollinate or use natural pollinators

Outdoors, producers can rely on natural pollinators like bees, flies, and birds to spread pollen from the male parts to the female parts of the strawberry plants. Indoors, growers will either have to host a hive (be sure to check with building managers and codes), or hand pollinate.

If you’re growing in an indoor facility (including many greenhouses), one option is to hand pollinate. This can be done with a paintbrush or tooth brush. Lightly disturb the center of the flowers, one after the other. This will spread pollen from flower to flower, replacing the role of the pollinating bee or fly with your own effort.

Hand pollination can take 10-30 seconds per plant. This can be time consuming on a large scale, so consider keeping bees in your indoor farm.

Happy growing!

Once your plant is mature and producing, keep it healthy by giving it the conditions it needs and managing pests and diseases. The top pests you’ll see are crown rot and mites.

If you have any questions about growing strawberries, please leave them in the comments below! We’ll answer them and then others can learn from your questions and insights on how to grow hydroponic strawberries!

Not taking advantage of Upstart University courses?

Consider Upstart University’s guided courses, which bring you down carefully structured and personalized paths to starting a farm.

How to shrink The Family Farm So It Fits In A Box

Technology won't solve all of the world's problems, but these startups are hoping it can at least help provide more people with fresh produce

By Stacey Higginbotham

MoneyWatch May 6, 2016, 5:00 AM

How to shrink The Family Farm So It Fits In A Box

The future of farming is connected, sustainable and fits in a shipping container. At least that's what several startups around the country are hoping as they pack the tools for growing crops in a box along with lights, sensors and software in shipping containers to bring a new style of farming to urban areas.

The Ritz Carlton in Naples, Florida, has one. Boston Latin High School has one. At least two are in Anchorage, Alaska.

You can see the future of farming in several places around the country. A few miles from Atlanta's airport is a cluster of 100 shipping containers where each container can produce four tons of lettuce annually. The company that put the containers there is trying to take urban farming, the Internet of things and the trend toward eating local to the next level by helping startups stuff containers with everything an aspiring farmer needs and shipping it off.

PodPonics, the Atlanta-based company, is six years old and doesn't just operate the Atlanta containers. It takes the experience it has gleaned from its Atlanta efforts and makes software for running a container farm to sell to others.

Seedlings are transplanted into an Internet-connected, climate-controlled "farm in a box" developed by Freight Farms.

Another provider, called Vertical Harvest Hydroponics, is selling shipping containers to Alaska so restaurants can grow lettuce themselves in the rugged climate, where shipping costs can make fresh greens an expensive delicacy.

Vertical Harvest Hydroponics is just one of the new farms-in-a-box startups that are popping up. Boston-based Freight Farms is also selling a 40-foot-by-8-foot farming container. It raised $3.7 million in funding in 2014, and it has scored several clients among urban farmers, school districts and even restaurateurs.

Jon Friedman, the president and co-founder, explained that the idea was to bring greens to Boston in the dead of winter. It also shortens the amount of time farmers have to spend toiling in the fields. The automation provided by the sensors and software that come in one of the company's $82,000 shipping containers is enough to let a farmer work for roughly two hours a day in each one. In comparison, to produce the equivalent crops before, he would have to spend 15 hours.

Machines handle the rest. They provide automated irrigation, the ability to assess the quality of the growing medium and regular lighting conditions to raise healthy plants. (Most pods don't use soil, and instead deliver the plants' nutrients through water.) By combining automation with software in the cloud, these containers are able to turn a novice into a capable farmer by virtue of an app.

Friedman said providing the water and electricity for the farm costs less than $20,000 a year, allowing farmers to produce about 1,000 heads of lettuce a week. Depending on location and the season, the lettuce can range from $2 to $6 a head. Friedman is capitalizing on several trends including a renewed focus from consumers on organic and local foods.

He's also trying to make farming into something cool. People can buy a Leafy Green Machine, which is the name of the container, and start a side business growing greens. Freight Farms has sold over 100 of Leafy Green Machines so far since producing the first one in 2013.

That's helping bring food production to younger generations who have been leaving traditional farms. Friedman is even thinking about developing a package for people who want to grow marijuana, although that's not a plant that grows well vertically.

It's not all hippies and people in the colder parts of the country. The Ritz-Carlton Beach Resort of Naples has a container farm on-site where it grows its own leafy greens for the hotel's restaurant.

But container farming in schools and in urban areas isn't going to solve the looming food crisis. Around the world, climate change, the economic hardships of farming and demands for natural foods have inspired another kind of farm in a box. This style of farming is just as automated, and everything you need to build a tech-heavy farm is inside the solar-powered container. The only difference is it's designed to travel to a two-acre field and monitor the crops outdoors.

Brandi DeCarli, the founding partner at Farm From A Box, which is making this solar-powered mission control for future farms, said the goal is to let farmers with smaller plots farm them more efficiently. It also widens the range of foods that a farm can produce. Right now, DeCarli hopes to ship her containers to refugee camps or communities where fresh food is hard to find and people may not be accustomed to growing their own food.

Technology won't solve all of the world's problems, but these startups are hoping it can at least help provide more people with fresh produce.

Boston’s Freight Farms Grows Greens In Shipping Containers