Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

Will Philadelphia Become The Vertical Farming Capital

Will Philly's skyscrapers be home to urban farms?

Business Apr. 30, 2016 08:47AM EST

Will Philadelphia Become the Vertical Farming Capital of the World?

With its muggy summers and freezing winters, Philadelphia isn't exactly known as an agricultural hotspot. But a resolution passed Thursday by Philadelphia City Council could put the City of Brotherly Love on the map as the next international green hub.

Will Philly's skyscrapers be home to urban farms? Vertical farms, which use height to maximize growth space in cities, have been proposed as a way to help bring jobs and local, sustainable food to city dwellers.

Local lawmakers are aiming to expand vertical and urban farming in the bustling metropolis, Philly.com reported.

"The most noble thing a human being can do is produce food for others," Councilman Al Taubenberger, who introduced the resolution, said at a news conference held at Metropolis Farms in South Philly. "Vertical farming is something very special indeed, and fits like a glove in Philadelphia."

As EcoWatch reported, Metropolis Farms is not only the first indoor hydroponic vertical farm in Philadelphia, it’s the first vegan-certified farm in the nation and the only known vertical farm to operate on the second floor of a building. By growing food locally, the farm slashes the distance food needs to travel to get to local kitchens, grocery stores and restaurants.

Vertical and urban farming can be attractive in a variety of ways compared to conventional farming. City-based farms reduce the distance between farmer to buyer, solving the problem of “food deserts,” where city dwellers have little or no access to affordable, high-quality, fresh food.

"By the year 2050 close to 80 percent of the world’s population will be living in urban centers," Emma Hansen of the Worldwatch Institute noted. "Our current farms mandate a paradigm shift to environmentally friendly and efficient urban food systems to support the population in a sustainable way."

Philadelphia already has a number of urban agriculture projects to promote sustainable local food, and more than 40 community gardens and orchards on park land.

But with vertical farms in particular, food can be produced with less water and takes up less space than traditional farming. These technologically innovative farms often feature multiple trays of plants stacked on top of each other. Instead of growing the plants in soil, a hydroponic system recirculates the water and nutrients that plants need to grow. These farms are often often lit with artificial lights to mimic the sun. Crops can be grown in skyscrapers, abandoned lots and even shipping containers.

Metropolis Farms President Jack Griffin said his farm is able to fit 13 acres' worth of food in only 1,600 square feet, according to CBS Philly.

"The opportunity is there. The buildings are there, and people looking for jobs are there," he said, according to Philly.com. He also envisions a school where people learn about vertical farming and network of "flash farms" that directly link neighborhoods, grocery stores and restaurants to fresh food.

Metropolis Farms—located “just minutes from the south Philly Italian market made famous in the Rocky movies,” as the venture points out on their website—uses artificial lighting, climate control and other patented farming techniques to grow edible plants such as lettuce basil, peppers and carrots 365 days a year. The harvest is sold to local restaurants and grocery stores like Whole Foods.

“Remember we don’t have the weather, when it snowed this April we were growing inside,” Griffin said. “We were growing food in January.”

CBS Philly reported that Griffin plans to expand into other empty warehouses across the city with the hope of becoming a world leader in vertical farming.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

Inside Europe’s Largest Urban Farm

Floating Urban Garden Coming to New York City This Summer

One of the World’s Largest Hospitality Chains to Grow Its Own Vegetables at 1,000 Hotels

Inside The High-Tech Farm Growing Kale In An Old Paintball Arena

Aeroponics is just one form of indoor farming

Inside The High-Tech Farm Growing Kale In An Old Paintball Arena

This could be part of the future of farming.

04/26/2016 02:54 pm ET | Updated Apr 29, 2016

2.4k

Alexander C. Kaufman Senior Business Editor, The Huffington Post

NEWARK, New Jersey — David Rosenberg is trying to build an agricultural empire out of an old paintball arena in a blighted urban neighborhood about 45 minutes outside Manhattan.

Needless to say, Rosenberg, the chief executive of Aerofarms, an indoor farming startup growing organic leafy greens without sunlight or soil, has his work cut out for him.

But so far, the pieces seem to be falling into place.

Though limited, the current growing operation produces enough kale, watercress, arugula and other leafy greens to feed a few restaurants and ShopRite supermarkets in the area. Next month, the 12-year-old company is set to open its new 70,000-square-foot headquarters, just two blocks away. That project, which broke ground only two months ago, is transforming a former steel mill into the world’s largest indoor vertical farm.

“Our mission is to build farms in cities all over the world,” Rosenberg recently told The Huffington Post. “We are very much building the infrastructure not to build one, two or three farms but to build 20, 30 or 50 farms.”

Indoors farming has long been touted as a way to address two major problems. The first is macro-level and lofty: How will we, the Earth’s 7.4 billion (and counting) humans, go about feeding ourselves in a changing world? The second is more immediate: How do you get fresh, healthy produce to people in urban food deserts, where diet-related conditions like diabetes and obesity run rampant?

The answers to those questions could be a gold mine. By 2050, the world’s population is projected to rise to between 9 billion and 10 billion people. Those numbers, coupled with income growth across the world, could result in more than a 70 percent increase in demand for food by that year, according to a report by the World Bank. Making matters worse, the unpredictable and increasingly extreme weather, droughts and flooding that come of climate change are expected to grow more intense in the coming decades, as greenhouse gas emissions continue to warm the planet.

In places where extreme weather, flooding and desertification threaten agriculture — think sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East and Southeast Asia — farming techniques like those used by Aerofarms could take off.

“You have to look around the world and find out whose food supply is most threatened by climate change — it’s about who really needs it, versus who could probably survive at least another 100 years without urban agriculture dominating the landscape,” said Dickson Despommier, an emeritus professor of microbiology at Columbia University who hosts a podcast on indoor farming. “For the most part, farmers are unable to move their farms when the climate changes to the point where they can no longer grow what they were growing before.”

Rosenberg said there is a “50 percent chance” the company will announce its first overseas project by the middle of next year.

To be sure, Aerofarms is no panacea. After 12 years at it, the company seems to have created a solid model for growing nutrient-rich leafy greens in urban spaces. But it’s too small-scale to grow large cash crops like soybeans, corn and wheat — all of which are among the more environmentally taxing food sources. Plus, there are apparent obstacles to growing fruits and tubers. Consider this calculation that Stan Cox, a senior scientist at the nonprofit research group the Land Institute, offered in an essay for Alternet in February:

Based on figures in a 2013 paper published by indoor plant-growth expert Toyoki Kozai of Japan’s Chiba University and on the assumption of efficient LED lighting, I estimate that plants like potato or tomato that produce a fleshy food product require about 1,200 kilowatt-hours of electricity for each kilogram of edible tissue they produce, not counting the water stored in the food.

That requirement approximates the annual electricity consumption of the average American home refrigerator — and that’s a big energy bill to produce just two and a quarter pounds of food dry matter. This kind of thing could not be scaled up very far.

Ultimately, the world’s looming agricultural crisis is going to require a patchwork of solutions. The sheer fact that they are indoors, protected from even the most volatile environments, gives farming units like Aerofarms’ serious potential in the long term. But in the short term, can this method provide a better alternative to greens harvested in the so-called “salad bowl of America” — that is, in Northern California, where most of the country’s arugula, kale and lettuce is grown?

Pared down to its bare essentials, Aerofarms operates on a straightforward aeroponic design, using mist and carefully regulated LED lighting to grow plants without soil or another substrate. Seeds are sown into reusable growing cloths, each made from about 24 recycled plastic bottles, that are then stretched over tray-like frames. After the seeds germinate, the contraption is inserted into one end of a two-story growing tower, where the roots are regularly misted with water infused with microbes and other nutrients the plants would normally suck from the dirt around their roots. The plants then embark on an assembly line of photosynthesis, traveling down the rows of the growing tower over the course of two weeks. When they emerge on the other end, each tray is bursting with full-size edible greens.

But Aerofarms’ produce isn’t like the stuff that’s sold in most stores after being plucked from fields in California. (For one things, the company only grows about half a dozen different crops, at least for now.) Aerofarms’ greens are grown to emphasize specific flavors and textures. The mizuna, for instance, has a mustardy kick. Aerofarms grew it that way. The baby kale is almost nutty. There was no bitter chemical residue to clean off before eating.

“We grow without pesticides, herbicides, fungicides or GMOs — we just give the plant what it wants at the root structure,” Rosenberg said. “They don’t need nutrients at the leaves, so there’s nothing to wash off.”

With its aeroponic technology, Aerofarms is betting that perfecting the leafy green is simply a matter of nurture over nature. There’s no need to tweak the DNA or add artificial chemicals, the company says, when you can create the ideal environment to promote certain traits in the plant.

In a conference room at the paintball-arena-turned-growing-facility — where Aerofarms grows the crops sold in Newark in three towers stacked two stories high with plants — co-founder Marc Oshima pinched a few sprigs of watercress and popped them into his mouth like an hors d’oeuvre.

“At home, we eat this instead of popcorn,” the chief marketing officer said, going back for seconds.

One of the main criticisms of indoor farming is that without soil or sun, flavor suffers. Aerofarms’ fixation on taste may prove a competitive advantage as a bevy of competitors crop up around the country.

“It’s a shame that today we take the most highly nutritious category — leafy greens — and we supplement it with a lot of really fatty foods like salad dressing,” Rosenberg said. “Part of what we want to bring to society, and bring awareness of, is these greens in and of themselves. They’re not just nutritious. They’re all harbingers of taste.”

Anyone who’s heard a seller at a farmers market or country fair talk about their crops should recognize the affection with which Rosenberg and Oshima tout theirs. But they’re just as much tech executives as they are farmers. Rosenberg started Aerofarms in 2004 after spending years working to reduce water waste with the architect and environmentalist William McDonough, a gig that made Rosenberg a regular in posh do-gooder circles like those at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland.

Aerofarms purports to use 95 percent less water than traditional farms, and says it gets 75 times more crops per square foot of growing space than traditional field systems. To achieve that, the company has had to think of itself as a technology company as much as a farming firm.

“We’re spending big money on IT and our IT systems,” Rosenberg said. “We’re really calling it the heartbeat of the organization, in how it really touches on everything and pulls all the different pieces of the company together.”

Each of the three towers in the Newark facility is equipped with a circuit board, where sensors collect data and beam it back to the company’s servers.

“We had several ‘aha moments’ when we became Aerofarms — one of them was that, to be great on technology, we needed to be great on data,” Rosenberg said. “For a while, the company was selling farm equipment. But to be great on tech, you need good data. To get uncorrupted data, we needed to be the farmer. To be great at farming, we needed to be a leader in the technology space, because the industry is so new.”

CORRECTION: This article originally misstated that Aerofarms yields 75 percent more than crops per square foot compared to field farming. It is 75 times more.

Philadelphia Aims To Become International Hub For Indoor Farming

April 28, 2016 By Stephanie Stahl

By Stephanie Stahl

PHILADELPHIA (CBS) — On the CBS3 health watch, its vertical farming. Philadelphia aims to become an international hub for indoor growing, according to a resolution passed today by city council.

When growing produce we usually think of acres of farmland. Some say the next generation of farming will be in urban centers like Philadelphia, and you won’t need soil or the sun, just an old warehouse.

Welcome to vertical farming, where produce is grown inside, in specialized shelves that are stacked up vertically.

“We’re able to grow more food in less space,” said Jack Griffen “ we fit 13 acres in 1600 square feet.”

Inside this nondescript warehouse in South Philly is the prototype farm of the future.

“It’s a cool thing, I mean you know think about how many empty warehouses are in the Philadelphia region that could be creating jobs, that could be creating food for our local population,” said Jack Griffin the president of Metropolis Farms.

Philadelphia city council recognized Metropolis with resolutions to make the city an international hub for vertical farming.

The idea is “to establish Philadelphia as a promenade training center for this type of farming,” said Al Taubenberger.

“Remember we don’t have the weather, when it snowed this April we were growing inside,” Jack said. “We were growing food in January.”

The year round inside farm works by using artificial light. The light and the plants are grown in nutrient rich water, that’s constantly recycled.

“It’s the same nutrients as soil just in a cleaner fashion,” Jack said. “We’re vegan certified which means we have no pesticides, and I mean zero, no herbicides, and no manure, manure being one of the number one causes of food poisoning.”

They can grow everything from lettuce, and basil, to peppers and carrots.

“That’s about as fresh as it’s ever going to get.”

Jack has plans to branch out into empty warehouses all over the city, with hopes of becoming a world leader in vertical farming.

He says he’s addressed a variety of criticisms about vertical farming, by creating systems that are cost effective and use less electricity. Jack sells the produce to local restaurants and places like Whole Foods.

For more information, visit http://www.metropolisfarmsusa.com

Stephanie Stahl

Filed Under: HealthWatch, Stephanie Stahl, vertical farming

Oak Cliff Students Use Vertical Farming Lesson To Help Community

Students from Zumwalt Middle School are learning aquaponics, due in part to Oak Cliff being a "food desert"

Oak Cliff Students Use Vertical Farming Lesson To Help Community

Students from Zumwalt Middle School are learning aquaponics, due in part to Oak Cliff being a "food desert." Demond Fernandez reports.

Demond Fernandez, WFAA 9:16 PM. CDT April 21, 2016

DALLAS – Plants and students can make a winning combination. That is the case, at least, at Dallas Independent School District’s Sarah Zumwalt Middle School.

Students have been learning to grow foods from their classroom.

The students are harvesting mustard greens, kale and fruits using a unique tower garden system.

"We get to help the community out with fresh fruits and vegetables,” said eighth grader Kerrion Martin.

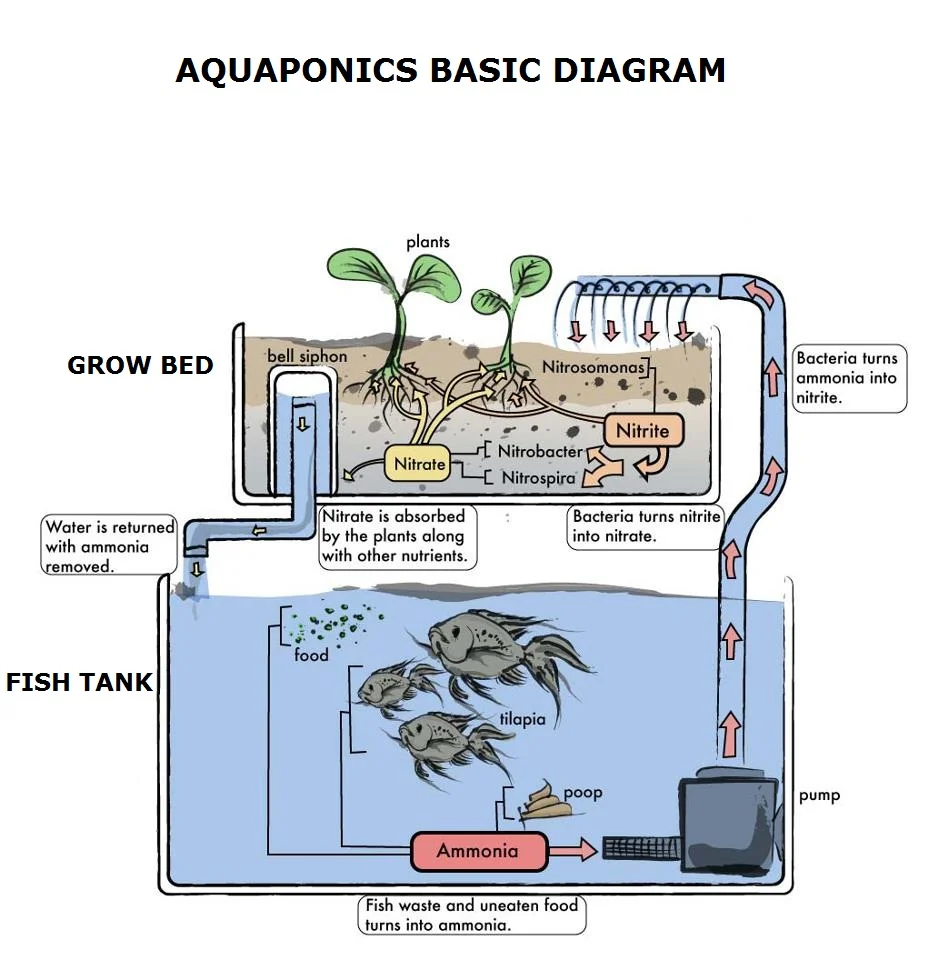

The students are have been learning about vertical farming. They are planting seeds and harvesting vegetables in a tower garden using an aquaponics system.

The class says the vertical farming project started with a provocative discussion and lesson. The students were looking into their Oak Cliff community being a food desert.

"Around here, we don't have a lot of healthy grocery stores,” Detaria Wilburn said. “We don't have a lot of healthy foods… We don't have places where they sell fresh foods, fresh fruits, vegetables."

Wilburn and her classmates are now becoming game changers with green thumbs. Tomatoes, sunflowers, peppers, and strawberries are becoming staples grown in the tower garden.

Alaric Overbey of Vertical Life Farms donated the tower garden to Zumwalt. The local entrepreneur says he saw an opportunity to help teach the teens farming skills and about healthy food options in an urban setting.

“We grew this right here in our school,” Wilburn said as she showed off a bag of fresh salad mix. “So, it’s pretty amazing.”

Each day, the students check on their plants. Every two weeks they are bagging salads for teachers to sample.

Students say the project is helping them change their own eating habits while helping others.

Copyright 2016 WFAA

Wind-Powered Vertical Skyfarms Look To A More Sustainable Future For Farming

What if the future of farming took root in the city rather than in the countryside?

What if the future of farming took root in the city rather than in the countryside? London firm Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners explores that idea with Skyfarm, a hyperboloid tower that combines different farming techniques - from aquaponics to traditional soil-based planting methods - in a bamboo-framed vertical farm designed to produce its own clean energy. The civic project was the 2014 winner of the World Architecture Festival’s Future Projects Experimental category and was praised by the jury as a “thorough, believable, and beautiful project.

- Inspired by the 2015 Milan Expo theme “feed the world,” Skyfarm was developed to help solve the global food crisis, which may be exacerbated if traditional food production fails to keep up with skyrocketing population growth. As an alternative to traditional land-intensive farming, the Skyfarm grows food vertically rather than horizontally, and can be integrated into high-density urban environments. The multi-story tensegrity structure would be made with a light bamboo frame optimized for solar exposure and efficient water distribution.

The scalable and adaptable structure’s upper levels support different kinds of agriculture including aquaponics, which produce crops and fish in a near closed-loop system. The base of the tower can be converted into a market, restaurant, or learning space to educate the public about the farm. Water tanks and wind turbines top the tower. The structure can also be altered for use in different climates; in cooler climates, for example, a double skin enclosure and heating can be applied to optimize growing conditions.

“While the upfront costs of Skyfarm are higher than standard industrial scale agriculture, the ability to grow produce with a short shelf life, such as strawberries, spinach and lettuce, around the year and close to market without costly air-freighting, makes it an attractive, sustainable proposition,” wrote the architects.

This German Invention Puts An Actual Mini Farm At The End Of Your Supermarket Aisle

This German invention puts an actual mini farm at the end of your supermarket aisle

Gives a whole new meaning to 'fresh produce'.

PETER DOCKRILL

1 APR 2016

We all know that we should be including as many fresh vegetables as possible in our diets, but the fact is that the energy and environmental costs of growing and then transporting vegetables from the farm to the supermarket can stack up pretty high.

Now one German company has come up with an interesting way of tackling the problem, designing miniature farm units that are so small and self-contained, they can be installed at the end of a conventional supermarket aisle.

Kräutergarten, meaning "herb garden", is the brainchild of vertical farming startup Infarm, which is rolling out these mini farms as part of an experimental pilot with Metro Group, a German retail chain.

"Pretty much any type of greenhouse needs scale to be economic and efficient," Infarm co-founder Guy Galonska told Adele Peters at Fast Company. "In our case, the technology we developed is kind of a building-block approach, and this building block reaches efficiencies that are much higher… It works at a very small scale, just a few square metres. So it makes a lot of sense in your neighbourhood supermarket scale."

Like other vertical farm approaches we've seen in the US and the UK, Infarm's systems take advantage of things like year-round production, low water usage, and pesticide-free techniques to deliver a low-cost, low-impact means of farming greens.

In the modular, configurable units, greens and herbs literally grow in one spot until they're ready for picking. Unlike other greenhouse systems, seedlings and more mature plants aren't moved around at all, meaning the boxes need to make clever use of every available millimetre of space inside.

Right now, only one of these farms is operating in a special supermarket designed for chefs and wholesale customers, but the company intends to begin mass-manufacturing units for mainstream outlets before the end of the year. Aside from the energy savings and environmental benefits of cutting out veggie transport from farms to where they're sold, Infarm says it also makes for a revitalised way of looking at the food you buy.

"We got many interesting responses from chefs who saw vegetables they know – because they use them every day – but they'd never seen the plants at 15 days old," says Galonska. "It really engages people. You're used to having kind of a boring experience in the grocery store. You come and get your things. Here you see a farm – it's a piece of farm in the supermarket."

The pilot unit is focusing on herbs and specialty greens including mizuna and wasabi mustard greens, but Infarm says the same boxes could easily grow produce such as eggplants, tomatoes, and chili peppers. In conjunction with an app that lets customers order the vegetables they want to buy, it's a pretty unique alternative to perusing the stock on offer down at your local grocer.

"We call this farming as a service," says Galonska. "It's similar to the software world… where we sell the technology at relatively low prices, and then provide all the supplies and additional services, like the software, for example."

Infarm hopes all kinds of supermarkets will look at installing the mini farms, and if the idea takes off, it could help transform the assumption that vertical farming and other approaches to urban agriculture aren't a robust alternative to today's high-yield but high-impact agricultural practices.

"[I]f you look forward five, 10 years from now, you see the rate of technology that is expanding, evolving. We definitely see how vertical farming can supply many other things such as rice, soybeans, certain types of fruits," says Galonska. "Will it replace completely all traditional agriculture? It will take some time. But Mars, for example, will be vertical farming only."

This German Supermarket Grows Its Own Produce

In the future, a trip to your local farm could be as simple as visiting your local grocery store

This German Supermarket Grows Its Own Produce

Tiffany DoMarch 24, 2016

You could soon be picking your lettuce straight from the source, thanks to Infarm.

In the future, a trip to your local farm could be as simple as visiting your local grocery store. This is already a reality at the Metro Supermarket in Berlin, according to Fast Co.Exist.

The Infarm, a miniature greenhouse, makes vertical farming and fresh produce accessible to the public by allowing shoppers to grab vegetables straight from the source. With this sustainable and environmentally friendly technology, transportation, storage and refrigeration are no longer factors in getting produce to the people.

The vegetables live their entire growth cycle within the glowing greenhouse, from seeds to harvest. A popular supermarket among Berlin chefs, Metro was a prime choice for Infarm, allowing shoppers to experience urban vertical farming.

“We got many interesting responses from chefs who saw vegetables they know — because they use them every day — but they’d never seen the plants at 15 days old,” Infarm cofounder Guy Galonksa told Co.Exist. “This opens up new ideas for chefs. They really see the benefits of having a burger-sized [head of] lettuce and not a really big one.”

The pilot installation, which has been running for six months and is slated to continue through the year, is currently growing herbs and greens like wasabi mustard greens and mizuna, but Co.Exist reports that the farm can be adjusted to grow anything including chilies, eggplants and tomatoes.

Study Finds Philips LED Lights Provide Improved Energy Efficiency and Production for Growing Food Crops in Space

Philips LED Lights & Production for Growing Food Crops in Space?

SOMERSET, N.J.--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Philips Lighting, a Royal Philips (NYSE: PHG, AEX, PHIA) company and global leader in lighting, has collaborated with The University of Arizona Controlled Environment Agriculture Center (CEAC) to test energy efficient ways to grow food that will help feed astronauts on missions to the moon, Mars and beyond. A recent study, conducted over a nine week period, found that replacing water-cooled high-pressure sodium (HPS) systems with energy efficient LED lighting from Philips in a prototype lunar greenhouse resulted in an increased amount of high-quality, edible lettuce while dramatically improving operational efficiency and use of resources. Lettuce grown under Philips LED modules achieved up to 54 grams/kWh of fresh weight, edible lettuce compared to lettuce grown under a high pressure sodium system which achieved only 24 grams/kWh of fresh weight, edible lettuce. This represents an energy savings of 56 percent.

“The lunar greenhouses equipped with Philips LED modules provided the light needed to produce the same amount of indoor crops that the specialized water-cooled sodium systems provide while significantly decreasing the amount of electrical energy used,” said Gene Giacomelli, Ph.D and CEAC Director. “Findings from this study are critical in that not only can it be applied to growing food in space but can be applied to farming techniques in places where there is a shortage of water and good agricultural land right here on this planet.”

Philips GreenPower LED toplighting was installed and programmed with a customized “light recipe” developed by plant specialists at Philips to optimize the results. Light recipes are formulated by taking into account a variety of factors including light spectrum, intensity, uniformity and relative position of the lamp to plant canopy. These are combined to develop specific plant characteristics such as compactness, color intensity and branch development.

In addition, the LED modules, which create less concentrated heat loads than HPS lamps, even without water cooling, can be placed closer to the plants resulting in uniform light distribution throughout the greenhouse. This ensures all plants receive the same level and quality of light, resulting in better, more uniform plant quality and a more predictable yield. The Philips LED systems also cool independently, which means no additional investment is required in cooling water distribution.

“Dr. Giacomelli and his team at CEAC have been on the cutting edge of pioneering research that is uncovering new ways to grow crops in closed and controlled environments. Results from this study will not only impact growing crops in space but will provide tangible sustainability benefits for indoor farming on our own planet,” commented Blake Lange, Business Development Manager of the Philips City Farming Division. “We know that it is becoming more difficult for traditional farming practices to keep up with the demand for high-quality, locally grown food, particularly in areas of high population density and with local water shortages. The work we are doing is focused on driving innovation of new farming technologies that allow food crops to grow in indoor environments, absent of natural light and in close proximity of cities and major population centers, thus reducing the distance from farm to fork.”

“NASA has been working with universities for over 25 years to discover how the use of LEDs can support plant growth in closed environments. Over that time we have used patented LED technology as part of the Astroculture plant growth chambers for the Space Shuttle and the International Space Station (ISS), NASA’s ground based Habitat Demonstration Unit, as well as NASA’s VEGGIE plant unit on the ISS,” said Ray Wheeler, a NASA plant physiologist. “It is fascinating to see how LED plant lighting has expanded so rapidly around the world and continues to further develop as we have seen most recently with the Mars-Lunar Greenhouse Project at the University of Arizona.”

About the Study

The project was completed over a six month period by a team led by Dr. Gene Giacomelli within the Mars-Lunar Greenhouse created by Sadler Machine Co. During a nine week period, four harvests of lettuce heads weighing 5 to 6 ounces were analyzed. All plant production and growing practices remained constant between two distinct growing systems—LEDs with the specially developed light recipes from Philips Lighting versus a traditional high pressure sodium system, which included a glass water jacket for removing the concentrated heat from the lamp bulb.

About the University of Arizona CEAC

The University of Arizona Controlled Environment Agriculture Center located in Tucson, Arizona is focused on the science and engineering of maximizing plant production within controlled environments. The Mars-Lunar Greenhouse project is a NASA collaboration supported by the Arizona-NASA Steckler Space Grant, which supports university research and technology development activities to achieve innovative research and expanded technology applications.

About Philips Lighting

Philips Lighting, a Royal Philips (NYSE: PHG, AEX: PHIA) company, is the global leader in lighting products, systems and services. Our understanding of how lighting positively affects people coupled with our deep technological know-how enable us to deliver digital lighting innovations that unlock new business value, deliver rich user experiences and help to improve lives. Serving professional and consumer markets, we sell more energy efficient LED lighting than any other company. We lead the industry in connected lighting systems and services, leveraging the Internet of Things to take light beyond illumination and transform homes, buildings and urban spaces. In 2015, we had sales of EUR 7.4 billion and employed 33,000 people worldwide. News from Philips Lighting is located at www.philips.com/newscenter.

Read more: http://www.digitaljournal.com/pr/2876870#ixzz4J3BuIQzP

Contacts

Philips Lighting

Melissa Kanter, 732-563-3994

melissa.kanter@philips.com

IKEA Launches Indoor Garden That Can Grow Food All Year-Round

If you’ve always wanted to grow your own veggies and herbs, but don’t have a yard where you can set up a garden, IKEA has the perfect product for you

If you’ve always wanted to grow your own veggies and herbs, but don’t have a yard where you can set up a garden, IKEA has the perfect product for you. The furniture retailer just unveiled its new KRYDDA/VÄXER hydroponic garden, which allows anyone to easily grow fresh produce at home. Check out the video: https://youtu.be/Sv9wD2HNSnA

The system allows customers to sprout and grow plants without any soil. Seeds can be sprouted using the absorbent foam plugs that come with the system, which keeps them moist without over-watering. Once the seeds have germinated, you can simply transfer the entire plug into its own pot and fill it with a scoop of water-absorbing pumice stones. These pots fit into a growing tray equipped with a solar lamp, providing year-round nourishment for the plants even in rooms without direct sunlight. (Or, if you choose to do things the old-fashioned way, you can simply place the tray in a convenient window.) The growing tray is even equipped with a built-in water sensor to help you ensure your plants are neither under- or over-watered.

IKEA claims the system is so simple that anyone — regardless of their experience with gardening — can successfully use it. While it’s not yet clear how much the set will cost, IKEA plans to launch the indoor gardening set in April. It’s worth noting that this is not the first indoor hydroponic garden to hit the market, although it may be a good option for people who aren’t exactly sure where to get started.

While the new system is a departure from IKEA’s usual catalog of items like bookshelves and tables, it’s in keeping with the company’s trend toward sustainability and away from a traditional retail business model. IKEA’s head of sustainability famously proclaimed earlier this year that the Western world had hit “peak home furnishings” and spoke about helping customers live more eco-friendly lives. Hopefully that means more products like this compact indoor garden are on the horizon.

Why Fixing Food Deserts Is About More Than Building Grocery Store

The U.S. Department of Agriculture has defined food deserts as parts of the country where it‘s hard to buy fresh fruit, vegetables, and other whole foods

Why Fixing Food Deserts Is About More Than Building Grocery Store

March 8, 2016 | Davina van Buren

The U.S. Department of Agriculture has defined food deserts as parts of the country where it‘s hard to buy fresh fruit, vegetables, and other whole foods. To be considered a food desert, at least 500 people or 33 percent of an area’s population must live further than one mile from a supermarket or large grocery store. That distance increases to 10 miles when defining a rural food desert. Food deserts are often located in impoverished and in areas with higher concentrations of minorities; though this is not always true.

That’s the textbook definition—but to fully understand where food deserts come from, it’s imperative to examine some of America’s not-so-shining moments. Among them: redlining, a practice used throughout the 20th century (that still occurs today) to limit or deny financial services to residents of minority and poor white neighborhoods; and “white flight,” the term used to describe the departure of whites from urban areas with increasing numbers of minorities.

“One feature of this disinvestment was pulling out places of food access,” explains Adam Brock, Adviser of Strategic Planning at The Growhaus, a nonprofit indoor farm in Denver’s Elyria-Swansea neighborhood. “Investors didn’t see as much economic opportunity in those neighborhoods as in wealthy neighborhoods, which led to situations where the food that was available was cheap and processed, often from fast food restaurants and corner stores.”

Fast forward to 2010. The term “food desert” has caught on in the United States, and first lady Michelle Obama’s Let’s Move! campaign is in full swing. Obama has made access to fresh food a cornerstone of her high-profile campaign against childhood obesity. She spearheaded the Healthy Food Financing Initiative, which offers grants, loans and tax incentives to grocers willing to open stores in underserved and impoverished areas.

The previous year, researchers from the Department of Agriculture presented a report to Congress that showed some poor neighborhoods have more grocery stores than wealthier ones. The researchers conducted a follow-up study in 2012 with the same results. Reports from various other agencies and research groups have also shown no correlation between availability of fresh food and individuals choosing a healthier diet.

Food deserts are complicated

What this plethora of contradictory information tells us is that the problem is much more complex than it may have initially seemed.

“It’s not just about plopping down bricks and sticks stores,” says Mari Gallagher of Mari Gallagher Research, a Chicago-based consulting firm known for its groundbreaking research on food deserts. “There is much more we need to do to help communities build a robust food system.”

Brock agrees. “Access to healthy food is about a lot more than proximity. It includes cultural and economic factors,” he explains. “You can have fresh vegetables down the street, but it if you don’t have time to cook them or prepare them, you are still going to go for the items that are cheap and processed.”

At The Growhaus, Brock embraces a more comprehensive approach to providing healthy food to Elyria-Swansea’s residents. Not only does the nonprofit grow food and sell it to their neighbors at a deep discount, but they also work with Denver Food Rescue to collect surplus food from grocery stores and restaurants, and are currently partnering with the city to institute a healthy corner store program. While volunteers sort and divide boxes of rescued food, visitors can take a cooking class where they can get familiar with fruits and vegetables they may have never even seen, never mind tasted or prepared. The Growhaus also works with schools and groups to teach people how to grow their own food, even in cramped apartments or tiny yards.

Brock says that living in a food desert can also lead to other challenges like high rates of obesity, diabetes and heart conditions, which are compounded by the fact that many underserved neighborhoods lack recreational opportunities and have poor air quality.

It’s about more than economics

“Part of the definition of a food desert is not having access to healthy food, but there’s a lot to how that is defined,” says Rebecca Lewis, a registered dietitian at HelloFresh. “It could be older people who don’t drive or people who have to take the bus. When you are talking about distance and transportation, a mile is far to carry groceries,” she emphasizes.

For people who have the money but lack sufficient transportation, meal delivery services like HelloFreshcan be a viable option to a healthier diet (albeit a less environmentally-friendly one). In addition to a lack of fresh food options, food deserts often have a higher concentration of fast food restaurants, which impacts obesity rates in these areas.

“The big error people make is saying, ‘I just want to get calories in,’” Lewis says. “They think, ‘If I get the dollar menu, I’m being a good parent, I’m keeping my kids full.’ But there’s a paradox: low-income people are also the ones at highest risk of obesity, which often causes health problems down the line.”

In addition to putting together nutrient-dense meals for its members, HelloFresh aims to get people cooking again. Each box comes with a recipe card that explains step by step how to prepare a healthy meal. In-house dieticians develop recipes, and even Naked Chef and food guru Jamie Oliver has signed on to curate one recipe a week.

“Back in the day, before the explosion of fast food and restaurants, people were stretching their dollars,” says Lewis. “They bought rice, beans, milk and other staples. Now we spend income on fast food. We’ve allowed others to prepare our food for us. It’s a gap that must be addressed when we talk about food deserts. You have to provide education about why you want to choose the vegetable over the dollar menu.”

As evidenced by the rising popularity of meal delivery services like HelloFresh, not everyone who lives in a food desert (as defined by the USDA’s definition) fits the stereotypical image of someone who lacks access to healthy food.

“As you start improving the problem, you realize there are other issues ingrained in it,” Lewis notes.

Policy matters

Obviously, education is an important part of the food desert puzzle—but policy also matters. Gallagher points out several problematic issues with SNAP (the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) system, formerly known as food stamps.

“One thing we see is that gas stations are growing at a rapid rate regarding participation in SNAP program, which is supposed to be the first line of defense against malnutrition. One problem with SNAP is that standards are too low, and many retailers don’t even follow those low standards. Many are not in compliance,” she explains. “When you look at who was in SNAP in 2006, and who is in SNAP in 2016, you see some of the biggest spikes are gas stations and second-day bakeries [that sell snack cakes]. That’s a bit of a policy concern. SNAP money needs to be funneled through food providers that offer nutritious foods.”

Perhaps most importantly, Gallagher strongly recommends growing local food economies.

“Instead of trucking in food to a grocery store—whether rural or urban—let’s implement a food system where more food can be produced locally,” she advocates. “Food gives us the nutrients we need, but we should also have our food system be more of a job generator. We all eat to live, but if we don’t eat well, over time, we might not live that well.”

How Vertical Farming Is Revolutionising The Way We Grow Food

Traditional farming is taking a huge toll on the environment...

Gizmodo Australia 3/05/2016

Traditional farming is taking a huge toll on the environment -- a problem that's set to worsen due to our ever-growing global population. Yet there are some high-tech solutions. Here's what you need to know about the burgeoning practice of controlled-environment agriculture and how it's set to change everything from the foods we eat to the communities we live in.

As a practice, traditional farming is not going to disappear any time soon. It will be quite some time -- if ever -- before other methods completely supplant it. But it's crucial that alternatives be devised to alleviate the pressure imposed by conventional farming methods.

An Unsustainable Practice

Negative environmental effects of traditional farming include the steady decline of soil productivity, over-consumption of water (including water pollution via sediments, salts, pesticides, manures, and fertilisers), the rise of pesticide-resistant insects, dramatic loss of wetlands and wildlife habitat, reduced genetic diversity in most crops, destruction of tropical forests and other native vegetation, and elevated levels of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. And as urban sprawl continues unabated, vast swaths of productive farmland are being eliminated. Estimates place the amount of farmland lost to development since 1970 at a whopping 30 million acres.

There are economic and social concerns as well. In addition to relying on huge federal expenditures, Big Agriculture has resulted in widening disparity among farmer incomes, concentrating agribusiness into fewer hands, and limited market competition. What's more, farmers have very little control over prices, while progressively receiving smaller and smaller portions of consumer dollars. From 1987 to 1997, for example, more than 155,000 farms were lost in North America. As noted by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, this "contributes to the disintegration of rural communities and localised marketing systems."

Controlled-environment Agriculture

As a solution, an increasing number of horticulturalists and entrepreneurs are turning to controlled-environment agriculture (CEA), and the related practice of vertical farming. While not a total panacea, these high-tech farms are doing much to address many of the problems associated with conventional farming practices.

One company that's leveraging the power of CEA is IGES Canada Ltd. Headed by President and Executive Director Michel Alarcon, IGES is working to own and operate a number of CEA facilities in both populated and remote communities. The company's overriding mandate is to rebuild resilient communities and dramatically reduce CO2 emissions.

As Alarcon explained to io9, environmentally-controlled farms like the one implemented by IGES have a number of inherent advantages. Compared to conventional farms (and depending on the exact configuration and technologies used), they're around 100 times more efficient in terms of their usage of space, 70-90% less reliant on water, with a lower CO2 footprint. Foods are grown without the use of pesticides, they're nutrient-rich, and free from chemical contaminants. And because they can be built virtually anywhere, CEAs can serve communities where certain foods aren't normally grown.

Alarcon plans to introduce his company's technology to northern regions of Canada, where they would serve aboriginal populations. Conceivably, such facilities could be installed in any number of extreme environments, including the desert or in regions stricken by drought.

These facilities, which are used by IGES to produce broad leaf products like micro-greens, herbs, and soft fruit, can produce 912 metric tons per year in a 10,000 square meter space. And that's via horizontal farming, IGES's preferred method of CEA. With increased roll-out of these facilities, the company can supplant foreign food imports during winter months.

"The savings from a reduction in transportation costs will enable the price of our food to be less than organic food prices," says Alceron.

(Credit: Goldlocki/Hochgeladen von Rasbak/CC BY-SA 3.0)

Operations like the ones visualized by IGES Canada likely will have a profound impact on local communities. CEAs will make certain foods available year-round, providing a variety of healthy food sources, while creating local employment and promoting cultural preservation.

IGES Canada will soon be initiating a crowd financing campaign, while expanding its equity financing partner base.

(Credit: Goldlocki/Hochgeladen von Rasbak/CC BY-SA 3.0)

Startup costs for ventures like these can be intense. A few years ago in Vancouver, a company sought to install a massive greenhouse for vertical lettuce production on top of a city-owned parking structure, but failed. Some of it had to do with investors and contracts with the city, but it was also hampered by high startup costs relative to the resulting crop yields. As Foodshare Senior Coordinator Katie German explained to io9, many of the farms are also set up to grow food for restaurants -- growing for high price points -- and are not necessarily concerned about making food more accessible (which the high startup costs requires). Currently, the Vancouver company is trying to sell their failed $US1.5 ($2) million greenhouse on craigslist.

AeroFarms is currently building the world’s largest vertical farm in Newark, NJ. (Credit: AeroFarms)

At the same time, there have been a number of successful implementations, including Green Sense Farms in Portage, Indiana. They're currently leasing a 30,000-square-foot warehouse in an industrial park which can serve a five-state Midwestern region. According to its CEO, Robert Colangelo, "By growing crops vertically, we are able to achieve a higher yield, with a smaller footprint."

Other successful examples include plant factories set up by the Mirai Group, and the Zero Carbon Food's operation in which a WWII bomb shelter was converted into a high-tech underground farm.

"The whole system runs automatically, with an environmental computer controlling the lighting, temperature, nutrients and air flow," noted Steven Dring, co-founder of the company, in a Bloomberg article.

Tools of the Trade

Environmentally-controlled farming is more than just a glorified form of hydroponics. These facilities employ a number of sophisticated techniques and technologies to produce nutritious and tasty foods at reasonably high yields.

Polarised Water

One critical component of the IGES model is the use of polarised water, which enables water to hold on to a greater amount of nutrients.

"The injection of energy in water modifies the bond angle of hydrogen and oxygen atoms and makes the molecular structure more attractive to nutrients, and therefore carry a higher amount of these nutrient to root and plant leaf surface and increasing growth rate," explained Alarcon.

This process also increases redox effect (oxidation) and elimination of bacterial and microbial pathogens.

CO2 Injection

Carbon dioxide (CO2) is an essential component of photosynthesis, a process also called carbon assimilation.

Photosynthesis is a chemical process that uses light energy to convert CO2 and water into sugars in green plants. These sugars are then used for growth within the plant, through respiration. The difference between the rate of photosynthesis and the rate of respiration is the basis for dry-matter accumulation, i.e. growth, in the plant.

"In greenhouse production the aim of all growers is to increase dry-matter content and economically optimise crop yield," Alarcon told io9. "CO2 increases productivity through improved plant growth and vigour."

For the majority of greenhouse crops, net photosynthesis increases as CO2 levels increase from 340 -- 1,000 ppm (parts per million). According to Alarcon, most crops show that for any given level of photosynthetically active radiation (PAR), increasing the CO2 level to 1,000 ppm will increase the photosynthesis by about 50% over ambient CO2 levels.

Ambient CO2 level in outside air is about 340 ppm by volume. All plants grow well at this level, but as CO2 levels are raised by 1,000 ppm, photosynthesis increases proportionately, resulting in more sugars and carbohydrates available for plant growth.

And CEAs provide an excellent venue for our excess CO2.

Microalgae Photobireactor

These bioreactors employ a light source and photosynthesis to cultivate phototrophic microorganisms (those that use energy from light to fuel metabolism), including plants, mosses, microalgae, cyanobacteria, and purple bacteria.

(Credit IGV Biotech/CC BY-SA 3.0)

It typically allows for much higher growth rates and purity levels than in natural habitats. Photobioreactors transform CO2 into highly nutritious plant food which is readily absorbed by plants.

Climate Control

The internal environment of CEAs must be carefully maintained, including steady temperature, humidity, and isolation from external air. Climate control minimizes plant environmental stress and exposure to harmful pests.

Lighting

Similarly, optimal multi-spectrum lighting and light exposure can be applied year-round, regardless of season and natural light availability. Recently, LED grow lights have evolved to offer multi spectrum lighting range, thus enabling a broader range of plant varieties to thrive in this environment.

Scalability

These facilities are also highly scalable. IGES Canada's operations are scalable from a 1/4 acre (250m2) operation to multiples of 3 acres (10,000m2) facilities.

Tempering Expectations

According to Timothy Hughes, an organic horticulture specialist working in Toronto, the potential social benefits to enviro-controlled farming are enormous.

"Local, dense food production spaces would provide permanent green-sector employment, as well as an excellent educational model -- providing a wider knowledge base for students and employees alike," Hughes told io9. "From one farm, you could produce vegetables, fruit, honey, fish, and textiles, for example. And by expanding the variety of crops produced, you're ensuring overall success through diversity."

At the same time, however, Hughes says that environmentally-controlled farming may be technologically flashy, but it's not as efficient as it's being touted. He points to high building maintenance and energy costs, along with ongoing technological investments.

"In terms of plant life, these systems are often reliant on technology, such as powering the hydroponics," he says. "This could be a bad thing for struggling or remote communities when reliant on these types of technology -- we're only beginning to understand these kinds of vertical farms because they haven't been built beyond traditional greenhouses."

Hughes would rather see the money spent on labour and horticultural infrastructure innovations than on enormously expensive megastructures. He points to permaculture as a possible alternative -- aquaponics in particular. Aquaponics is a system of symbiotically growing hydroponic vegetables and fish. This delivers two high-value crops while sharing resources, reducing or totally eliminating waste, and increasing energy efficiency during production.

(Credit: Johnson State College)

"I believe this maintains a scientific approach, through taking a lesson from more traditional farming -- which we know works -- and augmenting it," says Hughes. "Current greenhouses are already quite technologically advanced and have a huge amount of research put into them in terms of light technology and environmental controls. Why not build upon what we already have?"

Currently, aquaponics is in use, but not widely. Hughes envisions growing this to a larger scale, in more urban spaces, with a greater and denser mass of growing space.

"Vertical farming systems have a lot to offer, but you can further increase productivity and value through increasing biodiversity, and by doing so furthering the benefit to local communities," he says. "Biodiversity is important to the survival of all organisms, but is especially beneficial when replicating or improving a healthy growing environment. By using an Integrated Pest Management system to monitor crops and greenhouse systems, other organisms (such as pollinating and beneficial insects) can thrive in a constructed ecosystem."

And then there's the issue of soil -- or lack thereof. According to Katie German, there has been some pushback from organic farmers about not having any soil, and farming is fundamentally about soil and biology.

"If you don't have soil fertility you might be going with synthetic fertility -- which has a whole myriad of implications in regards to how it was produced and where that might negate other ways of reducing pollution," says German. She points to the work of Elliot Coleman, a veteran organic farmer who says you can't have organic food without soil.

Lastly, German says many of us are guilty of failing to acknowledge the ongoing importance of farms.

"If we talk about urban food production innovation, but lose the conversation and struggle for farmland preservation, then we are doomed," she told io9. "I think sometimes these high-tech environmentally controlled farms are sexy, but we have to make soil sexy. The UN released this report that said if we really want to feed the whole world then we need to shift to small scale organic agriculture. Which isn't sexy like growing butter lettuce in a shipping container outside of your farm-to-table restaurant."

In response to these concerns, IGES Canada says that their offering, along with those of other CEA ventures, are a complement to traditional agriculture.

"The goal isn't to grow every crop using this method, just generally the leafy greens and soft fruits," explained Patrick Hanna, IGES's Director of Marketing and Promotional Campaigns. "Cities still require farmers to provide wheat, soy, potatoes, peppers, and so on. I am of the opinion our system compliments them."

Hanna points out that some 80% of the world's arable land is currently being used by farming. And with the expected population growth, we need to find solutions to this looming issue.

"On the topic of small scale organic production, I actually agree that is the future and we intend to use this system to augment that for small scale communities, in partnership with local farmers," adds Hanna. "We see the problems created by 'Big Ag' and have developed a system to mitigate a large segment of the problems created by that unsustainable, large scale, decentralized model."

Sources:leafcertified.org|USDA

Designing the Future of Urban Farming

Helping a Berlin startup strengthen its offer of vertical farming products and services

Designing the Future of Urban Farming

Helping a Berlin startup strengthen its offer of vertical farming products and services

INFARM

The Challenge

Help INFARM develop the vision, products, and services for their B2B vertical farming offer.

The Outcome

Concepts for the industrial design of B2B vertical farm units, the interaction design of the app to control and monitor the units, and a business model for sustainability.

The challenge of how we’ll feed the exploding world population in the future—in a sustainable, cost-effective, and environmentally friendly way—is seeding an agricultural revolution in Europe.

In 2012, INFARM founders Erez, Guy Galonska, and Osnat Michaeli found that vertical farms could be a solution to urban self-sufficiency. These farms could allow people to grow vegetables and herbs in small spaces, with no soil and far less water.

If every city on earth were to grow 10 percent of its produce indoors, it would allow us to take 340,000 square miles of farmland back to forest.

Dickson Despommier, Emeritus Professor of Public Health and Microbiology at Columbia University, and father of vertical farming

An approach that’s captured the imagination of futurists for decades, vertical farming involves growing vegetables and herbs in stacked units or inclined surfaces, within which moisture, light, temperature, and nutrients are monitored, and controlled.

After creating their first vertical farming experiment in their apartment in Berlin, the founders brought together plant scientists and industrial designers to explore and develop vertical farming’s potential.

Since then, the startup has created custom growing systems for clients including Airbnb, Mercedes-Benz, and Weber. Most recently, INFARM installed a vertical farm growing herbs and vegetables at the Berlin branch of German supermarket chain Metro, the fourth-largest retail chain in the world, to sell to the public. It’s been profiled in Wired Germany, Süddeutsche Zeitung, The Guardian, and Zeit.

The vertical farm is designed to be modular, allowing consumers to purchase according to their needs.

INFARM collaborated with IDEO to further explore their B2B offer, including concepts for the industrial design of the stackable, modular, climate-controlled units; the interaction design of an accompanying app to monitor and control the units, and its business model.

Urban farmers will sign up for “farming as a service,” comprising the units themselves, as well as a monthly subscription for seeds, cartridges filled with nutrients, and a pH regulator. Because they’re stackable, the modules can be scaled to suit anyone from a home grower to a restaurant chef or supermarket owner. And Erez claims a 1 square meter growing tray can yield four to six mature plants every day, 365 days a year, doubling that of state-of-the-art hydroponic greenhouses.

The consumer app allows farmers to choose a set of herbs designed around specific recipes.

As well as remotely regulating each unit’s climate, the app will educate growers about new vegetables and herbs, selling packs of complementary seeds, with suggested recipes for them, and cooking instructions. Aiming to promote biodiversity, the firm will sell rare-breed and heirloom seeds too.

The startup has funding from the EU’s European Pioneers fund, and is now looking to secure investment to accelerate software development and ramp up their hardware production capabilities. Quite literally, it's growing its business.

MSU Leases Downtown Silos to Urban Farming Startup

"We want to see if we can redefine urban farming"

Two clusters of downtown silos owned by Missouri State University could soon be used to grow lettuce, mushrooms and other vegetables.

The governing board of MSU voted Wednesday to lease the 21 silos to a Springfield startup company, Vertical Innovations, which plans to use water-based methods to grow food.

"We want to see if we can redefine urban farming," said David Geisler, manager and general counsel for the company. "Our interest is very high. We are very much looking forward to putting a new twist on a staple in the agriculture industry in his country."

If the "vertical farming" project is successful, the company hopes to replicate the effort in other abandoned storage silos.

"They see this project as a first step, to see if their technology will work in a silo environment," said Allen Kunkel, director of MSU's Jordan Valley Innovation Center, which is adjacent to the silo clusters. "They hope to duplicate this to other properties in the Midwest that are sitting vacant."

Kunkel said the company could gain a "marketing advantage" if it's able to grow food year-round in a safe, controlled environment.

"We are excited about it," Kunkel said. "It's great to take an old agriculture facility and turn it into something new."

The 21 silos are located in the 300 block of East Phelps Street and the 400 and 500 blocks of North Boonville Avenue. There are eight silos, which stand more than 100 feet tall, adjacent to MSU's Jordan Valley Innovation Center. The other 13 silos and an elevator shaft, which exceeds 210 feet in places, are just south of the others and part of the old MFA facility.

"They are a link to our past," Geisler said. "We're just seeing if we can bring them into the 21st century."

MSU acquired the silos in the early and late 2000s, and they have largely set empty except for rotting grain. The silos include 24,650 square feet and are being leased "as is" with the understanding that the company will clean up and rehabilitate the structures.

The five-year lease agreement, which can be extended up to 35 years, will cost the company $41,950 a year. The company is expected to invest between $500,000 to $1 million to get the project started, Geisler said.

As part of the initial lease, which starts March 1 and runs through early 2021, the company is expected to clean up the silos. That cleanup will include checking for any lead paint and asbestos.

Geisler said after that, the company plans to embark on a feasibility study for its aquaponic and hydroponic methods — which include cultivating plants in water — in a silo or two.

He said the inner mechanics of the silos, which are constructed to move grain upward and downward, should help with distributing the water through the structures. If the test is successful, the project would slowly expand to the other silos.

The earliest vegetables could be produced is the fall.

"I'm pretty excited about this, not only because it's an opportunity to get those silos in better shape and looking better, but it's a real opportunity for our agricultural students to engage in this concept of urban farming," said MSU board vice chair Joe Carmichael. "It's just a real neat project."

Jim Baker, vice president for research and economic development and international programs, said agriculture students and faculty are eager to engage in the project, through hands-on learning and research.

"It's a unique opportunity to try something radically different on vertical farming, which is kind of an interesting technological challenge," Baker said. "The students are very intrigued by it.

"If this concept works, there's going to be a lot of good job creation locally and it's going to spread ... if it works."

By Claudette Riley

Is Urban Farming Only For Rich Hipsters?

Farms are springing up in cities across Europe, but if they exclude lower income groups they’ll do little to help shift towards sustainable food system

Is Urban Farming Only For Rich Hipsters?

Farms are springing up in cities across Europe, but if they exclude lower income groups they’ll do little to help shift towards sustainable food system

Gina Lovett

Monday 15 February 2016 07.35 EST

Spending on ethical food and drink products – including organic, Fairtrade, free range and freedom foods – hit £8.4bn in the UK in 2013, making up 8.5% of all household food sales.

By leveraging environmental credentials, such as local, sustainable and transparent production, a new wave of urban agriculture enterprises are justifying a premium price. But while a higher price point might better reflect the true cost of food production and help build a viable business, it can also exclude lower income groups, fuelling perception that local, sustainably produced food is the preserve of food elitists.

Making urban grown produce affordable

“This is a real challenge,” says Kate Hofman, CEO and co-founder of London-based aquaponics enterprise GrowUp Urban Farms, which produces fish, salads and herbs in unused city spaces to sell wholesale. Unit 84 – its aquaponic, vertical farm – is housed in an industrial warehouse in east London. Launched in autumn last year, it has a projected annual production of 20 tonnes of greens, salads, and herbs (enough for 200,000 salad bags) and four tonnes of tilapia (cichlid fish). It sells its produce as wholesale to local restaurants and grocers.

“Food is a commodity, and we have to make the business work. Of course, we are growing more expensive things [such as micro-greens] with a bigger margin for a customer who has more to spend, but we are trying to grow other affordable things like mixed salad, and get those into retailers that are widely accessible,” says Hofman. GrowUp Urban Farms does not share wholesale prices but, as an example, customers can currently buy 50g of peashoots through Farmdrop for £1.10 compared to £1 for the same weight on Sainsbury’s website.

As the business develops, Hofman is aiming to produce premium micro-greens for Michelin-starred restaurants that in turn can, she says, support the expansion of more affordable salads and herbs.

Accessible technology

Erez Galonska, founder and CEO of Berlin-based Infarm which sells a range of modular, app-controlled, indoor hydroponic growing systems, agrees that accessibility is important.

A big part of Infarm’s focus, according to Galonska, is democratising growing technologies to produce high quality produce at affordable prices. “Anyone [shops, restaurants, schools and hospitals] should be able to have their own farm, and grow their own food. The first ones to do it are obviously the early adopter types but, in principle, there is no reason for it not to become a standard.”

Berlin’s Metro Cash & Carry supermarket, part of the Metro Group wholesale chain, has already implemented the Infarm hydroponics system in store, growing herbs, radish and greens which Infarm says will be available at a price comparable to Metro’s other fresh goods. Infarm will begin targeting businesses globally this year.

Workforce diversity

Swiss aquaponics enterprise Urban Farmers – which sells its urban growing system and raises tilapia, micro-greens, salads and herbs – has taken over the rooftop floors of De Schilde, a former Philips TV and phone set factory in The Hague. It aims to produce 45 tonnes of vegetables and 19 tonnes of tilapia annually from summer 2016. Other enterprises including a microbrewery are expected to follow.

Tycho Vermeulen – a horticulture researcher from Wageningen University who has worked to attract more urban agriculture enterprises to become tenants of De Schilde – is concerned about diversity of the urban farming workforce. “It’s just an observation, but the tendency for urban agriculture entrepreneurs is to be white and middle-class,” he says.

Urban Farmers pilot rooftop farm in Basel , based in the Dreispitz area south of Basel, just a few tram stops from the centre of the city. Photograph: Raphi See (Raphael Seebacher)/Urban Farmers

For urban agriculture to move beyond serving a niche group of people and make a real impact on the global food system, it will have to engage a wider demographic. This has been the driver behind GrowUp’s education and training programme in the London borough of Newham.

According to Hofman, Newham has “one of London’s highest unemployment rates ... There’s a real need for job opportunities [with companies] that are prepared to invest in training young people with a poor history of educational attainment”.

GrowUp has created roles specifically for young local people with a history of poor educational attainment, training them as aquaponics technicians for commercial food production and developing their skills in planning crops and monitoring quality. Hofman hopes that they will stay and develop with the business as it expands.

Wider inequalities in the food system

For some the challenges around equality in urban agriculture are simply a reflection of the global food system’s wider issues. Patrick Holden, founding director and CEO of the Sustainable Food Trust, says, for example, that many of those working in the food sector are paid poorly and as a result, “the people who produce our food can’t afford good food”.

Holden hopes the interest in urban food will end up benefitting the whole of society in the future. “There’s a whole generation for whom urban food growing is becoming a major interest. These kinds of food revolutions tend to be led by people who have more information, and maybe more disposable income, but that’s not to say they’re not tapping into something of interest to all sections of society,” he says.

Loudoun Farm Family Is Growing In New Directions

Instead of using soil, Virts grows his plants in water, feeding them with a fertilizer solution

By Jim Barnes January 18

The Virts family has been engaged in traditional farming (think heavy equipment, rigid growing seasons and cornfields stretching for acres) since it settled in Loudoun County in the late 18th century. Twelve generations later, things are beginning to change.

Donald Virts, who farms 1,000 acres in northern and western Loudoun, decided that he had to adapt his methods to evolving economic and environmental conditions. His new business model, which he is introducing at CEA Farms north of Purcellville, embraces concepts such as hydroponics (growing crops in water), controlled environment farming, renewable energy sources and marketing directly to consumers.

Virts, 56, said his family grew traditional crops such as corn and soybeans when he was growing up, as well as raising cattle for milk and beef.

He said that for decades, he followed a similar model but that doing so increasingly became a struggle. He had trouble finding workers who were willing to put in the required hours for wages he could afford.

“If I couldn’t do it by myself, I couldn’t do it,” Virts said. “That’s not good. You can’t make a living doing everything by yourself.”

He also realized that the costs of land and equipment had grown too high and that profits were too small.

“I couldn’t keep fighting that any longer in Loudoun County,” he said. “So I had to do something.”

In fall 2014, Virts built a greenhouse on his property at Purcellville Road and Route 9. The controlled environment allows him to grow tomatoes, strawberries, lettuce, cucumbers and other produce year-round. The greenhouse increased his yield and reduced water consumption.

“The general rule is that you get 50 to 80 percent more volume per acre using 30 to 50 percent less water,” he said. By growing the plants vertically in racks, mounted one above another, Virts is able to make the best use of the space, he said.

Instead of using soil, Virts grows his plants in water, feeding them with a fertilizer solution. This eliminates the need for chemicals to kill pests and weeds, and gives him maximum control over what goes into the plants, he said.

Light, temperature, ventilation and even the pollinators can be controlled inside the greenhouse, Virts said. Every month or two, he puts in a box of bees to pollinate the plants.

CEA Farms — the name stands for controlled environment agriculture — is the most diversified hydroponics operation in the region, said Kellie Boles, Loudoun’s agricultural development officer.

“The fact that he’s growing strawberries, tomatoes, peppers and cucumbers is just extraordinary,” Boles said.

Virts decided that another way to increase his profits would be to sell his produce directly to customers. Hoping to capitalize on the growing number of tourists who are flocking to Loudoun’s wineries, he opened a farm store in the fall next to the greenhouse to sell produce from his farm.

The store also sells organically grown produce from other local suppliers, as well as beef, pork and lamb from livestock raised nearby. It houses a kitchen and an informal dining area where customers can eat freshly prepared sandwiches made from the meats and produce sold there.

“When I cook these burgers and serve them to people, as soon as they eat it, they come over and buy some [packaged meat], because of the flavor,” Virts said. “And when they put a slice of these tomatoes and a piece of lettuce on it, I’ve got a customer for life.”

Virts’s long-term plan includes adding several greenhouses and powering them from renewable sources such as water, solar energy and wind. He thinks his store will be able to handle the yield from all of the greenhouses.

“That’s the ultimate goal of what my family and I are trying to do here,” he said. “Everything we grow here on our farms, we want to market [directly] to the public.”

Barnes is a freelance writer.

Urban Cultivator And The Zero-Mile Diet

It grows your tray greens, microgreens and salad leaves either hydroponically or with soil. I am currently growing wheatgrass, sunflower greens and pea shoots hydroponically, and some baby kale salad leaves in soil

Urban Cultivator and the Zero-Mile Diet

Posted on December 29, 2015by Max Tuck

Most people would consider me to be the very opposite of an “early adopter”. Heck, I don’t even own a smartphone (or an i-pad, i-pod, or other such technology that you allegedly can’t live without in the modern world). But when it comes to equipment associated with the living foods lifestyle (of which I was very definitely an early adopter 25 years ago), I’m right there. Green Star Elite juicer – check. Excalibur dehydrator – check. Vitamix – check. Automatic sprouter – check (actually, I’ve got two). So when I heard via the Hippocrates newsletter that a new, “can’t-live-without-on-this-lifestyle” product was available, I was straight on the internet to find out if this amazing piece of Canadian kit could be obtained on my side of the pond. Enter Continental Chef Supplies (CCS), the only UK distributor of the magnificent Urban Cultivator; the machine that really could make a “zero mile diet” a realistic possibility.

So, what is it, is it all it’s cracked up to be, how does it work and will it really save time and money? Coming up, but remember back to a time perhaps a few years ago when your kitchen might have looked a bit different. How long have you had a dishwasher? I was certainly a “late adopter” of one of those, but wouldn’t be without it now. And how many people these days have a posh built-in coffee maker, or maybe, on a smaller budget, a Nutribullet, compared to 5, or even 2 years ago? What was once considered a gimmick might well become tomorrow’s essential. This was my initial feeling the moment I saw the Urban Cultivator.

In November, finding myself in London with a couple of hours to spare, I hopped on over to the CCS showroom in Baker Street. And there before my very eyes stood the latest wonder of modern technology – a Commercial Cultivator. This unit is primarily designed for chefs and professional kitchens; with four levels, and fitting 4 large growing trays onto each, it is otherwise either for someone who runs a small wheatgrass-growing business, or someone with a large raw-eating family. Try as I might, I could not think of anywhere in my kitchen that I could fit in one of these behemoths. I’d need a pretty large kitchen extension to accommodate one (or maybe 3 days on a serious garage clear-out mission – now there’s an idea!). It still might represent a relative overkill for my personal needs, but hey, I can dream.

Slightly more realistically, in another part of the showroom, stands the Residential Cultivator. The same size as an under-counter fridge or freezer, this unit does not require a major re-think of your living space. With two levels, and two large trays in each, it is ideal for a health-conscious couple who want to grow their own microgreens and tray greens such as wheatgrass, sunflower greens and pea shoots. Whilst you can certainly grow these outdoors for part of the year in the UK, depending on where you live, I have found that sunflower greens won’t grow on my outdoor, protected rack past October, and they don’t like it if I put them outside until the end of April. I therefore embraced the opportunity to have a residential unit on trial for a 3 month period – winter being the ideal time to put it through its paces. I cleared a redundant space in my utility room, cut a narrow section of worktop away and the unit was delivered on 11th December 2015, just as promised.

First impressions